This is an original research article. To cite, please use, Katrina Navickas, ‘Making Moscows, 1839-48′, http://protesthistory.org.uk/7-making-moscows-1839-48′.

By pike and sword, your freedom strive to gain,

Or make one bloody Moscow of old England’s plain.

Handbill posted in Manchester, May 1839.

W. Napier (ed.), Life and Opinions of General Sir Charles James Napier, vol. 2 (London, 1857), p.28.

General Sir Charles James Napier, commander of the Northern District, found the above handbill posted in Manchester during Chartist agitation for the first petition in May 1839.

Physical and symbolic conflicts over territory were central to contested conceptions of power and rights. Activists expressed these struggles within a multi-layered language of place.

The metonym of ‘making Moscow’ implied a city burned to the ground, as Napoleon’s troops had done in Russia in 1812. In July 1839, Stockport Chartist leader James Mitchell, warning of the consequences of government repression, proclaimed, ‘let the people be Peterloo’d and the whole country will be Moscow’d’. When an attempt at insurrection was made in Sheffield in January 1840, Samuel Holberry allegedly encouraged his fellow Chartists ‘to Moscow the town’.[1] Though their rhetorical horizons stretched internationally eastwards, on the ground radicals’ battles over territory were decidedly and defiantly local. Revolution started at home.

[1] TNA, TS 11/816/2688, Sheffield treason trial papers, 1840; Northern Star, 4, 11 January 1840.

Physical force has always been a contentious issue in the history of popular politics, debated by Chartists in their national conventions and by historians ever since. The Chartist refrain of ‘peaceably if we may, forcibly if we must’, however, was always the baseline for constitutional agitation. Physical coercion and the ‘language of menace’ stretched across a spectrum that was responsive to political circumstances and the reaction of the military and local authorities.

From the attempts at a ‘national holiday’ and uprisings in 1839-40, the ‘sacred month’ and ‘plug’ strikes in 1842 and the final push for the Charter in the revolutionary year of 1848, protesters used their knowledge of urban and semi-rural environments, and in response to repression, they developed new tactics, including occupations and barricades of contested buildings.

The tools of protest were not just symbolic, but used the materiality of the environment in which they fought: the cobblestones of the streets, the glass in buildings’ windows and the topography of the urban landscape in town and ‘neighbourhood’. These were battles over knowledge over the landscape and the mastery of space.

1839

Tension built during the early months of 1839, with extensive arms making and dealing, drilling, rumours of ‘ulterior measures’ if the Charter would not pass parliament, and the enforcement of exclusive dealing across the northern industrial regions.[1] The Carlisle Radical Association issued a handbill addressed to the shopkeepers and tradesmen of Carlisle, warning of exclusive dealing:

Call not this an idle threat,

Crimson tears may follow yet.[2]

Authorities feared a ‘general rising’ during the mass meetings of Whit weekend. The Northern Star urged caution in May, and following discussions at the convention, the planned ‘sacred month’ was commuted to the more achievable three days ‘national holiday’ from 12 August. Agitation during the ‘moral demonstrations’ was fired up in reaction to the Rural Constabulary bill passed on 24 July.[3] Special constables, new police and Chelsea pensioners became a major feature of policing Chartist disturbances.[4] The Riot Act was read after agitation at meetings in Dewsbury, Bradford, Colne, Manchester, Burnley, Leigh and Bolton.[5] The industrial towns of Cumberland, Cockermouth, Wigton, Maryport, and Carlisle, also offered the potential for mass unrest.[6] Other areas, including Halifax, Leeds (where an alliance between middle-class reformers and working-class radicals was just about holding fast) and Liverpool (where Chartism was still weak), however, were quiescent. Apart from disturbances in Macclesfield, where a large crowd paraded the streets assaulting police and special constables, Cheshire was also quiet, including unrealised fears that a ‘large body of persons from the manufacturing districts in the North Eastern division of the County’ would attend the Chester assizes for the trial of Reverend J. R. Stephens on 10 August.[7]

[1] TNA, TS 11/815/2683, f.40, Liverpool assizes August 1839, Queen vs Edward Riley and others for training and drilling.

[2] TNA, HO 40/41/416, Carlisle magistrates to Home Office, 13 July 1839. Peter Gurney, ‘Exclusive Dealing in the Chartist Movement’, Labour History Review, 74: 1 (2009).

[3] Chase, Chartism, p. 95.

[4] Swift, ‘Policing Chartism’, 679, 689.

[5] TNA, HO 40/51/57, 101, petition of inhabitants of Bradford to magistrates, 6 May 1839; HO 40/25/608, Magistrates of Burnley to Home Office, 16 July 1839; HO 40/37/808, Smith to Russell, Leigh, 5 September 1839.

[6] TNA, PL 27/11, Queen against John Kay, 19 August 1839; HO 40/41/322-470, 708-738, correspondence of magistrates of Cockermouth and Carlisle to Home Office, March-August 1839.

[7] TNA, HO 40/41/217, Chester magistrates to Home Office, 9 August 1839; /271, Swanwick to Home Office, Macclesfield, 12 August 1839.

Open ‘risings’ occurred in Barnsley on 12 August 1839, and Sheffield and Dewsbury on 12 January and Bradford on 26 January 1840. All failed to attract enough support to even go as far as entering the towns. Part of the failure of the 12 January ‘risings’ can be attributed to the Northern Star, which sufficiently persuading the majority of its readers that the time had not yet come for insurrection. The Sheffield rising was nipped in the bud as a result of the continued effectiveness of surveillance by the magistrates, who quickly acted on intelligence given by the landlord of the pub in Rotherham where the conspirators met, and arrested Samuel Holberry at his home at midnight before he set out.[2]

The rumours and plans, however fanciful, were important in revealing how both radicals and spies imagined a rising to occur and the role of place in them. ‘General risings’ usually focused on attempting to ‘take’ the key buildings representing power and more strategically access to the tools of power: as well as the barracks, they included court houses, magistrates’ offices and town halls. An anonymous letter was sent to Benjamin Heywood, former reformer and now liberal mayor of Bolton, in January 1839, warning that the weavers of Howell Croft planned ‘to fire the town at one end and while the soldiers are engaged at the fire their object [is] to take possession of the town and burn the barracks’.[3]

Police offices, constables and special constables became a particular focus of attack after the introduction of the Rural Constabulary Act. On Monday 12 August, the national holiday began in Dewsbury when ‘early in the morning the cap of liberty was planted on the weathercock at the top of the Market Cross and as early as 5 o’clock bands of music paraded the different villages’.[4] Samuel Holberry’s idea of ‘Moscowing’ Sheffield involved using eight sections of men to converge into the town and take hold of Paradise Square, important not merely symbolically because it had always been the central (and only) open space for political meetings and was the point of symbolic occupation during the silent meetings in September 1839, but also physically and logistically because it gave main access to the main sites of power situated around the square. A bomb would be placed in the police office, and upon its detonation, the Chartists would seize the town hall and adjacent Tontine Inn (another major site of local government meeting) and its coaching yard, barricading themselves in to establish two ‘forts’. To divert the military, attacks were also to be made on magistrates’ houses, the barracks and also in Rotherham.[5]

By contrast, in the Bradford rising two weeks later, the Chartist conspirators realised the impossibility of holding the town indefinitely, and so planned to seize control of the market area to pillage it to equip a baggage train to accompany the Chartist army to Dewsbury, seizing cannon from Low Moor ironworks on the way. But the participants were disappointed when only 300 gathered on a cricket field outside Bradford and were dispersed by the military. The central agitator Robert Peddie, who had only arrived in Bradford from his former base at Newcastle a few weeks previously, escaped to Leeds, where he was arrested four days later.[6]

General Napier had moved his headquarters to Manchester in May 1839 in anticipation of the ‘general rising’. Crucially, he suspected that the trouble would not emerge from Manchester centre and spread outwards, but rather would involve the inhabitants of the satellite towns and villages of the ‘neighbourhood’ converging upon the town. He thus planned to station his forces at the seven main roads leading into Manchester from the north and east, noting ‘the bridges could be easily barricaded and defended against the armed citizens’.[7] The participation of the ‘neighbourhood’ was a key feature of all Chartist and trade union ‘agitation’. As we have seen throughout this period, the out-townships and rapidly expanded industrial villages fostered a strong sense of independence and radical tradition that provided the organisation and personnel for formulating the agitation.

At the radical stronghold of Almondbury on the outskirts of Huddersfield, ‘the Chartists commenced their three days’ holiday by assembling very numerously at the top of Almondbury Bank early on the morning’ of 12 August, and holding meetings in Upper Fold in the village.[8] The ambiguous jurisdiction of townships, especially on county boundaries, and the sheer impracticality of policing rapidly expanding industrial villages a few miles away from the nearest barracks and urban centres, also enabled the ‘neighbourhood’ to play a central role. The period of administrative flux opened by the Rural Constabulary Bill only added to the opportunity. The authorities in Burnley feared ‘simultaneous risings in the towns and villages’ in July 1839, ‘when all employment was to cease for a month and that the meetings were to take place at the different villages so as to evade the interference of the Military’.[9] Many of the meetings to elect delegates, as well as drilling, were conducted deliberately out of urban jurisdictional boundaries, as at Lancaster, where, as the mayor reported, ‘the place where the meeting is being held is close to the extremity of the Borough and is immediately contiguous to the village of Skerton which is out of the Borough … the special constables appointed under the Municipal Act not being authorised to act out of the borough’.[10]

[1] Chase, Chartism, pp. 107-9.

[2] Chase, Chartism, pp. 134-8.

[3] Bolton Archives, ZHE 35/43, anon letter to Heywood, 20 January 1839.

[4] Northern Star, 17 August 1839.

[5] Chase, Chartism, p. 137; TNA, TS 11/816/2688, examinations of Foxhall and Thompson; Baxter, ‘Early Chartism’, in Pollard and Holmes, p. 149; Northern Star 11 January 1840. It was fitting that the funerary procession for Holberry, marking his ‘martyrdom’ in gaol, began from Paradise Square and processed to Attercliffe to meet his coffin on 27 June 1842: Northern Star, 2 July 1842.

[6] Chase, Chartism, p. 138; Leeds Times, 15 February 1840; Peacock, Bradford Chartism, pp. 39-43.

[7] Napier, Life and Opinions, p. 28.

[8] Northern Star, 17 August 1839.

[9] TNA, HO 40/37/608, magistrates to Russell, Burnley, 16 July 1839.

[10] TNA, HO 40/37/652, Armitage to Home Office, 27 July 1839.

In towns where there were barracks, the military commanders still felt they were in danger without extra support. Lieutenant Colonel Cairncross feared for his men quartered in Bolton because ‘the Barracks are overlooked and commanded by every house and Factory in the immediate neighbourhood’. The barracks was situated on Bolton moor, enclosed during the Napoleonic Wars and rapidly built over by working-class residential and industrial development. In the event of a sudden attack, Cairncross resolved ‘that my only plan would be to leave the Barracks to their fate and retire to some Commanding position near the Town’.[1]

[1] British Library, Add MS 54545, fo.20, Cairncross to Napier, 15 April 1839.

Middle-class fear, and the potential for fear, became the main yardstick for measuring illegality. The magistrates of Stockport swore in 250 burgesses as special constables in preparation for a Chartist meeting on 9 May, fearing the worst. But as was the case with most of the mass meetings, the Chartists attempted to abide by the usual process of requisition and negotiation. Each side had different interpretations of what was legal.

One of the Chartist leaders, James Mitchell, called on the magistrates at the court house, requesting an explanation of why the police had informed them that the meeting was illegal, and asking permission to hold the meeting in the marketplace. Henry Coppock, town clerk and legal officer for the corporation, advised the magistrates that the proposed meeting was illegal because of ‘the fears which existed in the borough that a breach of the peace would take place’, and reminded them of ‘the necessity of checking a spirit of insubordination’. Coppock was also anxious to stress that the decision was ‘not a question of party politics’, but a question of public order. Mitchell was ‘evidently astonished at the strength of constabulary obtained’. The magistrates issued a poster warning of the implications of the Royal Proclamation and ordered all innkeepers not to allow ‘seditious meetings’ in their premises.[1]

The Chartists nonetheless met ‘on the outskirts of the borough’ on a plot of ground behind the Stanley Arms Inn, New Bridge Lane. Mitchell addressed the crowd, informing them that the meeting was illegal because it was taking place in the dark, ‘that the Mayor had told them they ought to meet in the daytime, but the Mayor knew they were then immersed in the Factories in their Dungeons’. On 10 May, Mitchell and another Chartist returned to negotiate, and Coppock ‘read to them the law relating to unlawful assemblies’ and warned them that if they attempted to hold a meeting in the streets ‘it would be suppressed so long as they excited the people to arm and resort to physical force’. The Chartists proceeded to have another meeting in the evening, and the magistrates swore in 600 special constables in response.[2] The magistrates of Stockport must therefore have been pleased to receive the opinion of the Home Secretary, Lord John Russell, that the Chartist meeting of 9 May was ‘clearly illegal’.[3] The mayor issued a circular on 22 July warning Stockport inhabitants that ‘the peace of the town is not a political question’, but the actions of the authorities had demonstrated it clearly was.[4]

The Stockport magistrates had sworn in burgesses as special constables. Ratepayers were often obliged by custom and police acts to serve as special constables; during the ‘national holiday’ in August 1839, for example, the burgesses of Wigan and the electors of Bolton were called out.[5] Policing disturbances thus inadvertently or deliberately, reinforced the division between owners of property and renters of commercial premises and the working classes rebelling against them, and between the represented and unrepresented. For the Chartists, this was just one example of there being one law for the propertied and another for the unrepresented.

[1] TNA, HO 40/41/65, printed poster, ‘VR Illegal Assemblies’, 9 May 1839.

[2] TNA, HO 40/41/53, Coppock to Russell, 11 May 1839; /67-68, posters, ‘Long Live the Convention!’ and ‘The People’s Charter!’

[3] TNA, HO 41/14, f. 20, Phillips to Coppock, 13 May 1839.

[4] TNA, HO 40/41/159, printed circular, ‘Magistrates for the borough of Stockport’, 22 July 1839.

[5] Bolton Archives, ZHE 35/58, Heywood papers, poster, 7 August 1839.

1842

The ‘sacred month’ or general strike of August 1842 involved the largest scale and scope of collective action throughout this whole period. From late 1841 onwards, the industrial districts sunk into further and deeper economic depression. The two ‘catalyst’ strikes in Hanley, Staffordshire, in June and Stalybridge, Cheshire, in early August, were both caused by a sudden abatement of wages. But these were triggers for a much larger and political form of collective action. Overall, thirty-two counties were hit with strikes, with the turnouts most extensive in the industrial districts of Lancashire, Cheshire, Staffordshire, the West Riding, Cumberland and Lanarkshire.[1] Two elements of the agitation distinguished it from previous turnouts and the previous ‘national holiday’ of 1839. First, this was a strike constantly on the move: it was spread by large bodies of strikers (a precursor to flying pickets) moving from one town to the next, turning out mills, factories and mines en route by pulling out the plugs from the steam engine boilers. This pan-regional and pan-trade co-operation even took the authorities by surprise. General Arbuthnot wrote from a disturbed Manchester at 11pm on 10 August 1842:

Notwithstanding the information I have received I did not expect that a general turnout would take place in the town in Lancashire to the south of this place and that originally a small mob which had encreased [sic] by degrees would have forced almost all the Mills in the neighbourhood without reference to the description of goods manufactured.[2]

Second, unlike in 1839, the agitation arose from the trades unions, with Chartists keen to use their power for political ends, especially those leaders who had a foot in both camps, such as Richard Pilling of Ashton, the weavers’ leader who was the first to call for a strike for the Charter at a Stalybridge strike meeting on 29 July.[3] In 1839, the national holiday, though couched in class conscious rhetoric, was implemented and conducted in very traditional radical terms and methods, that is, as a demonstration by the ‘people’ against the government. By contrast, in 1842, the impetus originated from the unions in a syndicalist-type form of organisation aimed firstly against their employers, but then aimed more widely at forcing the government to concede to the Charter.[4] As Chase has argued, the political aims of the Charter provided the framework for the unions to look beyond their sectional economic aims. The relationship between Chartist and trade union goals was tense and temporary, and was not acceded to by all, but it nevertheless formed a hugely significant factor in the spread and power of the strike. The key date (as in 1839) was 12 August, and the central node of organisation was Manchester. On the week beginning 12 August, the Chartists held their national convention in the Carpenters’ Hall. On 15 and 16 August, more than 200 delegates representing twenty-five trades and more than twenty localities met in a congress in the Sherwood Inn [had been the Elephant Inn venue of the 38?] on Tib Street and crucially voted to strike until the passing of the People’s Charter.[5]

The hesitancy of NCA and the trades union leadership, however, led to events moving too fast for them to control. They could not shape the speed and passions of the movement on the ground, nor the violence engendered in response to local authorities and the military. Until 12 August, response by the authorities had been panicked and co-ordinated only locally. On 13 August, the government issued a royal proclamation offering a reward for the apprehension of strike leaders and Chartist agitators, and the Home Secretary forwarded instructions to the military commanders and magistrates that they should forcibly resist the turnouts.[6]

Chartists opposed the continuation of the strike as it got out of hand in later August, and, for example, enrolled as special constables in Oldham and other towns in order to suppress the violence.[7] What they found was that strikers and their supporters enacted violence was not a proactive attempt to pass the Charter, but to defend, in part their class, but more to the forefront, their place and community.

[1] Chase, Chartism, p. 212; TNA, HO 45/264/102, ‘account of the strike, Ashton, August 1842’.

[2] TNA, HO 45/268/10, Arbuthnot, 10 August 1842.

[3] Chase, Chartism, p. 214; A. G. Rose, ‘The Plug Riots of 1842 in Lancashire and Cheshire’, TLCAS, lxvii (1957). For the full narrative see Mick Jenkins, The General Strike of 1842 (London, 1980); F. C. Mather, ‘The General Strike of 1842’, in J. Stevenson and R. Quinault (eds), Popular protest and public order (London, 1974); T. D. W. Reid and N. Reid, ‘The 1842 “Plug Plot” in Stockport’, IRSH, 24: 1 (1979); Brian R. Brown, ‘Industrial Capitalism, Conflict and Working Class Contention in Lancashire, 1842’, in Louise A. Tilly and Charles Tilly (eds) Class Conflict and Collective Action (Sage, 1981).

[4] Sykes, ‘Policing Chartism’, 225.

[5] Jenkins, General Strike, p. 143; Manchester Guardian, 17 August 1842.

[6] Brown, Chartism article, 40.

[7] Chase, Chartism, p. 223.

The 1842 general strike enforced the world turned upside down. It brought the cotton districts to standstill as shops shut and magistrates imposed curfews. The stoppages built up a sense of millenarian foreboding experienced during previous disturbances but not to this scale or length of time. Bolton was described as having the ‘appearance of a deserted village’ at noon on Monday 15 August, the very time when the streets should have been busy with factory workers on their dinner break. The wealthier middle classes had indeed deserted, fleeing to make an early summer holiday by the sea at Southport, which mayor Robert Heywood’s sister reported was fuller of company than usual.[1] But the strikes also induced a heterotopia. Strikers initially expressed a sense of optimism about their actions.[2] As Chase points out, given the numbers involved, the incidence of violence was relatively low.[3]

[1] Chase, Chartism, p. 216; TNA, HO 45/249/121, 15 August 1842; Bolton Archives, ZHE 38/62, Hannah to Robert Heywood, 24 August 1842.

[2] TNA, HO 45/264/102-4, in letter from Mayor of Hull, 11 August 1842.

[3] Chase, Chartism, p. 215.

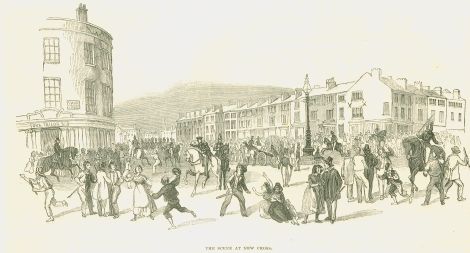

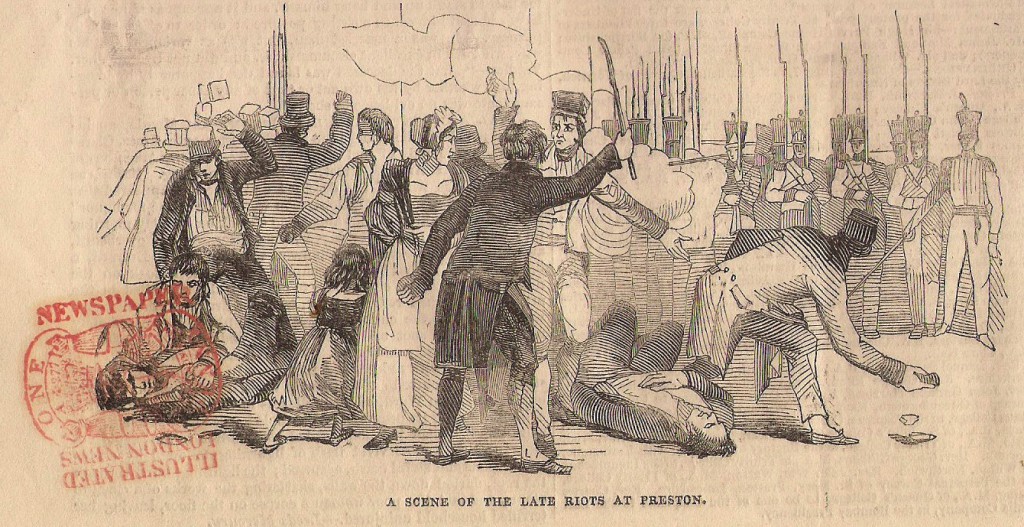

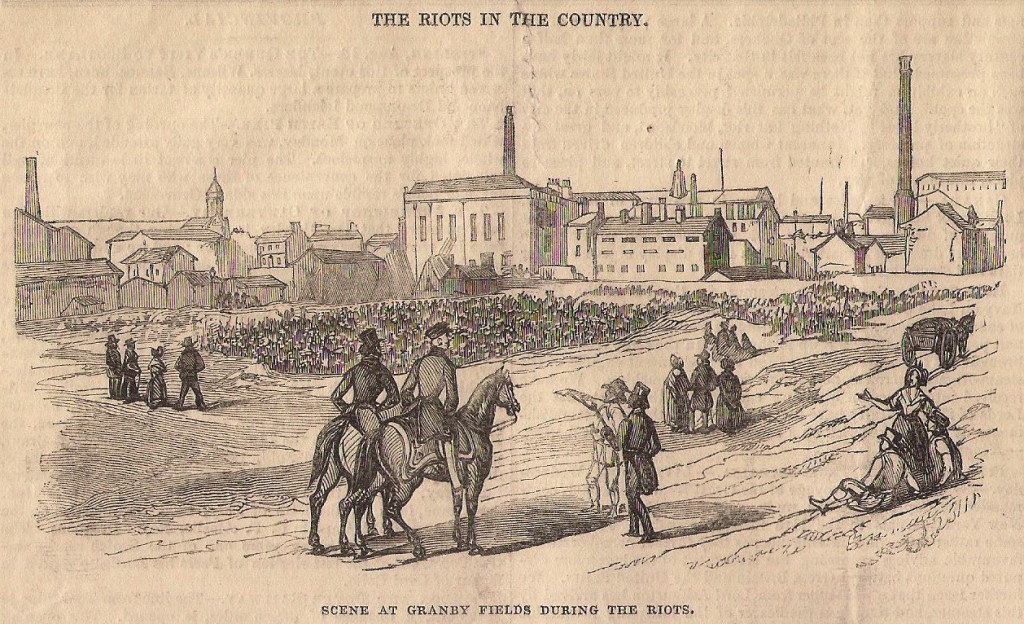

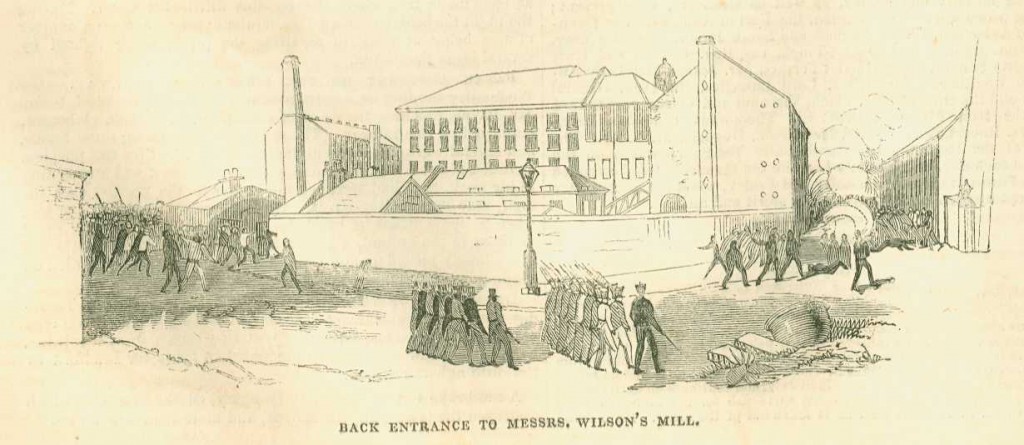

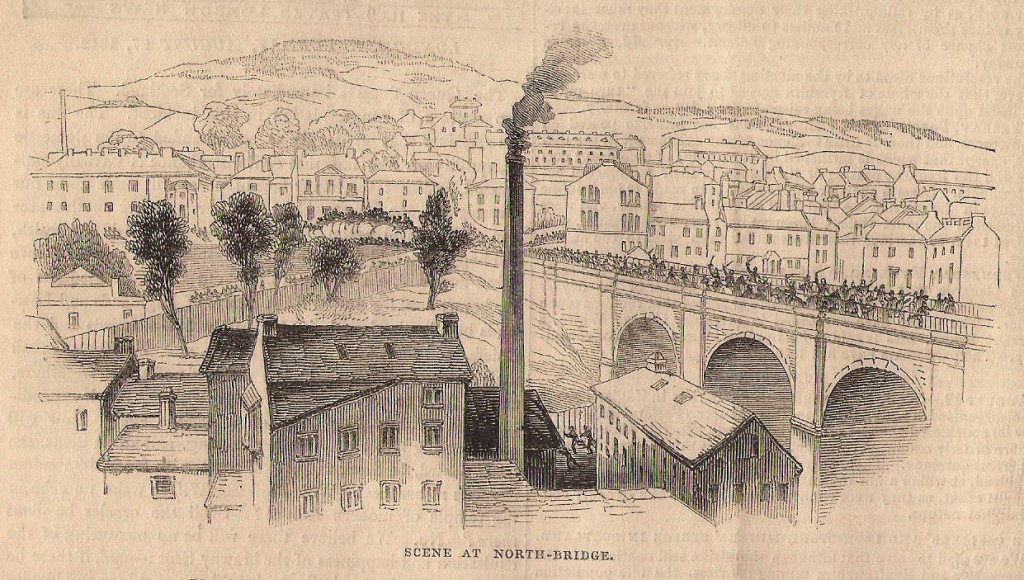

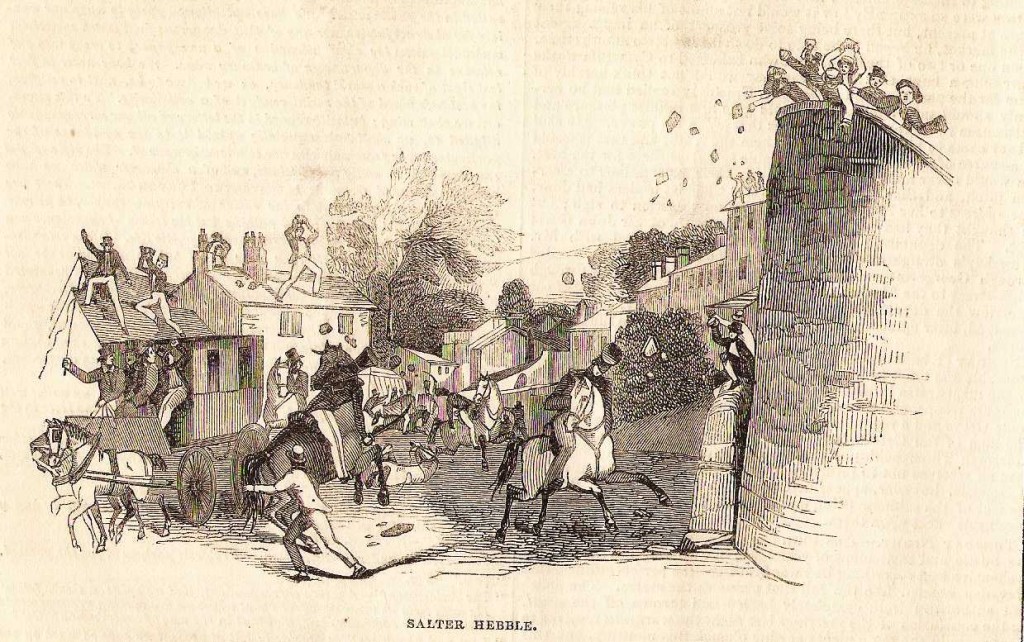

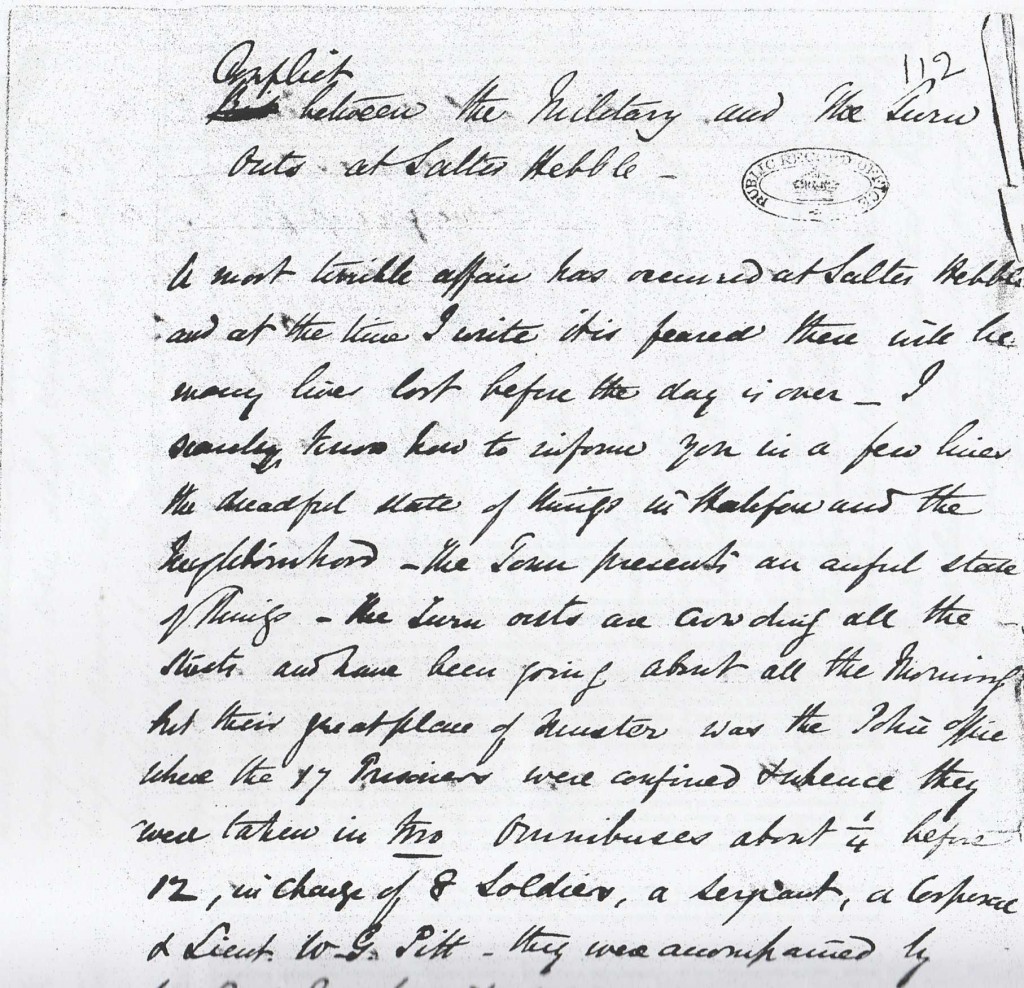

Here are some scenes from the ‘Plug’ strikes and disturbances of August 1842 from the Illustrated London News:

The tensest incidents of the plug strikes involved physical barricades and sieges of key economic and political sites, and strikers using flying pickets. The strikes reached high levels of tension, notably in Preston, where on 12 August, the mayor and magistrates ordered the military to fire on the strikers in a show of force, leaving over a dozen dead or seriously wounded.

The West Riding experienced one of the most dramatic physical battles for territory of 1842, which resulted briefly in a pan-regional movement. Early in the morning of 15 August, Halifax strikers met on Skircoat Moor and processed four miles along the valley, turning out mills en route. They converged with three other groups of strikers at the Pennine rendezvous of Luddenden Foot. The four groups, numbering an estimated 5000 strikers, assembled back along the valley at the King’s Cross on the Burnley Road, making ‘one immense procession filling the whole breath of the road and stretching to a vast length’ to enter Halifax.[1]

Reaching the North Bridge at the top of Halifax about noon, ‘the military and police were drawn up, so as to occupy the whole road and prevent the passage of people, the cavalry being posted in front, the infantry next, and behind them the people and special constables’.

[1] Northern Star, 20 August 1842; TNA, HO 45/264/77, Waterhouse to Home Office, 15 August 1842.

The Illustrated London News depicted an invading army besieging a fortified town. But this was an army of its own inhabitants attempting to reoccupy their own town from the military.

The next day, 16 August, strikers and their supporters sought revenge. The prisoners taken at Halifax were sent to Elland railway station to travel on to Wakefield prison. A rescue attempt failed, but the populace then planned to ambush the carriage of soldiers on their return to Halifax. The soldiers, defenceless in the dip of the road, were ambushed from the embankment above with a volley of stones. The rest of the day was marked by ugly confrontations between strikers and troops in Halifax, resulting in at least three fatalities, including one soldier.[2]

[2] TNA, HO 45/264/112-114

On 8 August 1842, up to 5000 spinners and weavers entered Oldham from Ashton-under-Lyne, and after they succeeded in pulling out the plugs, together with local inhabitants, the violence was aimed at the police. Butterworth recorded in his diary how Mr Wild the superintendent led ‘a force of effective police’ to defend Worthington’s Priory Mill against the approach of 2000 turnouts. The attack centred around getting the gates of the mill open; like a siege, the gates were ‘several times taken and retaken’. Wild was the focus of the attack: he was ‘struck on the head with bludgeons and stones and Mr Clegg another policeman was thrown down, severely cut on the head and wounded in the ribs’. Two men were arrested and taken to the town hall, and 400 special constables were sworn in. It is clear that the Chartists sensed that they were losing control over the passions of the crowd and their desire to oppose the authorities. They first held a meeting outside the National School at which they ‘advised the people to be peaceable’, but the Ashton strikers continued their route through the town turning out the mills. The prisoners were taken to the town hall, and Alexander Taylor addressed the crowds, requesting that they be ‘orderly and he would endeavour to get the prisoners liberated by means of trial’. The crowds however took little notice, attempted to rescue the prisoners, and the magistrates read the Riot Act and sent for military from Manchester.[1]

General Wemyss dealt with the events in Oldham and then had to face the snowballing procession from Ashton approaching Manchester the next day. This incident demonstrated how the problems of suppressing the strike were in part because of its moving nature and in part because the different tactical geographies of the military and the local authorities had not been resolved by experience of the agitation of 1839. The strikers aimed to head to the commercial exchange to negotiate directly with the major manufacturers. Wemyss and Sir Charles Shaw, chief of the Manchester police, decided to take the strategy of a military blockade. They brought out the troops from the Tib Street barracks (in the former heart of radical Manchester) and stationed them ‘across the end of Pollard Street, effectively blocking up the passage with Ancoats’, where the Ashton strikers, heading down Ashton Old Road, were heading. Mr Maud, the magistrate, however, disagreed with this military solution, predicting (rightly) that it would cause violent resistance. He suggested, ‘there should be no disturbance of the Peace, that they should be allowed to proceed through some parts of the Town by a Route to be decided on by him and return to Ashton without holding a meeting’. Maud’s idea of allowing a controlled compromise included allowing the strikers to process through Ancoats, but Wemyss ‘thought it objectionable, because it would be taking them through a part of the Town filled with Irish’. Wemyss proposed to direct the procession through Stevenson’s Square, then into London Road and by Travis Street, back onto the Ashton Road. He described his orders to the troops as a military operation, sending them ‘to take possession of Stevenson Square, forming across it’, and placing some dragoons across Piccadilly to prevent the procession from going down Market Street to the Exchange. The paraders, however, did not follow the constraints determined by the authorities: ‘many of them, instead of following the proper route, broke off and turned into Portland Street’, and Wemyss had to call some of the dragoons from Piccadilly and ‘threw them across Portland Street and thus cut off their progress’.

After a considerable period of negotiation, the strikers were able to continue to Granby Row Fields to hold a meeting (much further south than Maud and Wemyss originally allowed). The question for Shaw had been whether the procession was parading or marching in defiance of the legislation against armed parading with banners – Shaw wrote to the Morning Chronicle to comment on the report of the Chester special commission on the riots. The attorney general claimed that the Ashton strikers induced fear because they were marching ‘in something like military array, six or seven abreast’. Shaw commented that he had warned Maud not to put himself at the head of the procession, exclaiming, ‘I will not be mixed up with this affair, all I can ever do is to count the enemy who are attacking the town’, and that the strikers’ attempt to evade the prescribe route was inevitable.[2] On their return, parties of strikes resumed turning out mills along the Oldham Road.[3] The following day, further disturbances occurred, including at the mill of Mr Birley’s, and at a lockup in Cheetham, where imprisoned strikers were set free and the crowds ‘seized the chests of clothes and accoutrements belonging to the policemen and threw them into the river Irk’, again demonstrating their hatred of the new police. The rioters then turned to the nearby gas works, but were repelled by the military, who arrested two men, two women and a girl.[4] Maud learned his lesson: on the more politically contentious day of 16 August, he described the previous day’s tumults to Benjamin Heywood of Bolton: ‘after the arrival of additional Military Force in the morning we resolved to make a stand and not to allow strangers armed with bludgeons to enter the town’.[5]

Violence in reaction to the military reached a dramatic peak in Preston on 12 August. Context of strikers and industry. The mayor and magistrates had decided to suppress the strikers in a show of force. They marched the military down Fishergate and met the strikers near Lune Street, where the crowd ‘opened two divisions for the purpose of the military passing through, but the orders were to let no one pass’. Following the reading of the Riot Act outside the Corn Exchange, a stone was thrown at the chief constable, which proved the signal for violence: ‘immense bodies of stones [were] now thrown at the police and soldiers’. The crowds used the urban environment against their opponents: ‘part of the mob having gone up Fox Street, they then had the advantage of stoning the military from both sides’. The military fired on the crowd, leaving over a dozen dead or wounded’.[6] Revenge attacks were focused, as in Manchester, on the new police: in Wigan, a police officer reported that on 15 August, a large crowd gathered outside the Police Office calling out ‘this is the Police Office £5 and £10 for a policeman and some of them struck at me with their sticks through the Police Office window’.[7]

Colonel Warre defended the ‘industrious spider’ of Manchester, with all its feeder roads coming in from the satellite towns, by means of a system of ward stations situated in the chain of turnpike tollbars. More than forty mounted special constables were employed to communicate between each station and the military central HQ at the York Hotel (the former town hall of the new corporation) and the magistrates in the town hall on King Street, and to ride out several miles along the main roads to keep watch for approaching strikers.[8] Clear connection with the environment – On Saturday 13 August, the military heard rumours of a party of striking colliers arriving from Pendleton. Riding out to meet them, they ‘came sight of the rioters in a field close to the Bury high road’. Upon an order to charge, ‘the colliers gave legbail, setting off in all directions – scampering over hedges, climbing gates, running through bushes, leaping ditches, swimming the canal, and wading in the river’. ‘Many of the colliers took to earth and burrowed into holes and pits’.[9]

When threatened, strikers employed some of the methods of resistance used in 1839. In Wigton, Cumberland, the strike of miners and handloom weavers was in full swing as late as 23 August. The main targets of violence were not the employers, but, as elsewhere, the military sent to put down the unrest. Major Leigh Goldie reported the response to his regiment’s arrival and parade through the town in the evening: ‘on the approach of the Troops, the rabble retreated up the alleys from which they pelted the Troops’. Strikers also burned ‘bundles of straw in the principal street’ against the military. The industrial towns of Cumberland faced even more problems of a lack of forces of order than the other counties in the north, who at least had some new and reformed policing systems and were not as isolated/as far from different barracks. Goldie lamented that part of the problem of restoring order in Wigton was due to the lack of civil authority:

Of the four magistrates who made the requisition for the troops, Mr Matthews alone was present, he is an infirm old Gentleman, and although he acted with every proper degree of energy and spirit … he is hardly equal to the severe task of patrolling the streets before a Mob; there was no sort of arrangement made by the Civil Powers, there are only three paid constables in the town and Mr Matthews the only magistrate. The few special constables who came forward very late in the evening came without arms of any description…

There is a total absence of any Civil authority in this town and the presence of the military tends to increase excitement.[10]

Agitation in Cumberland was however limited by lack of Chartist support. During the weekend of 20-21 August, the cotton spinners of Dixon, Slater and Chambers’ mills decided to strike, but ‘the operatives were not unanimous and the three principal leaders of the Chartists [Arthur, Bowman and Hanson] were pronounced traitors by many because they would not countenance it’. Arthur, one of the Chartist delegates, had been to Manchester, and returned to tell the meetings ‘to expect punitive instructions in the Northern Star’, but the paper’s decision to denounce further agitation ‘did not altogether please them’. 200 special constables were sworn in to suppress the strikes.[11]

[1] Oldham Archives, D-BUT F, Butterworth diaries, 1842.

[2] Morning Chronicle, 13 October 1842.

[3] TNA, HO 45/268/129, Wemyss to Arbuthnot, 31 August 1842, ‘statement of what occurred in Manchester on 8th and 9th of August’.

[4] TNA, HO 45/268/70, Arbuthnot to Graham, 10 August 1842; Manchester Times, 13 August 1842.

[5] Bolton Archives, ZHE 38/37, Maud to Heywood, 16 August 1842.

[6] The Times, 15 August 1842; Mather, Chartism and Society, pp. 159-60.

[7] TNA, PL 27/11, Information of John Smith of Wigan, 12 September 1842.

[8] Rose, ‘The Plug Riots’; Manchester Guardian, 13, 17 August 1842.

[9] Illustrated London News, 27 August 1842.

[10] TNA, HO 45/243/19, Goldie to Whingates, 24 August 1842; /25, Messenger to Graham, 24 August 1842.

[11] TNA, HO 45/243/2-5, Mounsey to Graham, 22 August 1842; Illustrated London News, 27 August 1842.

1848

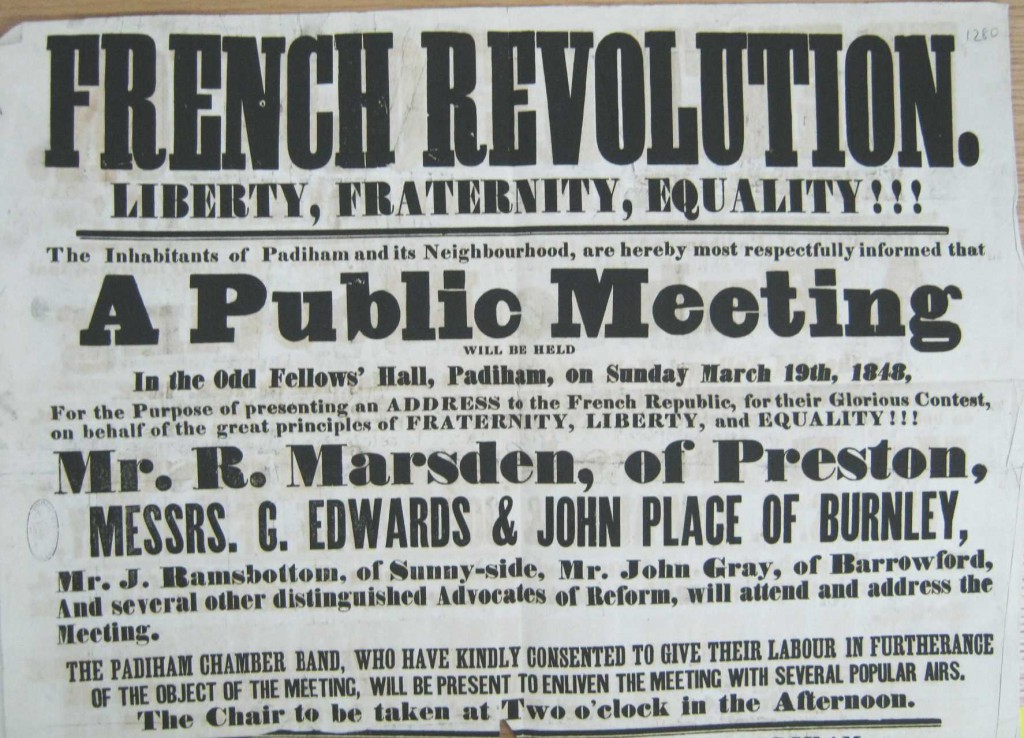

Chartists prepared for the presentation of their third petition in an atmosphere of European revolution in 1848. Some historians have treated the agitation of 1848 as an untidy postscript to their neat argument that Chartism was defeated by Robert Peel’s social legislation and the economic stability of the mid 1840s. Yet the huge wave of demonstrations and violence that resurged with the return of severe economic distress in the textile industries cannot be regarded as an anomaly. It marked rather a continuity of the aims, tactics and leaders that had led the movement since the 1830s. The third petition was backed by the last burst of mass platform radicalism that had long precedents in previous constitutionalist campaigns.[1]

[1] J. Belchem, ‘1848: Feargus O’Connor and the collapse of the mass platform’, in J. Epstein and D. Thompson (eds), The Chartist Experience: Studies in Working-Class Radicalism and Culture 1830-1860 (London: Macmillan, 1982), pp.270, 272.

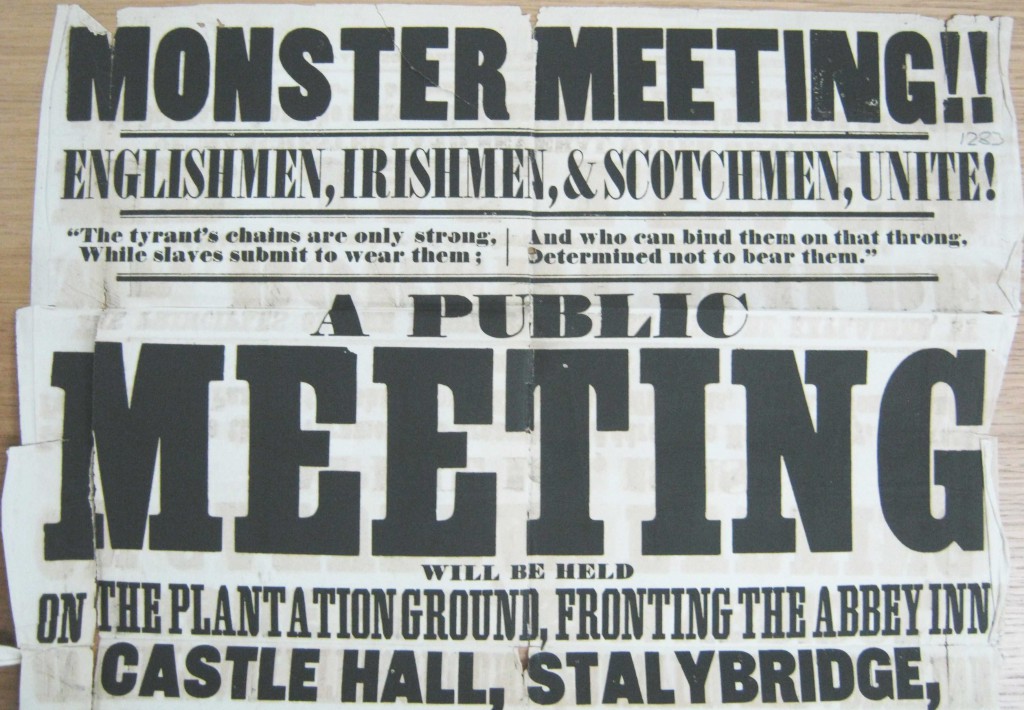

Here are some posters advertising meetings, seized (or taken off the walls) by magistrates and sent to the Home Office in 1848: