This book Protest and the Politics of Space and Place, 1789-1848 is about how both governments and local elites dealt with the rise of mass working-class collective action in this era of revolutions and radicalism. It examines how and why the new movements for democracy and workers’ rights in northern England fought for the right to meet as well as to speak and to publish.

PODCAST: Listen to me talk about the main arguments of the book, Institute of Historical Research, Socialist History Seminar, 6 Feb. 2016, chaired by Keith Flett.

The narrative of popular protest and social movements, 1789-1848

This is an original research article. Please credit if using = Citation: Katrina Navickas, ‘The narrative of popular protest and social movements, 1789-1848′, 2015, http://protesthistory.org.uk/the-story-1789-1848

Popular politics was about contests for space and place, both in terms of spaces to meet and of spaces of representation on local and national governing institutions. The main narrative is of the closing down of public space and the right to protest in reaction to democratic ideas coming from France via Paine and more particularly in response to what became termed seditious assemblies – particularly associated with the industrial working class – but also that local loyalist elites were much more continuous in their policies of repression than any government or legislation.

In Britain, the social and political movements that emerged during this age of revolution included reform and radical societies campaigning for the vote and trade unions campaigning for workers’ rights. They raised these big issues:

- increasing poverty and tightening welfare,

- the right to representation in parliament being attached to the possession of property,

- high prices, low wages and poor conditions for work, exacerbated by manufacturers and farmers moving towards a laissez-faire Smithian economy where prices and wages were unregulated and left to the ‘invisible hand’ of the market.

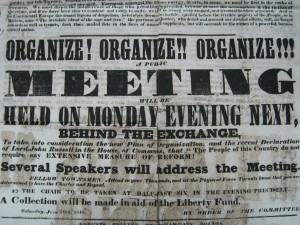

In reaction to these new movements, national and local government clamped down on political meetings and demonstrations in public spaces. Successive governments passed legislation, especially the 1795, 1817 and 1819 Seditious Meetings acts, attempted to control when and where political meetings could take place, and who had the right to hold them.

Go to ‘legislation’ to learn more about the anti-seditious legislation.

But parliament and government was attentive to the constitutional rights enshrined in Magna Carta of the people to petition about their grievances. It was local government – the magistrates and other officials who ran law and order in the nation, who enforced policies designed to root out radical opposition and suppress mass working-class collective action. Throughout this period, 1789-1848, loyalist authorities attempted to exclude radical and trade union participation from political meetings and civic bodies, and intruded on radical meetings with spies and arresting their leaders. The ‘Peterloo Massacre’ of 16 August 1819 proved to be a key point in the development of mass open protest, debates about its legality, and shaping the attitudes of both campaigners for democracy and the loyalist authorities who sought to clamp down on the movement. With the rise of Chartism, the largest ever movement for parliamentary reform and the vote, every political meeting, demonstration, procession, disturbance or debate was a battleground for defending the right to meet and speak, and the space to do so.

In effect, social and political elites privatised public space, at the very time that urbanisation was creating more sites for people to live and to meet.

What’s in the book?

This book surveys the development of working-class political movements from the first radical societies in the 1790s, to ‘mass platform’ radicals after the end of the Napoleonic Wars, to political unions, trades unions and the anti-new poor law movement in the 1830s, and Chartism in the 1840s. It examines their contests with both national government and local authorities through their battles over the right to use public and civic spaces to meet. It discusses the effects of legislation against ‘seditious meetings’, and how political movements developed creative tactics and sites of protest and meeting.

Part I: Spaces of exclusion, 1789-1830

1. Spaces of exclusion and intrusion in the 1790s

The French Revolution polarised popular politics in England. This chapter examines the rise of working-class radical societies and the response by loyalist elites in the 1790s. It argues that loyalism involved enforcing processes of exclusion and intrusion. Radicals were excluded from meeting in civic buildings and pubs, and from taking part in local government. Magistrates intruded into private meetings through spies and arrests. This chapter focuses on the cases of Thomas Walker of Manchester and Joseph Gales of Sheffield, forced out of their business and civic lives by the threat of loyalist suppression. It also examines popular loyalism in the form of burnings of effigies of Thomas Paine and ‘Church and King’ riots.

2. Defending the liberty to meet, 1795-1819

From 1795 radicals and trades unions held mass meetings in politically resonant sites. This chapter examines their defence of the liberty to meet during and after the French and Napoleonic wars. It surveys the response in northern England to government legislation against ‘seditious’ writings and meetings. It underlines the significance of the ‘mass platform’ and its meeting sites, and how working-class groups hired their own meeting rooms and developed networks of delegates and unions across the North. These were sites of contestation over legality and public space. The March of the Blanketeers in 1817 marked a turning point in government fears of revolution and in radicals’ strategies. The chapter concludes with the revival of reform societies in 1818-19, providing the context for the Peterloo Massacre of 1819.

3. Peterloo and the changing definition of seditious assembly

The Peterloo Massacre of 16 August 1819 in Manchester was the defining event of this period. It unified radical groups across northern England and indeed Britain in a shared abhorrence of the authorities’ actions. It also made loyalists across the country and in government reconsider their attitude towards public assemblies and working-class collective action. The ‘Six Acts’ of late 1819 reflected the government’s changed attitude towards ‘sedition’, whereby they moved away from seeking to prosecute for seditious libel and concentrated on public assemblies causing fear among local elites. This chapter then examines the last flourish of radical activity in the Queen Caroline agitation of 1820 before collective action subsided in the 1820s.

Vignette 1: radical locales

This case study examines the ‘locale’ of north Manchester comprising of the Ancoats, New Cross and St. George’s districts, between 1797 and 1840. It locates radical meeting sites and residences to demonstrate the continuity of radical activity in particular areas in successive political movements over generations. It argues that the distinctive socio-economic make-up of the locale, especially of mixed English and Irish immigrants and artisans, fostered such political activity.

Part II: Spaces of the body politic in the 1830s and 1840s

Prelude: the Reform crisis, 1830-2

This short chapter examines the revival of radical and reform activity in the build up to the first Reform Act in 1832. The growth of political unions campaigning for universal suffrage and parliamentary reform was prominent in northern England, drawing strength and spread from the short time movement. Political unions were divided by class, however, and these divisions manifested themselves in contests over meeting sites, particularly in Manchester and Leeds. It concludes by asking whether a revolutionary situation could or did occur in northern England in comparison with the Midlands and southern England.

4. Embodied spaces and violent protest

The 1830s were the ‘age of reform’. This chapter examines the bodily and often violent protests against the Whig reforms and legislation of the 1830s, especially the 1832 Anatomy act, the new poor law of 1834, and the Rural Constabulary act of 1839. Radicals depicted these reforms as part of a Malthusian policy to attack the working-class body and to split up the pauper family. Protesters responded by bodily violence and by invoking ‘disembodied’ fear, through the use of effigies and other corporeal symbols. Trade unions employed violence against strike-breakers, machinery and the new police in defence of their collective body and against a laissez-faire political economy. These campaigns developed the essential organisation and ideologies that fed into the rise of Chartism from 1837 onwards.

5. Contesting new administrative geographies in the 1830s and 1840s

Excluded from the civic body politic, radicals found new opportunities to enter it in the 1830s. This chapter examines how different groups contested not just the spaces of political meeting or the physical imposition of the new legislation of the 1830s, but also the very governing bodies that controlled those spaces and institutions. It follows radicals and Chartists’ contests over positions in the vestry, improvement and police commissions, new poor law and factory boards, municipal corporations and finally, members of parliament. The chapter also surveys further battles over the use of public space and civic institutions. It argues that municipal Chartism was a successful and significant policy that enabled radicals to challenge local elites effectively and to claim part of the civic body politic. Local power was important in and of itself, as well as being a step towards accessing national power.

Vignette 2: processions

This vignette examines the procession as a form of politics on the move. It compares civic, patriotic and radical processions in Manchester and Leeds, showing how their routes were shaped by political events and the changing streetscape. It also discusses the boycott of celebrations of Queen Victoria’s coronation across northern England in 1838.

6. Constructing new spaces

With greater longevity and funding than their predecessors, radicals were able to move beyond ‘spaces of making do’. This chapter examines how Owenite socialists, Chartists, trades unions and the other social movements that emerged in the 1830s hired or constructed detached buildings for their sole use. These sites of meeting functioned not just for immediate campaigns, but for longer visionary goals. These were spaces to enact an alternative economy, a freer religion, an egalitarian education and for entertainment. Association rooms, working-men’s clubs and halls of science reflected a holistic view of how politics should shape communities and their everyday life. These sites faced financial difficulties and the opposition of local elites, but nevertheless offered a new definition of public space.

Part III: Region, neighbourhood and the meaning of place

7. The liberty of the landscape

This chapter examines protesters’ attachment to the landscape. Peterloo reformers became involved in societies for the protection of footpaths in the 1820s. Increasingly unable to hold public meetings in town centres, Chartists and Owenite socialists held monster meetings on fields and moors outside urban jurisdiction. Using the sites and rituals of Methodist camp meetings, moorland meetings reflected a sense of place among protesters. The experience of the environment was physical and elemental, particularly the hard rambles of itinerant lecturers and the secret drilling of radicals at night. The popularity of the Chartist Land Plan among northern industrial workers demonstrated how radicals’ utopian visions of a better life lay in the land as well as the vote.

8. Rural resistance

This chapter examines why Chartism and other ‘urban’ movements failed to take hold in certain regions, but also how other forms of collective action, including agitation against enclosure of common land and the Swing riots of the early 1830s, show that rural areas were far from politically inactive. Luddites, Swing agitators and enclosure rioters enacted a defence of communal rights against privatisation and laissez-faire political economy. They fought for the vestiges of common rights but also the new rights of organised labour against the deskilling effects of mass capitalism in both industry and agriculture. Rural resistance involved embodied practices that transcended the divide between cultural and natural perceptions of the environment.

9. Making Moscows, 1839-48

This chapter surveys the bitter conflicts between protesters, military and magistrates from the attempts at a ‘national holiday’ and uprisings in 1839-40, the ‘sacred month’ and ‘plug’ strikes in 1842 and the final push for the Charter in the revolutionary year of 1848. Protesters used their knowledge of urban and semi-rural environments, and in response to repression, they developed new tactics, including occupations and barricades of contested buildings. These were battles over knowledge over the landscape and the mastery of space. Chartist insurgents and Irish Confederates allied in 1848, but disagreements among the radicals and the more efficient military response diffused any revolutionary potential.

Vignette 3: new horizons in America

Political and religious dissenters sought exile in America, where links were well established through trade and emigration. This vignette examines radical visions of America. Radicals envisaged American wilderness as utopia, with freehold farms underpinning democracy. These ideals coalesced with Paineite ideas of republicanism. But radicals and Chartists quickly became disillusioned with several aspects of mid-nineteenth century America: a lack of genuine democracy in the political system, the persistence of slavery and the difficulty immigrants faced acquiring land. The vignette also compares the situation of British emigrants in America with their counterparts in Australia, where political rights were achieved much earlier.

Networks and organisation of Chartism and Owenite socialism

Owenite socialism found a welcome home in the industrial north, where early co-operation was strong, especially in Manchester and Salford. The co-operative movement had its origins in the anti-mill and anti-truck societies as early as the wartime food crises of the 1790s, and co-operative shops and wholesalers had been operating across Lancashire and Yorkshire since the late 1820s.[1] The grassroots of co-operation and socialism in the industrial North, rather than Robert Owen’s direction from above, shaped the direction of the movement.

The first co-operative congress met in Manchester in May 1831, at which 65 societies were represented.[2] The factory reform movement, and attempts at a wider trades unionism forcefully orchestrated by John Doherty, fiery leader of the spinners’ union and co-founder of the National Regeneration Society with Owen and Todmorden’s radical-Tory manufacturer John Fielden in November 1833, sealed the bonds between Owenite socialism and a campaigning trade unionism. Despite the failure of Doherty’s Grand National Consolidated Trades Union, not least in the aftermath of the Tolpuddle martyrs case of 1834, Owenism in northern England continued to be shaped by the labour movement. After 1834, however, many working-class members moved away from the movement, and through involvement in the anti-new poor law campaign, headed towards Chartism from 1837 onwards.[3]

[1] Peter Gurney, Co-Operative Culture and the Politics of Consumption in England, 1870-1930 (Manchester, 1996), p.12; R. G. Garnett, Co-operation and the Owenite Socialist Communities in Britain, 1825-45 (Manchester, 1972), p.133.

[2] J. F. C. Harrison, Robert Owen and the Owenites in Britain and America (London, 1969), p.226.

[3] Garnett, Co-operation and the Owenite Socialist Communities, p.143. The historiography of Chartism is legion, but the most authoritative and comprehensive study is Malcolm Chase, Chartism: a New History (Manchester, 2007).

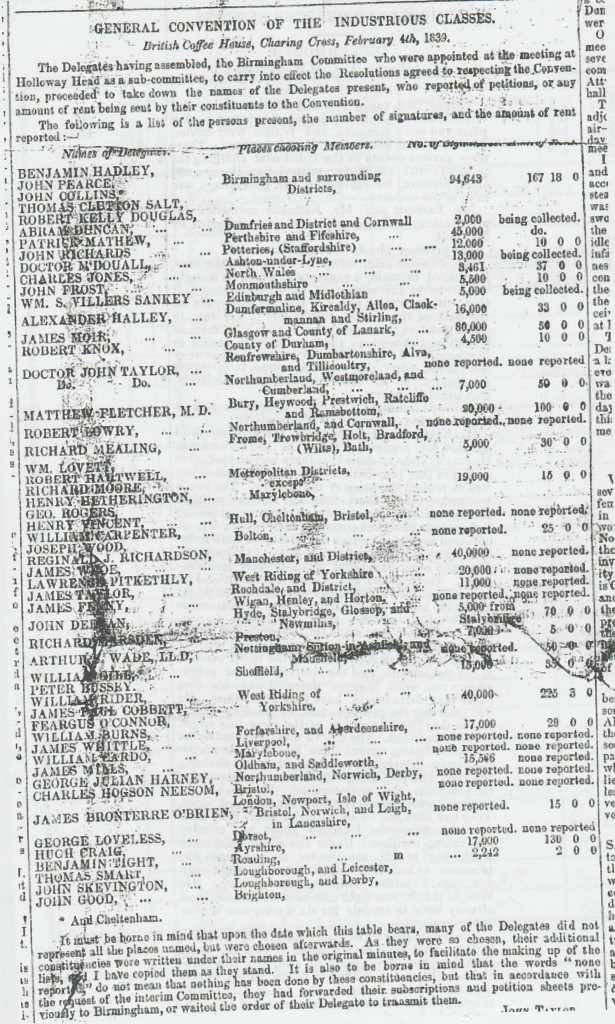

Chartism began not as an organized centralized movement but as a loose network of pre-existing local radical societies with different aims and memberships. Many of these societies had been revitalized by the emotional agitation against the new poor law, and the campaign filtered into early Chartism – demonstrators were as likely to display a banner painted with ‘No Bastilles’ as with ‘the Charter and no surrender’. Organisation was local if not regional. The Manchester Political Union, for example, re-emerged in April 1838 with a ‘council’ meeting every Friday evening in a pub. It oversaw a panoply of ‘branches’ from the expanding districts of Manchester, Salford, and its rapidly populating southern townships.

The organization of Chartist groups at the grassroots worked effectively because in many places it was based on the Methodist model of classes, familiar to many of its members.

In Sheffield, since ‘the nightly meetings in the open air of Chartists having been suppressed by the authorities’, organization was based in the rooms on Fig Tree Lane, the Northern Star reported, ‘other meetings similar to those in use among the Methodists called classes have been established in almost every part of the town, up to 100 classes’.[1] In the larger towns, a district model was also put in place which mirrored if not provided a more democratic alternative to the traditional and new administrative geographies of poor law or police districts or townships. Indeed, Eileen Yeo suggested that the election of class leaders owed more to the increasing participation of the working classes in the vestries than to the more undemocratic structures of Methodist classes.[2]

In Manchester and Salford, divided into districts by the 1827 Police act, the Chartists operated a similar district system for branches of the National Union, each with their own character as defined by the residential character of their bases. District number 6, for example, were the Irish Chartists at Ashley Lane, Irish Town, who took a ‘room occupied by the Socialists’ in June 1839. This was the stronghold of O’Connell’s Irish Repealers’ campaign.[3] Bank Top Union was formed in Minshull Street schoolroom in June 1839, and the Brown Street Chartist association had a room on Travis Street/Brown Street where the plug strikers met in 1842.[4]

In Leeds, Chartists set up affiliated branches in each ward, North, East, South and West, with each meeting in a pub in their respective district, who then sent delegates to the central Northern Union, who met weekly at a ‘large room near St. James Church, York Street’ from February 1839.[5] The structures connected local with central urban, although there were always tensions between maintaining local democracy and organizing centrally for wider aims. The class and district structure became standard for different types of working-class organization, for example, Edward Watkin, leader of the Manchester operative anti-corn law association, organized his members in districts.[6]

[1] Northern Star, 7 September 1839.

[2] Eileen Yeo, ‘Some practices and problems of Chartist democracy’, in James Epstein and Dorothy Thompson (eds), The Chartist Experience (London, 1982), p.553; John Walton, Chartism (London, 1999), p.20. For notions of democracy in Chartism, see Joanna Innes, Mark Philp and Robert Sanders, ‘The rise of democratic discourse in the reform era’, in Joanna Innes and Mark Philp, Reimagining Democracy in the Age of Revolutions: America, Britain, France, Ireland, 1750-1850 (Oxford, 2013), p.216.

[3] Northern Star, 29 June, 13 July 1839; E and R. Frow, Manchester and Salford Chartists, p. 98.

[4] Northern Star, 29 June 1839, 19 September 1840, 10 September 1842; Manchester Guardian, 24 August 1842.

[5] Northern Star, 23 February, 16 March, 3 August, 23 November, 21 December 1839. North East: Sir John Falstaff Inn, St Peter’s Square; East End: London Tavern, Richmond Road, and the Fox, Bank; South End: John Sawden’s beerhouse on Meadow Lane; West End: Angel Inn and General Washington, Caroline Street.

[6] Diary of Edward Watkin, p.184.

1839

The enthusiasm and emotion of early Chartism was whipped into an almost millenarian frenzy by the revival of mass platform meetings in the second half of 1838 and early 1839, in the expectation that the Charter would be granted immediately upon presentation of the national petition to parliament.[1] This practical and hands-on activity meant that organization was neglected. We should not however take a Fabian disdain towards this lack of desire to centralize; indeed, enthusiasm was the glue holding these burgeoning network together, and petitioning and mass meetings the most effective way of gaining support. Chartists were able to capture and channel the emotion of the anti-new poor law movement to their cause to achieve a large amount of support very quickly.

After the rejection of the first national petition in July 1839, supporters of the Charter felt a huge disappointment and emotional come down. Rather than ending in ‘burn out’ as experienced by many social movements, however, the leadership channelled their anger into a reassessment of tactics and rhetoric and, as Iorwen Prothero has shown, ‘the conclusion that it would take a long time, years of steady work, to gain the Charter’.

The first national organization, the National Charter Association (NCA), was formed at the Griffin Inn, Ancoats, Manchester, in July 1840. Take up of the NCA was slow nationally, with only eighty localities having registered by February 1841. About 3200 membership cards had been distributed in Manchester and Salford, that is, only a quarter of the nearly 12,000 people who signed the second national petition in the towns in 1842.[2]

Again we must not exaggerate the extent or indeed the desire to centralize. Fear of prosecution under the 1799 act against corresponding societies no doubt influenced reticence to join the NCA. The NCA reached its peak around the time of the second petition and general strike, with trades societies swelling the organization to 400 ‘branches’ (though technically the structure was illegal under the 1799 act) and about 50,000 members. Its strength as expected lay in the industrial north and midlands, and this divide was no doubt exacerbated by the separation from London radicals. Malcolm Chase underlines the ‘breathtaking arrogance’ of Henry Hetherington’s Metropolitan Charter Union, who issued a statement that ‘it would be useless and impolitic to incur the expense of sending delegates to Manchester’.[3]

Mistrust of Feargus O’Connor also divided the movement. A rival, anti-O’Connellite National Suffrage Union formed in Birmingham, and many other groups sympathetic to the Charter kept their independence. Nevertheless, the NCA was significant in having membership open to women on equal terms as men, and in providing an organizational focus that succeeded in corralling together so many different interests into supporting their programme, not least the 1842 petition, which collected up to three million signatures.[4]

The geography of Chartist organization from 1840 could be categorized as national, with local branches loosely tied to central committees based in town centres, who then sent delegates to the National Conventions. But it was not as tidy as that (and following Massey’s model, to avoid determinism or reductionism, we should not expect it to have been tidy). Self-identity, autonomy and democracy was a vital fuel keeping Chartist branches going. They were connected in other ways, not least itinerant orators and leading figures, especially O’Connor, who toured almost all the time, and the ‘imagined community’ fostered by the Chartist press. The main role of the district councils of the NCA became to direct a veritable missionary force of lecturers.[5]

Moreover, Chartism, and indeed other political movements, were just one part of the complexity of working class identities and communities. Moreover, movements are not composed solely of paid-up members. As Prothero has shown in the case of the NCA, a membership card was not seen as an essential aspect of participation, and the localities engaged in myriad educational and leisure activities that were not directly related to the central committees’ political programme.[6] This is applicable to most movements. A spectrum of commitment and support made up all socio-political movements in this period, and for many, signing the petition or going to a demonstration were the marks of their support, rather than sacrificing a proportion of what little earnings they had for a cause that increasingly seemed difficult to achieve immediately.

[1] Iorweth Prothero, Radical Artisans in England and France, 1830-1870 (Cambridge, 1997), p.222.

[2] Pickering, Chartism and the Chartists, p.53.

[3] Chase, Chartism, p.160; Northern Star, 20 June 1840.

[4] Chase, Chartism, p.163; Prothero, Radical Artisans, p.222.

[5] Prothero, Radical Artisans, p.223.

[6] Prothero, Radical Artisans, p.223.

Class

Were the battles over the freedom of speech and meeting and the campaign for the vote and for workers’ rights a Marxist form of class struggle? Or were social movements inclusive, encompassing ‘the people’ rather than class, and searching for social justice rather than revolution? Influenced by Gareth Stedman Jones’s ‘rethinking’ of Chartism, John Belcham emphasises the radical rhetoric of the ‘people’ and the inclusive rituals of the mass platform processions and demonstrations as fostering a wider solidarity that joined ‘workers whose material experience of industrialization diverged considerably’.[1] Owenite socialists certainly envisaged unity above sectionalism, though they never achieved it in practice. A major reason for this failure was the inter-reaction between political movements and governing elites. The loyalist reaction of the 1790s, the impact of the Peterloo massacre of 1819, the pulling up of the drawbridge of representation in 1832, and the solidifying of the middle-class alliance with old elites in repression against the Chartists and trades unions in the 1840s, led not to populism but to much stronger class consciousness forged in struggle. And though radicals looked to America and France for democracy, they were increasingly disillusioned by the continuance of old elites and forms of government in both countries.

Political movements drew their strength from their sense of place – but for much of this period, that place was by necessity local. The inward-looking nature of some groups was forced upon them by an understandable fear of being infiltrated by spies and agents-provocateurs as well as hostile newspaper reporters and arrests of leaders by local authorities and by government. Hence movements spread cautiously, with periodic periods of heterotopia followed by contraction, and, for more subversive groups, a structure of cells and tickets to maintain anonymity. But to search for the longevity of national organisations as a way of proving the existence of class consciousness or indeed the success of movements is misleading. As studies of Chartism have shown, radical movements had to be locally-based and loosely federated rather than homogeneous.[2] The goals of reform, universal suffrage and workers’ rights were simultaneously national and translated into local circumstances by local leaders of a diverse range of political and social groups.

[1] J. Belchem, ‘The Waterloo of peace and order: the United Kingdom and the revolutions of 1848’, in D. Dowe et al (eds), Europe in 1848: Revolution and Reform (Oxford, 2001), p.248.

[2] P. A. Pickering, Chartism and the Chartists in Manchester and Salford (London, 1995), p.54.