Manchester township had 23,000 inhabitants according to a local census of 1773; by 1801, the general census enumerated over 70,000 inhabitants, a trebling of the population within a generation. It was to triple again by 1831.[1]

Manchester was the centre of the cotton textile trade, and was the nodal point for all its ‘satellite’ towns and villages producing cloth by mills as well as by handworkers.

zoomable map of the 1832 electoral boundaries

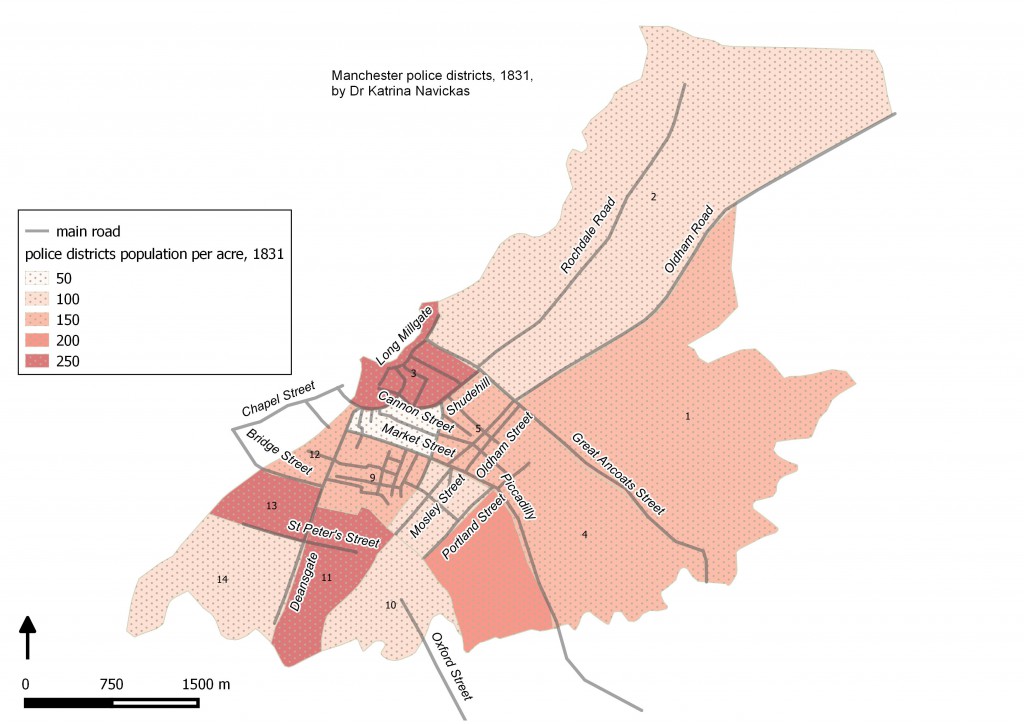

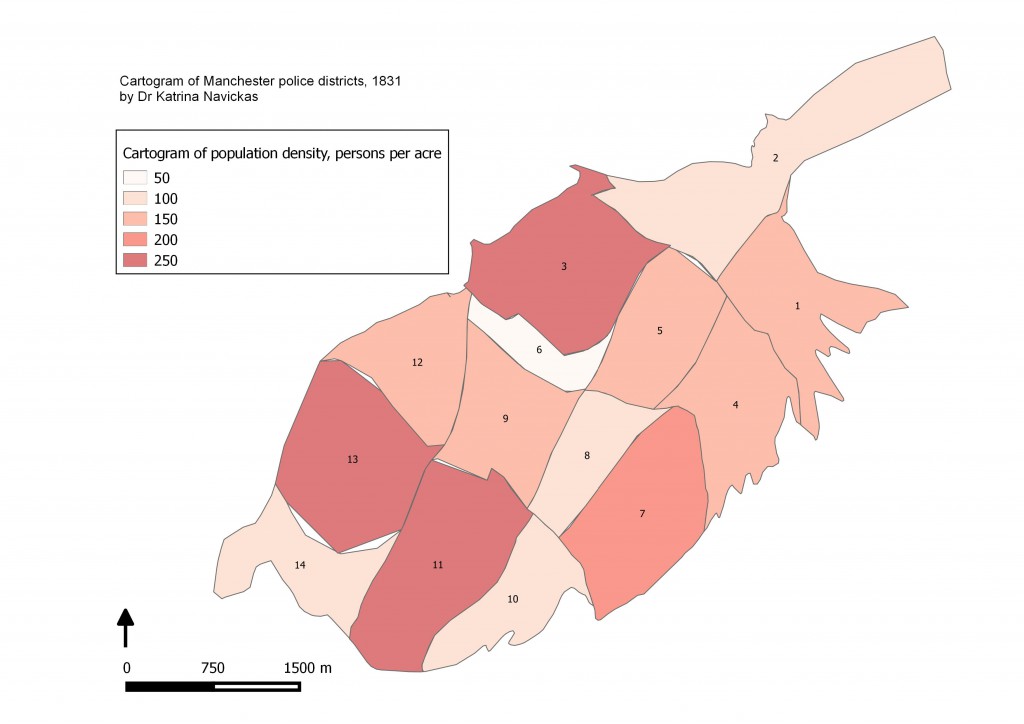

Police districts, 1831, colour coded by population density (persons/acre) & cartogram

In 1844, French economist Leon Faucher observed the ‘curious’ industrial topography of Lancashire:

Manchester, like a diligent spider, is placed in the centre of the web, and sends forth roads and railways towards its auxiliaries, formerly villages, but now towns, which serve as outposts to the grand centre of industry.[1]

[1] L. Faucher, Manchester in 1844 (1844), p. 15.

The Manchester improvement commissioners conducted a travel survey in February 1808; they calculated that over 1700 wheeled vehicles, 4500 horses and 200 cattle entered the town over a period of just four days.[1] The busyness was amplified on market days. The New Manchester Guide of 1815 noted the effects of merchants from ‘the adjacent country and neighbouring towns’ entering Manchester on market days: ‘Tuesday morning never fails to afford matter for admiration in strangers, from the quantity of cotton goods which are dragged through the streets in the carts and wagons of bleachers, dyers, printers, etc.’[2]

[1] Manchester Archives, M91/M1/21, report 6 April 1808.

[2] New Manchester Guide (1815), p. 186.

Unlike most of the other commercial towns in northern England, therefore, Manchester acted as the centre of a much larger radius of population, who regularly travelled into the town for trade, work and play. It was this critical mass of inhabitants from towns such as Rochdale, Oldham, Bolton, Wigan and Stockport, and the hill villages surrounding them, who formed delegations to radical meetings in Manchester, and were a major part of the reform demonstrations that led up to the Peterloo Massacre of 1819.

This huge rise in population had a major impact on the nature and development of political activity in Manchester. The town expanded rapidly, but was also constrained by its medieval governance structure, which was run by a lord of the manor and court leet as well as boroughreeve and constables until Manchester was finally incorporated in 1838. Even then, the old authorities refused to disband, and in 1839, during the height of Chartist unrest, there was the bizarre situation of two town halls (the proper one on King Street, and the magistrates in the York hotel next door) running two rival police forces.

A phalanx of High Tory and Orange magistrates, including clerics from the Collegiate Church (now the cathedral), and the notorious ‘thief catcher’ deputy constable Joseph Nadin, kept a firm hand against any reformist political and trades union activity in the area, aided by their colleagues on the bench across the manufacturing districts.

[1] M. Nevell, ‘The social archaeology of industrialisation’, in E. Casella and J. Symonds (eds), Industrial Archaeology: Future Directions (New York: Springer Academic, 2005), p.187.

Map of political meetings in Manchester and Salford, 1789-1848:

The most obvious patterns in the sites of meeting in Manchester were:

- the loyalist, local government and ‘patriotic’ meetings (marked in blue and yellow) tended to cluster in the old medieval part of the town, around the Collegiate Church and nearby Exchange, at the top of Deansgate

- radical and trade union meetings (marked in pink) took place all over, but clustered in Ancoats and New Cross (now the Northern Quarter), and as Manchester expanded southwards, in Chorlton-upon-Medlock (down Oxford Road).

- St Peter’s Fields became a key site for radical meetings from 1816 onwards, and after Peterloo (1819) became a site of radical and Chartist ‘pilgrimage’ for processions on the way to meetings

Read more about the north Manchester ‘locale’

Loyalism in Manchester and Salford:

Read more about loyalist pubs in Manchester

Chartism in Manchester and Salford:

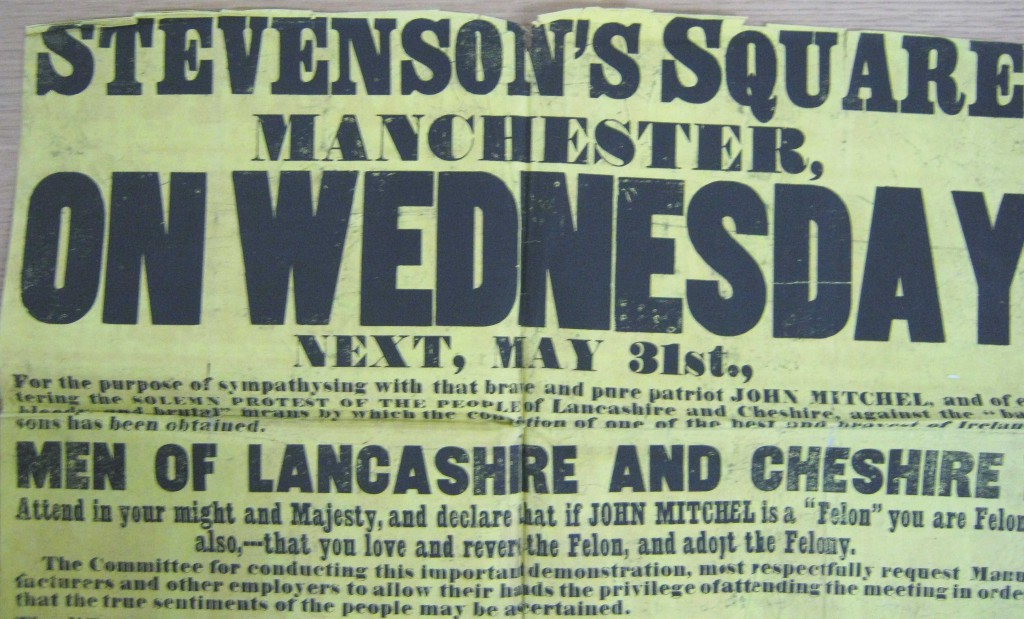

Stevenson’s Square

The Chartists adopted Stevenson’s Square as their main urban outdoor meeting site.

Property investor William Stevenson bought part of the estate of Sir Ashton Lever in 1780 (covering most of what is now the Northern Quarter), and developed the square and its surrounding residences as a rival to St. Ann’s Square. The area never became as fashionable as Stevenson had desired, and by the 1830s had the gritty red-brick and warehouse character that it maintains today.[1]

The earliest record of the square being used for public meetings that I can find is on 27 November 1834, when a meeting was held ‘to petition the king on the present crisis’ of economic distress.[2] Daniel O’Connell gave a speech on the repeal campaign in the square in September 1835, and Chartists colonized the square from 1838 onwards.[3] In May 1839, around 5000 people attended a meeting to elect a delegate to the National Convention, and there were mass meetings there throughout the Chartist period, especially at times of concerted agitation. During the final push for the third petition, the Chartists held meetings in the square almost every day in April and May 1848.[4] From 1841, the ACLA and the operative anti-bread tax association used the square for mass meetings, and other allied movements including the plug strikers in August 1842 and the unemployed in April 1848.[5]

[1] Parkinson-Bailey, Manchester, p. 8.

[2] Morning Chronicle, 29 November 1834.

[3] Preston Chronicle, 19 September 1835.

[4] Northern Star, 11 May, 13, 20 July 1839, 15 February 1840, 2 January 1841,3 June 1848; Manchester Times, 22 August 1840, 2 October 1841; Manchester Guardian, 8 May 1839; Halifax Guardian, 8 April 1848; TNA, TS 11/137/374, Liverpool Special Assizes, 1848.

[5] Edward Watkin diary; Manchester Times, 19 February, 16 April 1842; TNA, HO 45/269/29; TS 11/137/374.

Poster advertising a Chartist-Repeal meeting on Stevenson’s Square, 1848:

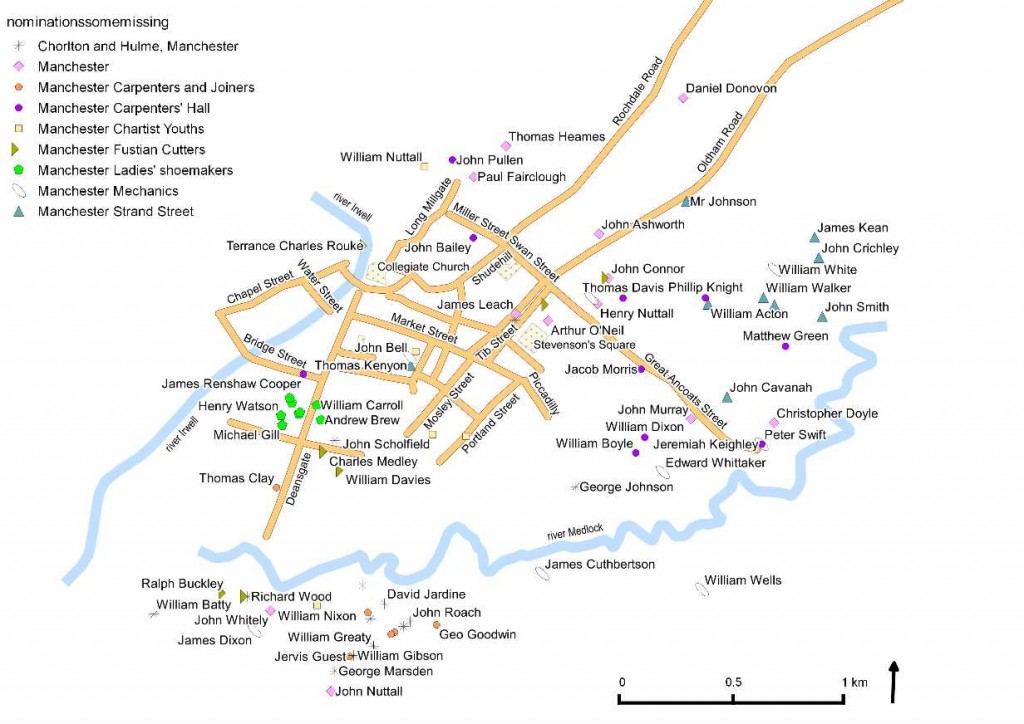

Nominations to the Chartist National Convention, 1841-2:

list of branches:

Yellow = Carpenters and Joiners’ branch

Blue – Strand Street branch

Red = Manchester central

Pink – Chorlton and Hulme

Blue circle = Fustian Cutters

Green = Ladies’ shoemakers

Purple = Mechanics

white pushpin = Carpenters’ Hall

small red = Youths’ branch

praying man = 1842 nominations

white = Painters, 1842

The National Charter Association operated a district system, each of which had its own character shaped by its residential makeup.

District number 6, for example, were the Irish Chartists at Ashley Lane, Irish Town, who took a ‘room occupied by the Socialists’ in June 1839. By the 1840s, Manchester had expanded considerably southwards on the former Chorlton Hall estate and beyond the Medlock river. This shift was reflected in the structure of radical and trades’ organisation and meeting sites.

The nomination lists to the Chartist general delegate council in 1841 illustrate the range of the different groupings. Some were geographical, such as the Strand Street group in New Islington and the Chorlton and Hulme branch. The delegates from the Carpenters’ Hall, a main meeting site situated to the south of the town near the river Medlock, however came not from the immediate area around but from Ancoats and New Islington, suggesting that activists crossed the town regularly for meetings. Others were trade-based, notably the Ladies Boot and Shoemakers, who were clustered around the shops on the middle of Deansgate. The Mechanics and the Fustian Cutters were by contrast spread out across the town.

Read more about northern Manchester – Ancoats, New Cross, Oldham Road and New Islington – on the next page.

Protest and the Politics of Space and Place Extended by Katrina Navickas is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.