Luddism and Swing riots had long precedents in the history of rural protest.

Attacking machinery, by fire or by force, were common methods of intimidation, protest and resistance throughout later eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. James Hargreaves’s spinning jenny was forcibly dismantled in 1767; cotton weavers demolished carding engines around Blackburn and Richard Arkwright’s water frames at Chorley in 1779; machine breaking flared up in parts of Lancashire, the West Country, and the Midlands in 1780 and again in 1792. Individual acts of sabotage during trade disturbances were also common.[1] There were parallel disturbances in industrialising regions of France against the introduction of machines and the consequent reduction of skill. Francois Jarrige’s study of the French agitation reveals strikingly similar patterns of organisation, based on local communities and involving folklore and folk ritual in the performance of machine breaking, to those of the Luddites in northern England.[2]

The Luddite machine-breaking of 1811-12 and the Swing riots of the early 1830s differed from previous outbreaks of machine breaking and arson because they were meta-movements, as Peter Jones has termed them.[3] The predominant model of rural protest history was established by Eric Hobsbawm and George Rude in their classic study Captain Swing, in which historians are drawn to finding ‘moments’ of popular protest, spectacular incidents, that take place within, and are proof of, ‘movements’ of the labouring poor.

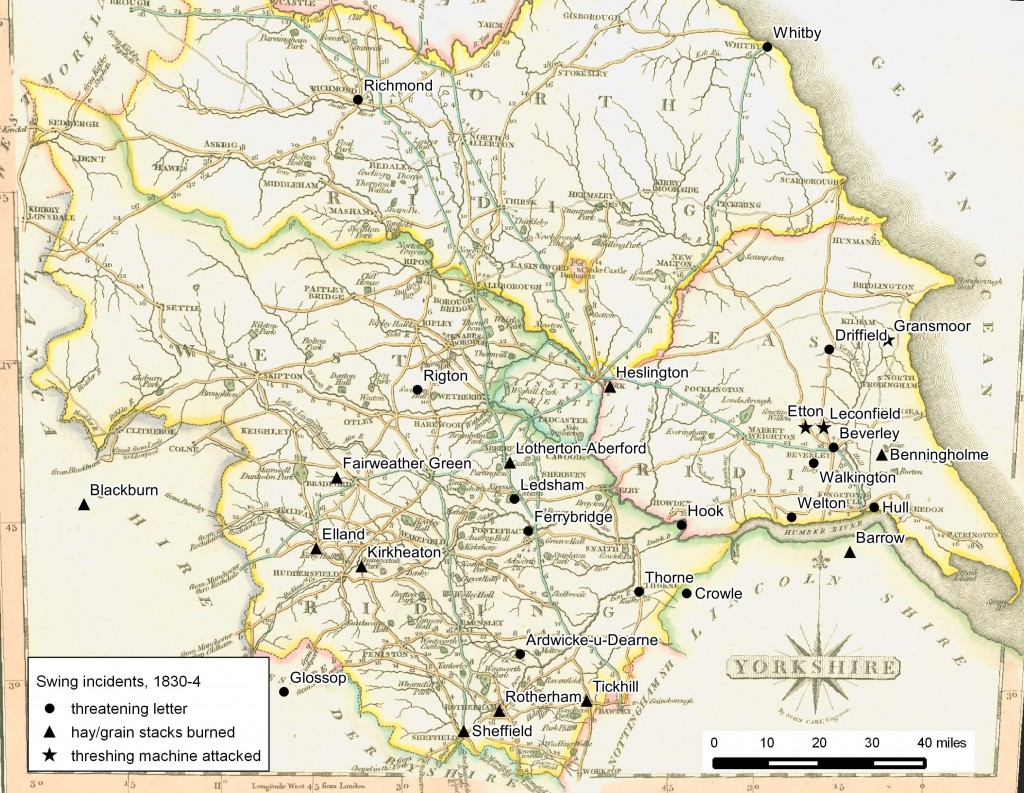

Rural historians and geographers have recently rethought and in some cases completely reversed Hobsbawm and Rude’s highly influential interpretation of Swing. Rather than framing the disturbances within a grand narrative of the development (or failure to develop) class consciousness, these have shown how the predominant method was arson of stacks and ancilliary activity such as exacting quete and threatening letters, rather than machine breaking as Hobsbawm and Rude calculated. They have given much closer attention to the specific socio-economic contexts of the outbreaks within broad but defined regional patterns. A whole range of causes lay behind the agitation but a common thread was the defence of livelihood and skill against all these changes.[4]

Luddites and Swing rioters were enacting a defence of communal rights against privatisation and laissez-faire political economy. They were fighting for the vestiges of common rights but also the new rights of organised labour against the deskilling effects of mass capitalism in both industry and agriculture.

Locations of Swing agitation in northern England, early 1830s:

View Swing 2 in a full screen map

Moreover, what also united disparate groups of protesters was mythology created out of folklore, popular custom, and the imagination. The mythical figures of General Ludd and Captain Swing provided a powerful force in many ways: to encourage solidarity among different groups of industrial workers, to enforce an atmosphere of silence among local communities harbouring agitators, and to invoke a sense of fear among the authorities locally and nationally. Ludd and Swing were imagined leaders with a specific purpose: they represented charivaric community justice (drawing from popular carnival customs of men wearing women’s clothing, ribbons and sashes, and adapting popular ballads about the brave men of their localities) with militaristic discipline and threat, perhaps as a reversal of the hierarchical mobilisation of volunteer and militia regiments during the Napoleonic Wars. Lacking nationally prominent leaders to take up their cause, workers used the imagined figures to connect and strengthen their groups pan-regionally, in an imagined geography held together by anonymous letters between, say, Nottingham and Leeds.[5]

But the meta-movements were also shaped by the sensationalism of the newspaper press in connecting incidents together, and indeed, the willingness of the magistrates and military to believe that they were searching for General Ludd and Captain Swing. The emergence of ‘Rebecca’ in the tollgate riots in Wales in the 1840s demonstrated the power of the metonym and the imagination in creating and sustaining meta-movements against new political economies embodied in machinery, plantations and roads. D. J. V. Jones’ and more recently Rhian E. Jones’s studies of the Rebecca rioters again show how physical force tactics combined with folk culture and ritual were not ‘primitive’ reactionary responses to grievances because they were not mutually exclusive from so-called ‘modern’ forms of organisation such as petitioning.[6]

Legislation against arson and similar nocturnal crimes against property was tightened up in 1827 and 1828, although this was counter-acted by the ruling from 1827 that parishes were no longer obliged to compensate victims of incendiarism, forcing landowners to turn to the costly option of private fire insurance and thereby raising the risks and stakes of arson. [1]

[1] Poole, ‘A Lasting and Salutary Warning’, 166; Archer, By a Flash and a Scare, pp.72–3.

John Cary’s 1823 map of Yorkshire:

[1] Cumberland Pacquet, 16 November 1799, sabotage of the engine pumps of Dykes’s colliery on the Dovenby estate, Cumberland.

[2] Jeff Horn, ‘Machine breaking in England and France during the age of the revolution’, http://www.historycooperative.org/journals/llt/55/horn.html; Francois Jarrige, Au temps des tueuses de bras; Francois Jarrige, Vincent Bourdeau and Julien Vincent, Les Luddites

[3] Peter Jones, ‘Finding Captain Swing’, Southern History, 32 (2010).

[4] Steve Poole and Andrew Spicer (eds), Captain Swing Reconsidered: Forty Years of Rural History from Below, special issue of Southern History, 32 (2010); Adrian Randall, ‘Captain Swing: a retrospect’ and Carl Griffin, ‘Swing, Swing redivivus or something after Swing? On the death throes of a protest movement, December 1830–December 1833’ in IRSH, 54: 3 (2009); Carl Griffin, ‘The violent Captain Swing?’, P & P, 209 (2010), 149–80.

[5] Kevin Binfield, The Writings of the Luddites (Baltimore, 2004).

[6] D. J. V. Jones, Rebecca’s Children: A Study of Rural Society, Crime and Protest (Oxford, 1989); Rhian E. Jones, Petticoat Heroes (University of Wales press, 2015)

For more on enclosure and rural resistance, see the Edgelands page

The agricultural depression of the early 1830s hit the arable districts of the North. The clerk of Kilham vestry solicited the aid of major landowner Thomas Duesbery of Beverley for the ‘industrious Poor of the said Parish – who at this inclement season of the year – wages being low and flour as well as other articles exceedingly high, are in great distress’. The members of the vestry couched their plea for assistance in terms hinting at the possibility of social hierarchies fracturing: ‘amidst all the outrages that have been committed in the Country – they have steadily evinced a most loyal and peaceable disposition – no disturbances nor outrages with regard either to breaking Thrashing Machines or burning Stacks having taken place in the Parish’.[1]

[1] Hull History Centre, UDDU/11/33, Stephenson to Duesbury, 25 January 1831.

Arson was a common tool in the repertoire of organised labour in urban areas; it was not a solely rural or ‘backward’ tactic. Sawyers and joiners seem to have been particularly active incendiarists, with their easy access to flammable materials which either made the connection more likely or at least made them the most obvious suspects. In June 1833, a master joiner of Oldham lost his house to a suspicious fire. The magistrates suspected the involvement of the joiners’ society as the action followed a successful strike among joiners for higher wages, and formed part of wider agitation including threatening letters sent to employers warning against their employment of blacklegs.[1]

On Sunday 11 December 1830, for example, a fire was started in the large warehouse in the colour works of Messrs Popple and Co in Hull, and on the following night ‘a paper was put under the counting house door, containing the words in an ordinary handwriting, “Remember Swing, beware”.[2]

[1] TNA, HO 64/3/364, Whitehead and Barlow to Home Office, 27 June 1833.

[2] Hull Advertiser, 17 December 1830.

3 thoughts on “rural resistance and the Swing riots”