Popular protest is about space and place.

Social movements use spatial tactics, the most obvious of these being demonstrating in or occupying public sites.

Local and national governments often attempt to suppress oppositional protests that threaten their authority by excluding protesters and political groups from meeting in civic and ‘public’ spaces.

Whether it was the conflicts over where the Occupy movement could camp, or public outcries against ‘defensible architecture’ used to deter homeless people, the use of ‘poor doors’ in new-build developments, or the gating of Manchester Library Walk on the very site of the Peterloo Massacre of 1819, there is a certain continuity in planners’ attitudes to people on the margins of society and to the meaning and uses of public space.

Plus ca change. In the nineteenth century, local elites attempted to use ‘improvement’ in street design and new police forces to exclude political opposition as well as vagrants and other marginalised members of society from meeting in streets and civic buildings.

Political groups and social movements therefore use and claim public space in protest. Both urban and rural protesters defended their communities against dispossession and exclusion from their customary places of work and meeting, their landscapes and economies, and ways of life. Political movements contested who had the right to speak for their town and their people, and represent them to the nation. They also creatively responded to exclusion through constructing their own buildings and meeting sites, and looking to wider horizons.

What’s in the book?

My book examines how and why the new movements for democracy and workers’ rights in northern England fought for the right to meet as well as to speak and to publish. Popular politics was about contests for space and place, both in terms of spaces to meet and of spaces of representation on local and national governing institutions.

The main narrative is of the closing down of public space and the right to protest in reaction to democratic ideas coming from France via Thomas Paine and more particularly in response to what became termed seditious assemblies – particularly associated with the industrial working class – but also that local loyalist elites were much more continuous in their policies of repression than any government or legislation.

By the end of this period, new opportunities emerged that allowed much larger and longer-surviving movements notably the Chartists and Owenite socialists to re-enter the civic body politic, contest representation and create their own spaces of meeting.

A quick note on enclosure:

February 2016 – two articles published that have relevance to my work:

First, this article by Bradley Garrett about contemporary disputes in Lancaster over ‘common’ land: http://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/feb/10/battle-for-freemans-wood-lancaster-common-land-locals-property-development

1. Some of the tactics seem quite familiar to a historian of rural protest: ‘In addition to filing an application for three well-trodden footpaths across the wood to be officially recognised, a council document records that “local people took exception” to the No Trespassing signs and “they disappeared”. Those signs that remained were subversively mutilated’.

2. A quote from the article about the company who are going to build on the land in Lancaster: ‘The firm owns more than 30 properties in England, and had submitted an informal planning proposal in 2010 to build housing in Freeman’s Wood. According to John Angus, director of Lancaster arts organisation StoreyG2, the lodging of that proposal means:

this scrubby patch of land has direct links to global economic, political and social networks.

This statement chimes exactly with what I argue about Doreen Massey and David Featherstone’s arguments about how local people defending local places could be connected to multi-scalar layers of space – from the local to the global at points in time. And even if they are defending the place for very localist reasons, they are still taking part in a wider struggle informed or in this case shaped by global structures, which, Massey argues, have a very uneven geography determined by the power of capital.

The other article is by Mark Hailwood on the Many Headed Monster Blog (and indeed echoes a comment on the Guardian article btl) about the complex history and meaning of enclosure:

https://manyheadedmonster.wordpress.com/2016/02/08/a-walk-in-the-park-history-from-below-and-the-english-landscape/

Historians of enclosure will warn any more idealistic land campaigner that the popular view of the ‘common’ (to quote the Guardian article, ‘common – a place formally defined as “pertaining or belonging equally to an entire community, nation or culture”’) wasn’t quite so rosy in practice. There was never such a thing as purely ‘common’ land in early modern Britain – it always belonged to private owners, but commoners were those people who had customary rights to use it for grazing, gleaning, etc.

Not everyone was a commoner; not everyone (certainly not an ‘entire community, nation’) had those customary rights. As Andy Wood has defined, place was custom because it was defined by customary rights, and therefore the people who belonged to that place were those who were also defined by those rights. Enclosure was the process of the main landowners taking away those rights and monopolising the economic and social uses of the land, but the variety of landholding practices and processes (copyhold, various sorts of leases etc) often meant that enclosure was not resisted and indeed was applied for by commoners.There’s links to some excellent studies of early modern land rights and enclosure on Mark’s page, and he notes how commoners could and did switch sides mid-disputes. So although resistance to enclosure – and particularly the stopping up of footpaths – was significant, it was not total, and it certainly wasn’t a complete story of ‘property owners versus the common people’ that perhaps the more popular view of enclosure likes to think it was.

The Politics of Exclusion:

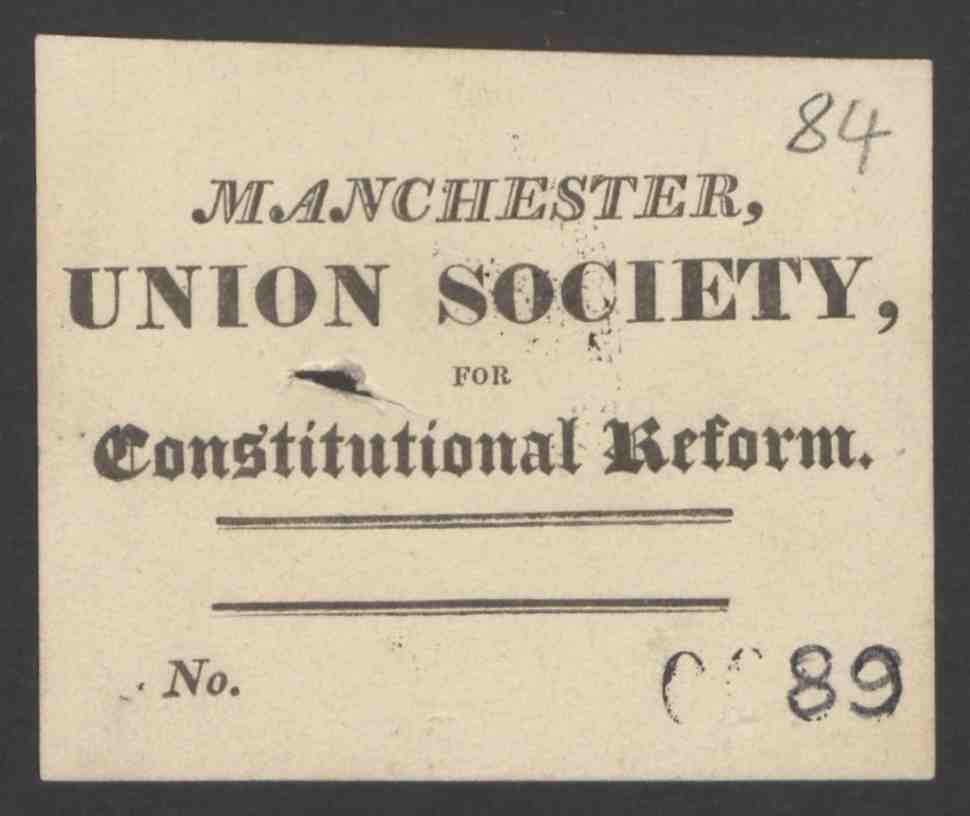

This is a membership card for the Manchester Union Society for Constitutional Reform from 1817. It is now in the Home Office papers at the National Archives, Kew. It was seized as evidence when the leaders of societies campaigning for the vote and reform of parliament were arrested under the suspension of habeas corpus (meaning they were held without trial) in March 1817.

What does it represent?

- the struggle that working-class people took up in the cause of the vote (universal suffrage), and reform of the corruption and elite-control of parliament

- the belief in constitutional, democratic and peaceful change and the rights of man

- the fight against government suppression of oppositional groups, and the use of legislation against them, from the banning of political reform meetings and the imprisonment of radical leaders without trial, and against local elites’ attempts to suppress radicalism, a battle that reached its tragic apogee at Peterloo two years later

- the right to meet, discuss, write and publish political ideas

- Manchester identity and pride as the great workshop of the world, but also as a place of liberty and change

These are the rights and beliefs that should still resonate with us today. Reformers were imprisoned and died for the sake of the vote, and we need to remember them.

Class

A major question relating to the changes of this period usually involves class. Were the battles over the freedom of speech and meeting and the campaign for the vote and for workers’ rights a Marxist form of class struggle? Or were social movements inclusive, encompassing ‘the people’ rather than class, and searching for social justice rather than revolution?

Influenced by Gareth Stedman Jones’s ‘rethinking’ of Chartism, John Belchem emphasises the radical rhetoric of the ‘people’ and the inclusive rituals of the mass platform processions and demonstrations as fostering a wider solidarity that joined ‘workers whose material experience of industrialization diverged considerably’.[1]

Owenite socialists certainly envisaged unity above sectionalism, though they never achieved it in practice. A major reason for this failure was the inter-reaction between political movements and governing elites. The loyalist reaction of the 1790s, the impact of the Peterloo massacre of 1819, the pulling up of the drawbridge of representation by the Reform Act of 1832, and the solidifying of the middle-class alliance with old elites in repression against the Chartists and trades unions in the 1840s, led not to populism but to much stronger class consciousness forged in struggle. And though radicals looked to America and France for democracy, they were increasingly disillusioned by the continuance of old elites and forms of government in both countries.

Political movements drew their strength from their sense of place – but for much of this period, that place was by necessity local. The inward-looking nature of some groups was forced upon them by an understandable fear of being infiltrated by spies and agents-provocateurs as well as hostile newspaper reporters and arrests of leaders by local authorities and by government. Hence movements spread cautiously, with periodic periods of heterotopia followed by contraction, and, for more subversive groups, a structure of cells and tickets to maintain anonymity. But to search for the longevity of national organisations as a way of proving the existence of class consciousness or indeed the success of movements is misleading. As studies of Chartism have shown, radical movements had to be locally-based and loosely federated rather than homogeneous.[2] The goals of reform, universal suffrage and workers’ rights were simultaneously national and translated into local circumstances by local leaders of a diverse range of political and social groups.

[1] J. Belchem, ‘The Waterloo of peace and order: the United Kingdom and the revolutions of 1848’, in D. Dowe et al (eds), Europe in 1848: Revolution and Reform (Oxford, 2001), p.248.

[2] P. A. Pickering, Chartism and the Chartists in Manchester and Salford (London, 1995), p.54.