Sheffield 1823

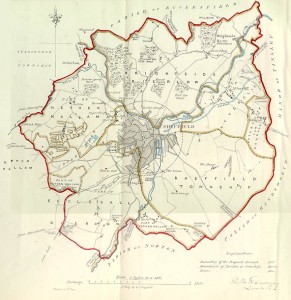

Sheffield 1832 electoral boundaries

Paradise Square

The story of radicalism and collective action in Sheffield begins and ends in Paradise Square.

Read about the history of Paradise Square – http://www.sheffieldhistory.co.uk/forums/index.php/topic/6534-paradise-square/

The Sheffield Society for Constitutional Information, formed in 1791, had their headquarters in the Freemasons’ Hall on the northern edge of Paradise Square. Large meetings to petition for parliamentary reform were held in the square from 1795 onwards.

The square was distinctive because, unlike in other towns, it was the only square where all major political meetings of all types were held. So it never became associated solely with one political group, and indeed became a site of contestation between many. It is enclosed on all sides by bourgeois Palladian-fronted houses, and is also unusual for its gradient.

The Chartists had their headquarters on Fig Tree Lane, a narrow lane around the corner from the bottom of the square.

The most significant meetings occurred in the summer and autumn of 1839, at the height of Chartist agitation. The Chartists developed the tactic of the ‘march on the churches’ across northern England, and in Sheffield, Chartists attended the nearby parish church en masse. The march on the churches only turned violent in reaction to authorities’ suppression in Sheffield. On 8 September, the authorities stationed detachments of police ‘in several parts of the church and at the doors; and orders were given to permit any man who pleased to enter, but on no pretence to suffer any one to come out till the conclusion of the service’ (Manchester Guardian, 18 September 1839).

The Sheffield agitation was particularly significant because it led to a further inventive evolution of tactics. The Chartists held nightly silent meetings in Paradise Square as protest against the royal proclamation against open air meetings and their treatment in church.

Silence not only made it impossible to be arrested for seditious words; it also overturned the usual and expected aural experience of Chartist occupation of public space, that is, noise, speeches or music. The Chartists stood in defiance of any potential for the authorities to ‘kettle’ them or enact another Peterloo (which may have had even more brutal consequences as, unlike St Peter’s Fields, Paradise Square is enclosed on all sides with only narrow exits).

The demonstrations were preceded and followed by processions, and Eileen Yeo described the mass procession following the silent meeting on 9 September as ‘almost as if beating the bounds of public property’ (E. Yeo and S. Yeo (eds), Popular Culture and Class Conflict 1560-1914 (Brighton: Harvester Press, 1981), p. 159). This was another defensive measure against the spaces of assembly closing in on them. After four successive evenings of protests, the magistrates issued a placard prohibiting public meetings in the square and sent in the police to disperse the crowds. The Chartist committee retreated to their rooms in nearby Fig Tree Lane, but decided to continue the processions to church on the following Sunday. On Sunday morning, the police were stationed in Paradise Square to prevent the Chartists from assembling, and the churchwardens of the parish church disallowed any meeting in the churchyard, locking the church gates prior to the service (TNA, HO 40/51/559, Sheffield town hall to Normanby, 14 September 1839; Northern Liberator, 7 September 1839; Northern Star, 7 September 1839). The clash of authority passed off peacefully but showed the symbolic potency of ‘public’ spaces and further exclusion of radicals from them.

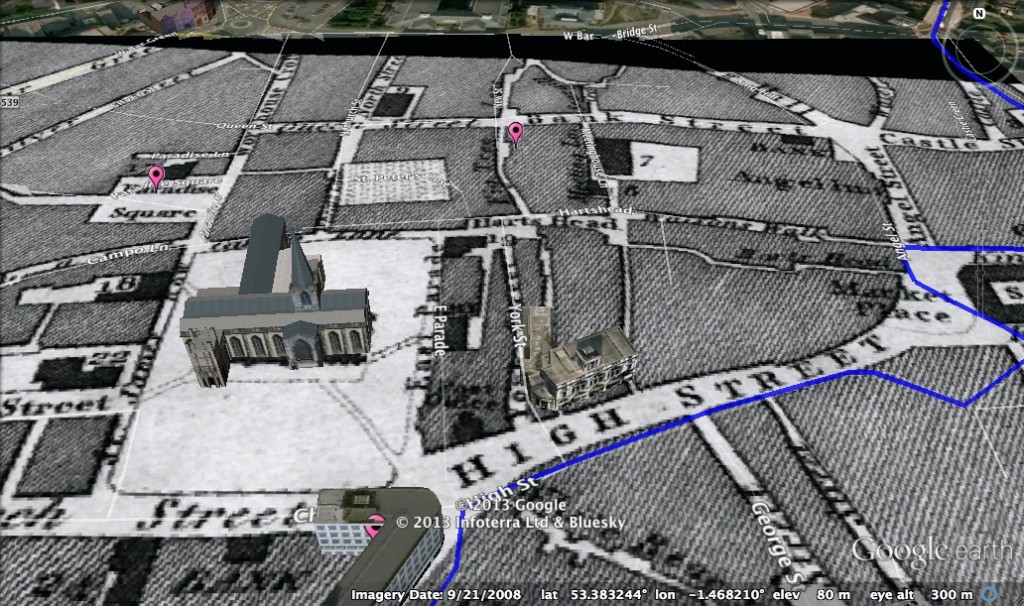

Map of political meetings in Sheffield

Further reading

- A. Seaman, ‘Reform politics at Sheffield, 1791-1797′, Transactions of the Hunter Archaeological Society, 7 (1957)

- E. Yeo, ‘Culture and constraint in working-class movements, 1830-1855’, in E. Yeo and S. Yeo (eds), Popular Culture and Class Conflict 1560-1914 (Brighton: Harvester Press, 1981)