This is an original research article. To cite, please use: K. Navickas, ‘edgelands’, http://protesthistory.org.uk/moors/edgelands

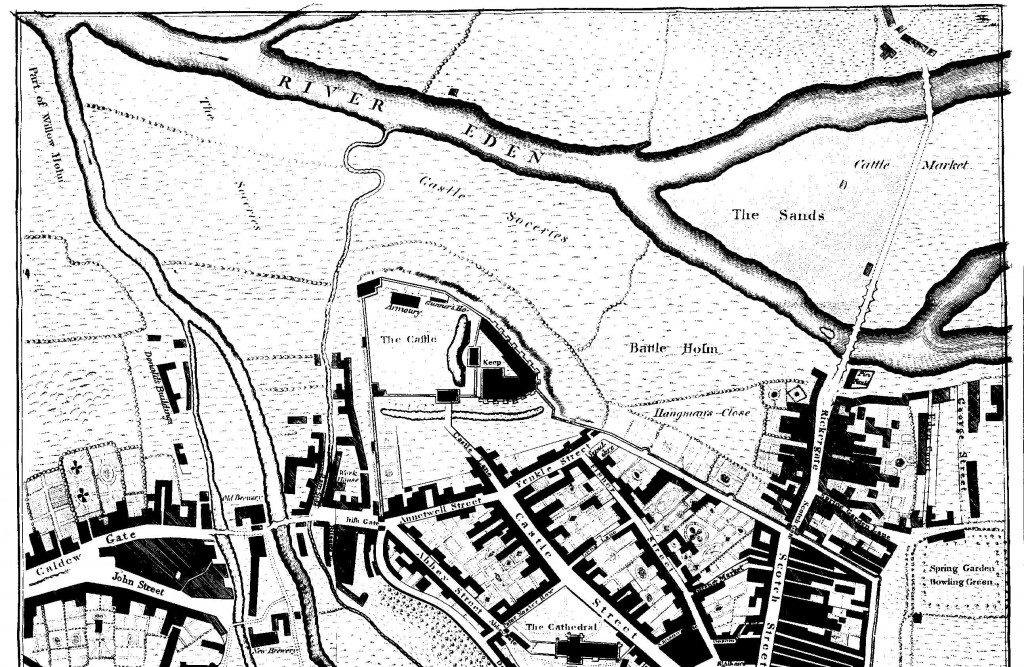

Mass meetings often took place on the edgelands, in places outwith jurisdictional boundaries. These were liminal spaces in between urban and rural, scrubland and building land that was often the by-product of urban ‘improvement’.[1] In Carlisle, the mayor had refused to allow reform meetings within the city boundary. Jeremiah Jollie, the proprietor of the Carlisle Journal, hosted the first open air meeting of reformers on New Year’s Day 1817, on an open space at Willowholme adjacent to the weaving districts of Caldewgate and Shaddowgate. The estuary site of the Sands was also commonly used for political meetings.[2]

Such sites could be places of desperation, sought out because of the restrictions on meeting in the newly improved squares and open spaces in town centres. But spaces of the mass platform were also places of familiarity. Inhabitants from a wide area were able to access such sites easily as they were often situated between town and ‘neighbourhood’, on familiar footpaths and rambling routes, spaces for leisure and everyday life.

[1] See P. Farley and M. Symmons Roberts, Edgelands: Journeys into England’s True Wilderness (London: Random House, 2012).

[2] J. Barnes, ‘Popular protest and radical politics: Carlisle, 1790–1850′ (PhD dissertation, Lancaster University, 1982), p.206; Liverpool Mercury, 10 January 1817.

The topography of towns shaped the appearance and movement of protest. Oldham town centre for example has expansive views across the region, which enabled the Bankside Mill strikers of 1834 to spot the oncoming arrival of troops and plan accordingly: Butterworth noted, ‘scouts it is said were placed on the tops of the mill and the rioters scampered away before they could have behold [sic] the plumes of the soldiery rising the brow from Manchester’. Notably the strikers held early morning meetings on Oldham Edge each day to plan tactics.[1]

[1] Oldham Archives, D-BUT F/20, Butterworth news reports, 1834.

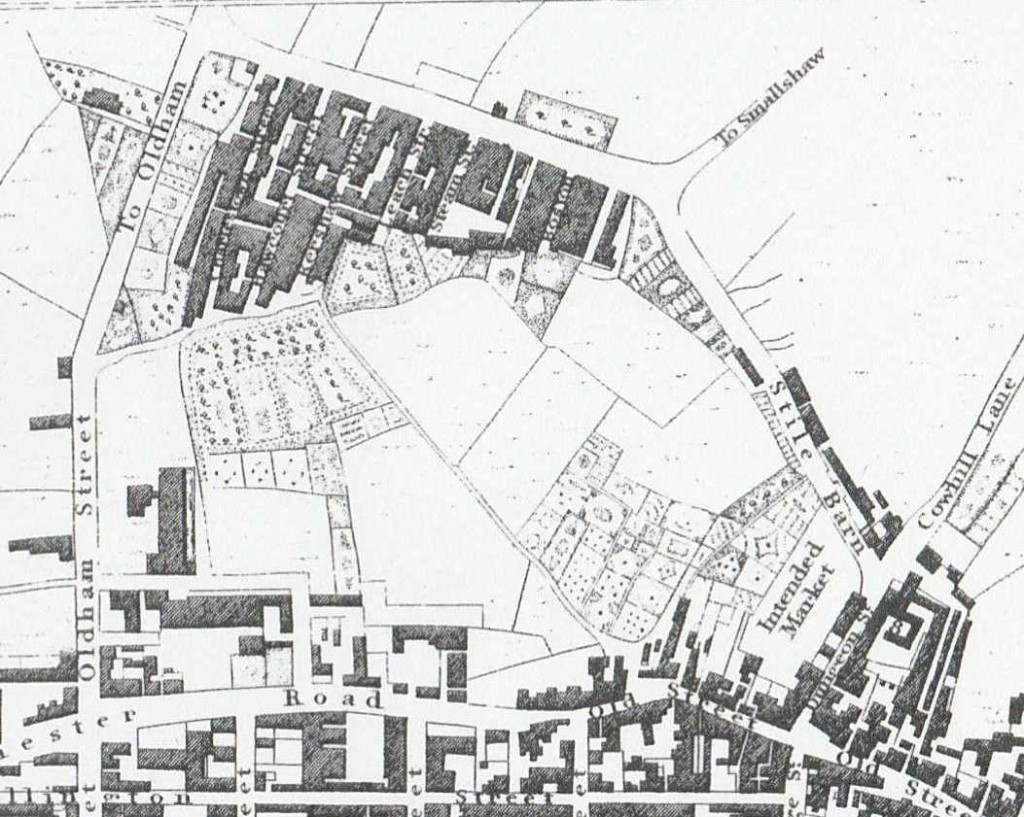

During the plug strikes of 1842, in town centres, scrubland between houses and on the edge of working-class residential districts were sites of meeting. Strikers met every day at the Haigh off the Manchester Road in Stalybridge; on waste ground behind Thacker’s Foundry in Ashton-under-Lyne; on the waste ground near Cheapside in Hyde, and on Waterloo Ground in Stockport.[1] Oldham strikers met every day from 8 to 13 August on Curzon Ground behind the Albion Inn on Lord Street, a site previously used for election hustings, anti-new poor law demonstrations and Chartist meetings.[2] In Carlisle, turnouts met in their regular place, ‘a lot of vacant ground amongst the houses in Rigg Street, Caldewgate’, and in Bradford, Chartist and trades delegates met on a ‘brick ground outside Mr White’s’ on Manchester Road.[3] Often strikers used fields on the outskirts of towns after their initial meetings, usually in marketplaces, were dispersed by the magistrates.[4]

[1] The Trial of Feargus O’Connor Esq and Fifty-Eight Others at Lancaster (Manchester, 1843), pp.14, 22, 29-33, 43; MT, 27 August 1842; Jenkins, General Strike, p.74.

[2] Oldham Archives, D-BUT F/81, Butterworth news reports, 1842.

[3] TNA, HO 45/243/2, Mounsey to Graham, 22 August 1842; NS, 20 August 1842.

[4] NS, 20 August 1842; Trial of Feargus O’Connor, pp.29-33.

The effects of enclosure

first ed. OS map, 1847, Bolton, Lancashire:

The process of enclosure demonstrated connections between custom, memory and the land, and how these factors cemented the ways in which inhabitants understood the consequences of enclosure and broader changes to their landscapes.

The notebook of John Albinson, the surveyor for Bolton, Lancashire, recording the proceedings of the enclosure of Horwich Moor in 1816, shows the role of place and how it was defined. However rapidly Bolton was industrialising and urbanising, older forms of tenancy and agriculture and rural life were still dominant in the out-townships and villages. The book included a list of objections from the tenants of Lostock Hall estate, the small farmers of which faced loss of their common rights. By using the phrase ‘known Moor all his/her life’, witnesses demonstrated their attachment to their locality as well as to these rights, and how they defined place by custom and memory.[1] Nearby Tonge Moor had been enclosed in 1805, and examinations of its smallholders expressed similar feelings.

Adam Greenhaulgh, aged ninety, pleaded:

He has known Tonge Moor ever since he was a Boy – that he lived close to Tonge Moor for sixty years – says he was primer and looker over Harwood Lee Common which lies near to Tonge Moor. Says that since he knew Tonge Moor the Occupiers of Lands in Tonge and Haulgh always turned their Cattle upon Tonge Moor.[2]

He expressed a sense of place in relation to the human lifecycle and to customary practices. In asserting common rights and practices legitimised by ‘time immemorial’, witnesses attempted to contest or subvert the calculating place-less political economy of the enclosers and agricultural improvers.

Reading against the archival grain, there are also echoes here of a back history of private negotiations and rumours. J. M. Neeson’s seminal study of resistance to enclosure argued against historians’ dismissal of inhabitants’ ‘grumbling’ over enclosure rather than opposing it in physical action. Prefiguring J. C. Scott’s ‘weapons of the weak’, she argued that ‘rumours, local petitions, newspaper adverts, letters’ were more significant in ‘organising opinion and expressing opposition’, not least in interfering in the initial early processes of enclosure when opponents refused to sign bills and threatened parliamentary counter-petitions.[3]

[1] Bolton Archives, ZZ 223/6, John Albinson notebook, 1816.

[2] Bolton Archives, DDBR 5/2/2, examination of Adam Greenhaulgh, 20 August 1805.

[3] J. M. Neeson, Commoners: Common Right, Enclosure and Social Change in England, 1700-1820 (Cambridge, 1996), p.270.

The ritual of perambulation constructed a different definition of property as law. As E. P. Thompson and Everitt asserted, custom was not a ‘vague body of tradition’, but a ‘vigorous, detailed and precise corpus of local law’.[1] It was embodied in place through the performance of ritual that still meant something to local inhabitants well into the nineteenth century. Nicole Graham argues for contested ‘lawscapes’ in which inhabitants challenged the abstract geographies constructed in the legal documents and the capitalist economic geographies of agricultural improvers’ literature: ‘by refusing the universalising claims of improvement theory and the nature/culture paradigm, anti-enclosure protest and discourse locates property law, making it particular and placed’.[2]

During the enclosure of Hartshead Common/Peep Green in 1840, an enquiry into the boundary of the common heard the testimony of Abraham Horsfall, aged 76, who was ‘forty years ago a freeholder in Liversedge’, where ‘at that time he perambulated the Boundary with Liversedge people’, and he recounted the route, noting the old paths and their colloquial names, for example, ‘a party [of perambulators] went on what we call the Summer Road’, and thus conveying sense of ownership through nomination related to work practices.[3]

The enclosure of Cleckheaton and Scholes, in the heart of the Luddite Spen Valley in the West Riding, began in 1795 with the enclosure of open fields, followed by enclosure of the commons and waste passed in 1802.[4] Once the new roads were completed in early 1804, the commissioners ordered the old causeways on Scholes Green to be pulled up. The surveyor testified on 20 February:

We were stopped in our Proceedings, by a number of Persons who came when the Workmen were employed in loading and conveying the Causeway Stones in a Cart on to the new Road and would not suffer them to go forwards, but in a tumultuous and riotous manner threw up the Cart part loaded; seized it and the Horses and went to fetch Stones from oft the new Road which had been provided for making it.

Following threatening letters being sent to the commissioner, two wiredrawers, a blanketmaker and a blacksmith from Scholes were arrested for instigating the riot.[5]

[1] A. Everitt, ‘Farm Labourers’, in Thirsk, Agricultural History of England and Wales, vol iv, p.459; Thompson, Customs in Common, p.97.

[2] Nicole Graham, Lawscape: Property, Environment, Law (Abingdon, 2011), p.70.

[3] WYAS, Kirklees, KMA 929, Hartshead enclosure documents, November 1840.

[4] 42 Geo III c.45; F. Peel, Spen Valley Past and Present (Heckmondwike, 1893), p.209.

[5] WYAS, Kirklees, WYK 172/7/2, Cleckheaton enclosure papers, 1802-6.

The Sheffield Riots of 1791

Enclosure riots were not solely a rural phenomenon therefore; they occurred within industrial and semi-urban environs. They also could be within a much more complex web of grievances and political interests. The Sheffield riots of July 1791 exemplify the difficulty in determining one cause to riots of many kinds. The agitation turned both radical and loyalist directions in the heat of the moment, but maintained objectives related to deeper social and economic grievances.

The Sheffield riots illustrate conflicting notions of place and attachment to custom. They also serve as a reminder to historians that riots cannot always be classified as having a singular or clear political objective or be quantified as a singular ‘event’. Sheffield enclosure act was passed in early 1791, enclosing over 6000 acres. The greatest beneficiaries were the lord of the manor, the Duke of Norfolk, who received 1345 acres (22% of the total), and the vicar of Sheffield, Rev James Wilkinson (81 acres).[1]

Unrest broke out on 23 July, as the enclosure commissioners attempted to mark the boundaries of the new plots on Stannington and Hallam moors. Rev Wilkinson, Vincent Eyre, the town collector and steward for the Duke of Norfolk, lord of the manor, and Joseph Ward, the Master Cutler, reported that ‘considerable numbers of disorderly people’ drove the commissioners ‘from the Commons near this Town’ and ‘menaced them with the greatest personal danger if they attempt to proceed in this Inclosure and have actually burnt the farming property and broke the windows of several houses and menaced the lives and property of the freeholders friendly to the Inclosures’.[2]

Upon the arrival of Light Dragoons from Nottinghamshire on the evening of Wednesday 27 July, riots broke out in the centre of Sheffield. Crowds assembled in front of the Tontine Inn, the largest inn in the town, where the military were to have their temporary headquarters, and which was also the site where magistrates usually dispensed justice in the petty sessions. The crowd then attempted to release those imprisoned for enclosure rioting, breaking the doors and windows of the gaol on King Street and destroying the gaolkeeper’s house. The rioters moved south-west out of the town to Broom Hall, the residence of Rev Wilkinson, and ‘all his windows were broken, part of his furniture and library damaged and burnt, and eight hayricks set fire to, four of them were entirely consumed’. After being dispersed by the military, the crowd returned to Sheffield and broke the windows of Eyre’s house on Farr Gate/Norfolk Row. They were again dispersed by the military, and five men were taken into custody. Next morning, the ‘principal inhabitants’ assembled and swore in 150 special constables. During the afternoon, however, ‘the populace assembled in much greater numbers than on the preceding day and were very riotous’. Magistrates read the Riot Act and the troops and constables patrolled the town. Early in the morning of Friday 29 July, incendiaries burned the barn of the prominent solicitor James Wheat of Norwood Hall, two miles from the town.[3] Eyre, Wilkinson, Wheat, and other ‘principal inhabitants’ received threatening letters, and covert threats persisted throughout August. Eyre claimed that ‘the continued threat of arson has brought progress with the enclosure to a halt’, and the award was not enacted until 1805.[4]

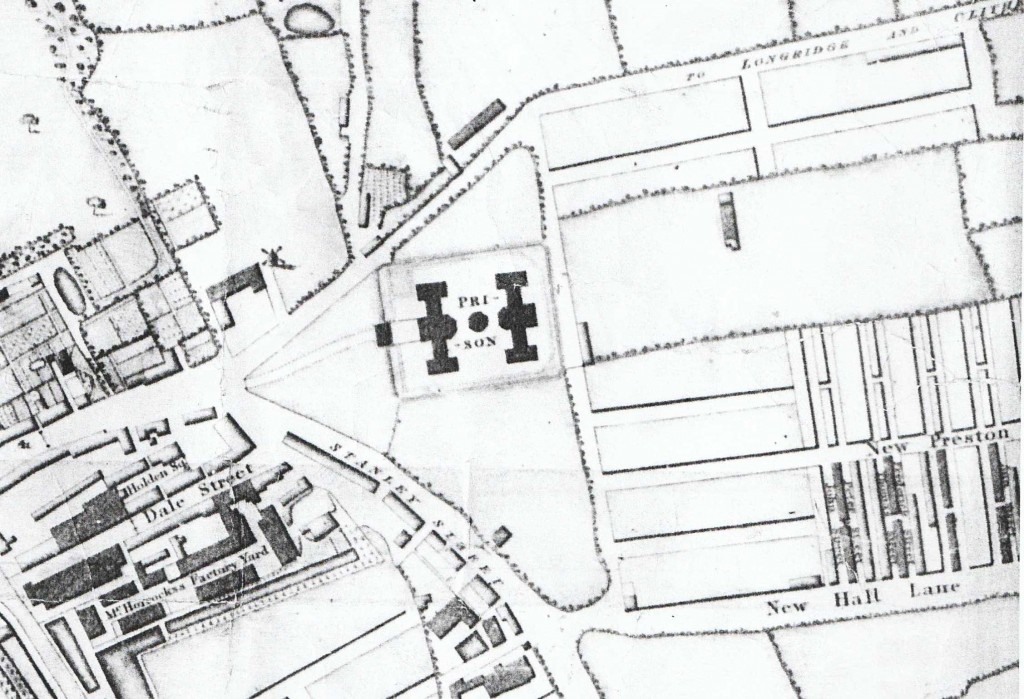

Five men were tried at York for taking part in the 27 July riots. Four were acquitted but the fifth, a John Bennet, a steel burner from the steelmaking township of Brightside Brierlow, was hanged on 6 September.[5] The others were skilled workers, including a silversmith and a collier.[6] I cannot find any record of these men being commoners of Stannington and Hallam. The July 1791 riots cost the town over £561 in compensation to injured property owners. Probably in an attempt to allay the fears of the ‘principal inhabitants’ as well as to avoid another potentially revolutionary (and indeed expensive) wave of rioting, the authorities asked the Home Office for a permanent barracks to be built. This was duly and rapidly done in August 1792. The aim on the part of the government was clear, and they authorised similar construction of barracks in Manchester and Nottingham after rioting.[7]

Historians have briefly discussed the riots as part of the older debate about whether Britain faced a revolutionary situation during the 1790s.[8] The individuals victimised by the rioters blamed the influence of Thomas Paine (who by co-incidence had only recently left the district where he had been employed to design an iron bridge at Rotherham). A letter published in the Evening Mail claimed that in response to the enclosure, ‘the lower classes of the people, both here and in the neighbourhood, are so much enraged, that their common cry is ‘Liberty or Death’.[9] Before the agitation broke out, local elites reported to the Home Office that ‘the many treasonable Inscriptions daily repeated upon walls and doors in several places in this Town for several weeks past give the Friends of Government and of the Peace of Society fear that many here are ripe for mischief’.[10] Afterwards, Vincent Eyre claimed that the agitators had shouted ‘No King,’ ‘No Taxes’, and ‘No Corn Bill’. A visitor to the town noted ‘They stuck up all over Sheffield printed bills, with the words No King in large characters. This I suppose is one mode of exerting the Rights of Man’.[11] Rev Wilkinson had been an associate of Christopher Wyvill’s Yorkshire Association in the 1780s. There was therefore a suggestion that the Paineite radicals who went on to form the Sheffield Society for Constitutional Information rejected his moderation (Wilkinson went on to inform the Lord Lieutenant Whig Earl Fitzwilliam about the SCI’s activities throughout 1792).[12]

The radical Sheffield Register however drummed up an alternative conspiracy theory – a standard classic in narratives of riots – that outside agents provocateurs were involved. It referred to the Priestley riots that occurred a fortnight previously, suggesting that the Sheffield populace had been stirred up by ‘several suspicious persons having come into the town from Birmingham, since the riots there’.[13] Eyre, Wilkinson, and Ward similarly claimed on 23 July (that is, during the enclosure riots but before the attack on their property): ‘The peaceable inhabitants of this large and populous Town and neighbourhood are under the most serious apprehensions by the very alarming Riots and Disturbances lately at Birmingham and more so from the arrival here of some of those Rioters who have industriously mixed with the disorderly people of this town’. They believed that the previous night ‘several of these Incendiaries … used strong endeavours to raise a Riot by … inviting them to bring about a Redress of Grievances as they had done at Birmingham’.[14]

Yet in this case, the targets were not Dissenters but Catholics. The Duke of Norfolk and Vincent Eyre were from recusant families, and on 27 July, the rioters ‘broke every window belonging to the house, and also the windows of the Roman Catholic chapel’.[15] So was this a Church and King riot? If so, why would they have attacked the Anglican Rev. Wilkinson? Victorian antiquarian Robert Eadon Leader noted that at the Cutlers’ Feast that year, the guild who made up much of the town’s elite ‘were almost frantic in their expression of approbation of Mr Wilkinson’.[16] His memorial still has pride of place overlooking the altar in what is now Sheffield Cathedral.

There is little indication in the assize depositions that Bennet and the other arrested men had sectarian motivations. In effect, despite the complex political situation of 1791-2, enclosure and changes to the built environment remained the central grievances. There was a longer history of claims to the common land disputed against the Duke and others. There had already been opposition to the enclosure of Eccleshall in 1788, when the occupiers of tofts and messuages felt disappointed with the small allotments given to them in compensation for their right to pasture and turn geese on the common.[17] Surveys of the Duke of Norfolk’s estates included a long list of encroachments made on the moors by his tenants. Their claims to common right were eventually rejected upon the judgement of a London barrister in April 1792.[18] Wilkinson’s hall was on the edge of the newly enclosed moor. The vicar’s burning hayricks may evoke the spectre of Captain Swing that emerged forty years later, but in this context it illustrates the wide variety of tactics, overt and overt, available to opponents of landlords’ actions. Moreover, it demonstrated the sense of place of Sheffield’s inhabitants, who remained in touch with their country surroundings and therefore with customary means of rural protest.

The riots also had roots in popular reaction against larger programmes of urban development and improvement. Eyre was Town Collector between 1790 and 1793, and was responsible for laying out the new ‘improved’ commercial and residential areas of Sheffield. He developed Norfolk’s property on Alsop Fields, and the new streets were given the family and titular names of the duke (as well as Eyre Street).[19] The vicar of Sheffield was also an active urban improver, erecting St. James Church on glebe land, and laying out Wilkinson Street and Wilkinson Lane on the southern edge of newly enclosed Crookes moor.[20] The naming of the streets were obvious acts imposing symbolic ownership of the new spaces. Popular memory and attachment to place also appear to have played a part. Leader suggested that the attack on Rev Wilkinson stemmed from inhabitants’ resentment against the widening of Church Lane in 1785. The improvement took a strip off the graveyard, leading to ‘serious commotions’ among local people whose relatives were buried there. Popular feelings about the change were clearly still raw six years later. The prolific radical poet and balladeer Joseph Mather composed the gothic song ‘The Black Resurrection’ in response. Mather envisaged a man risen from the dead because of the removal of his grave, who bitterly castigates the vicar as an ‘old serpent’:

Thus raised by his infernal power

I went the old ruins to view,

I saw in the course of an hour

Wide streets and high buildings all new,

And heard a lamentable cry

Of many a serpent-stung friend,

Whose all had been sacrificed by

That black diabolical friend’.[21]

Mather’s comment about the ‘wide streets and high buildings all new’ suggests a sense of anger at unthinking urban improvement which disrupted inhabitants’ sense of place engendered by memory and custom. Embodied place again, like the cholera riots in the 1830s. As most of Mather’s other songs were political if not Paineite radical in subject matter, there could have been a shared sense among radicals about such broader incidents of removal of inhabitants’ rights to place, although this was a line of thought shared more generally among non-radicals.

[1] Sheffield Archives, ACM/S/ 70, Sheffield enclosure award, 1805; http://www.sheffieldindexers.com/Memories/CherishedMemories_InclosureAwards.htm#Sheffield

[2] TNA, HO 42/91/256, Wilkinson, Eyre, and Ward to Dundas, 23 July 1791.

[3] Sheffield Register, 29 July 1791; TNA, HO 42/91/294, 296, 354, 537, Eyre to Dundas, 29, 30 and 31 July,25 August 1791; E.A. Smith, Whig Principles and Party Politics: Earl Fitzwilliam and the Whig Party (Manchester, 1975), p. 131.

[4] TNA, HO 42/91/537, Eyre to Dundas, 25 August 1791.

[5] William Knipe, Criminal Chronology of York Castle (York, 1867), p. 110. Bennet’s deposition at the assizes is in TNA, ASSI 45/37/2/8, examination of 30 July 1791, although he signed his name ‘John Bennitt’.

[6] TNA, ASSI 45/37/2/51-53, York assizes depositions, 30 July 1791.

[7] TNA, HO 42/20/528-537, papers of Col. De Lancey, August 1792.

[8] John Stevenson, Artisans and Democrats, (), p. 47; John Stevenson, ‘Sheffield and the French Revolution’, in David Williams, 1789: the Long and the Short of It (); F. K. Donnelly and J. L. Baxter, ‘Sheffield and the English Revolutionary Tradition, 1791-1800’, IRSH, 20 (1975).

[9] Evening Mail, 29 July 1791.

[10] TNA, HO 42/91/265, Wilkinson, Eyre, and Ward to Dundas, 23 July 1791.

[11] Donnelly and Baxter, ‘Sheffield and the English Revolutionary Tradition’, 400, citing TNA, HO 42/19/354, Eyre to Dundas, 31 July 1791, and Manchester Archives, M35/2/44/41, Barker to Worsley, 29 July 1791. Smith, Whig Principles, p. 131.

[12] J. Wrigley, ‘James Montgomery and the Sheffield Iris, 1792-1815’, Transactions of the Hunter Archaeological Society, 10: 3 (1975), 173.

[13] Sheffield Register, 29 July 1791.

[14] TNA, HO 42/91/256, Eyre to Dundas, 23 July 1791.

[15] Evening Mail, 29 July 1791.

[16] Robert Eadon Leader, Reminiscences of Old Sheffield, its Streets and its People (Sheffield, 1876), p. ?

[17] http://docs.google.com/open?id=1xErwxbyGo6qE-bmztCtKiF0DPxCF60apITz1t6vBYTEYJ8c85vV3P4VVTZRL J. S. Plant, ‘The Sheffield Plant base by around 1800’, Roots and Branches, 13, (1997), pp. 41-62.

[18] Sheffield Archives, ACM/S/466/1-10, papers on Duke of Norfolk’s claim to allotments; ACM/S/465, briefs of evidence viz Crooksmoor Common case.

[19] Richard Simmons, ‘Planning Industrial Development – the Norfolk Estate, Sheffield, 1800-1914’, Planning Perspectives, 12 (1997), 407.

[20] Joseph Hunter, Hallamshire: the History and Topography of the Parish of Sheffield (London, 1819), pp. 125-6.

[21] Robert Eadon Leader, Sheffield in the Eighteenth Century (Sheffield, 1901), p. 60; John Wilson, ed., The Songs of Joseph Mather (Sheffield, 1862), pp. 44-5.

Moving out of the small in-fill spaces of towns, radicals and trade unions found greater space and freedom in undeveloped building land and fields on the outskirts of towns. The Sheffield ‘Friends of Peace’ had held public meetings on an open piece of ground in West Street, Backfields, on the western edge of the town, in November 1793 and on the general fast day in February 1794.[1] The area was on the edge of the moors that had just been enclosed in 1791 and although Baines’s 1822 map shows that urban expansion had not yet swamped that area, the enclosure probably prevented further meetings. In December 1816, the new Sheffield radicals held meetings in a field between the Wicker and Attercliffe, on the other side of town over the river Don, and these were followed by further gatherings at an unenclosed piece of land recently purchased by the corporation to use as a burying ground. Led by a man carrying a pole topped by a loaf of bread dipped in blood, they gathered to hear news of the Spa Fields meetings in London, anxiously awaiting further instructions either from Henry Hunt on petitioning for reform, or from more radical Spencean activists on the plans for a general rising.[2] J Stuart Wortley of Wortley Hall attended with two other magistrates and ‘the whole body of special constables’ that they had sworn in that morning at the town hall. The meeting resolved to adjourn to the evening, ‘and that no women or boys should be allowed to attend’. Wortley issued a printed notice posted around the streets banning the meeting, and that all persons assembling the number of twelve or above together would be secured’. Raising two troops of yeomanry at the Wicker and a troop of Rotherham cavalry ‘at the bridge over the river Don between Sheffield and Attercliffe’, about a mile away, Wortley ensured that ‘the spot prepared for this meeting was in fact surrounded’, and thus prevented any gathering taking place.[3]

The phenomenology of meeting on such sites and their different topographies have not always been fully appreciated by historians. In Sheffield, meetings from Paradise Square and the Wicker also paraded to the Brocco. It was described in 1819 as ‘a vacant and very spacious plot of ground’, and the situation ‘admirably adapted for such a purpose; it lies on the declivity of a hill, at the bottom of which the hustings were fixed, forming a natural ampitheatre, where every individual, by being elevated above those before him, commanded a perfect view of the speakers as they successively presented themselves’. Particular sites were chosen because they were most amenable to large meetings, sometimes enabling natural amplification, and also exaggerating the visual spectacle and power of the crowd to the authorities anxiously watching from below and from the sidelines: ‘The effect now, from the bottom of the hill, became truly imposing’.

[1] TNA, TS 11/1071/5060; Proceedings of the Trial of John Horne Tooke, p. 297

[2] Sheffield Mercury, 7 December 1816; The Times, 9 December 1816.

[3] TNA, HO 42/156/56, Wortley to Sidmouth, 12 December 1816.

Rural incendiarism

Steve Poole argues that the tensions inherent in rural incendiarism cannot always be categorized along simple labourer versus landowner class lines. While incendiarism may indeed have been used against tithe collectors, land–grabbing landlords, and advocates of enclosure, it could also cut through the faultlines of this two class dichotomy, instead being used an ‘optional weapon in multi-causal conflicts between large and small farmers, warring local families, potato thieves and market gardeners, licensed and unlicensed publicans or sacked workers and their employers’.[1]

There were certainly wider factors in play, together with the use of multiple anonymous tactics. Sir George Wombwell’s estate at Newborough was attacked three times, but significantly these attacks were accompanied by animal maiming. Wombwell had gained the estate by his wife’s inheritance in 1825. He had been praised by the Yorkshire Gazette for his rent reductions and generous allocations of cow gates and potato gardens and for his wife’s philanthropic efforts for the poor of the estate. But he was also an absentee landlord of a closed village, and his estates were frequently targets for poachers.[2] His tenant farmers were unpopular and thus proved to be the main targets, feelings indicated by the maiming of their animals. On 29 December 1830, the cartshed of John Buckle of Newborough was burned, and his cattle had already been maimed by a labourer who had been sent to the House of Correction. Another labourer, Francis Burnett, aged 24, was committed to trial on 31 January for having maimed another of Buckle’s calfs, although he was discharged for lack of evidence. George Cussons, another tenant farmer, saw all his barley fired in January 1832. Wombwell and the Yorkshire Insurance Company offered £200 as a reward and two labourers were convicted at the assizes for incendiarism.[3]

[1] Poole, ‘A Lasting and Salutary Warning’, 164.

[2] He was also a first class cricketer…The Wombwells still live at what is know Newburgh Priory. http://www.newburghpriory.co.uk/history.htm

[3] Hastings, North Riding, p. 100; North Yorkshire Record Office, QSG, calendar of prisoners Northallerton 1790-1803 House of Correction 1813, 1817-99

General QS 4 April 1831; Yorkshire Gazette, 19 February, 2 April 1831, 14 January 1832.

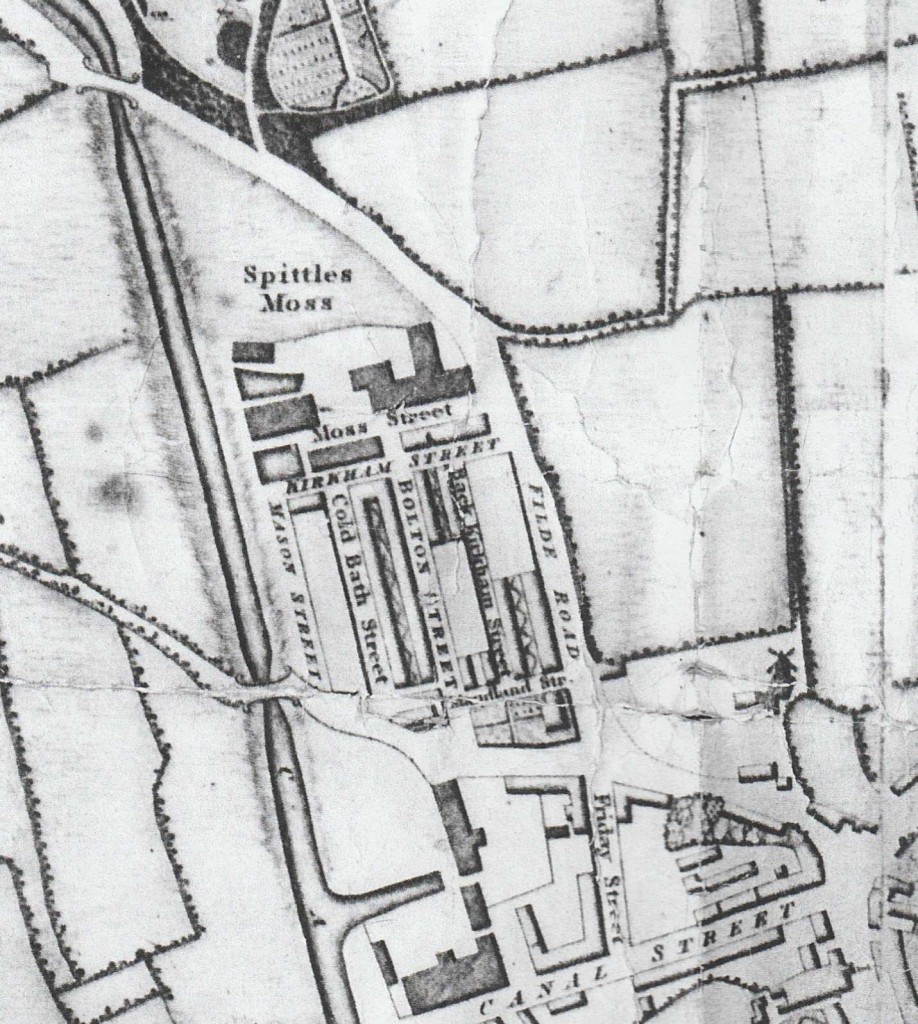

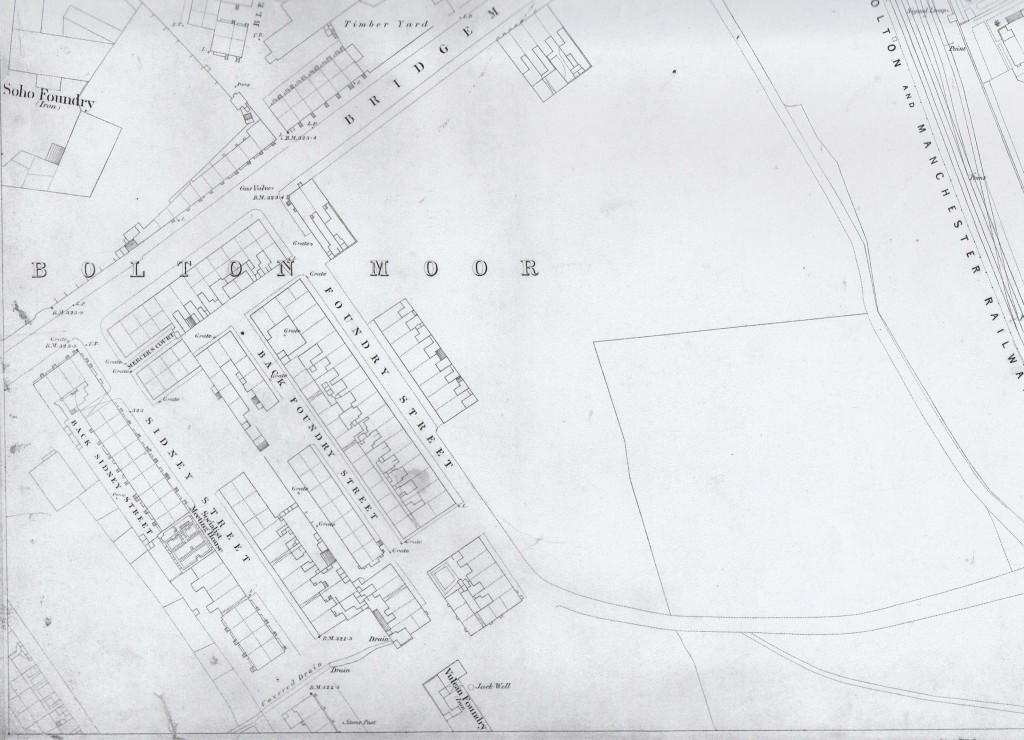

New terraced housing for factory workers, and canals:

Outlying settlements:

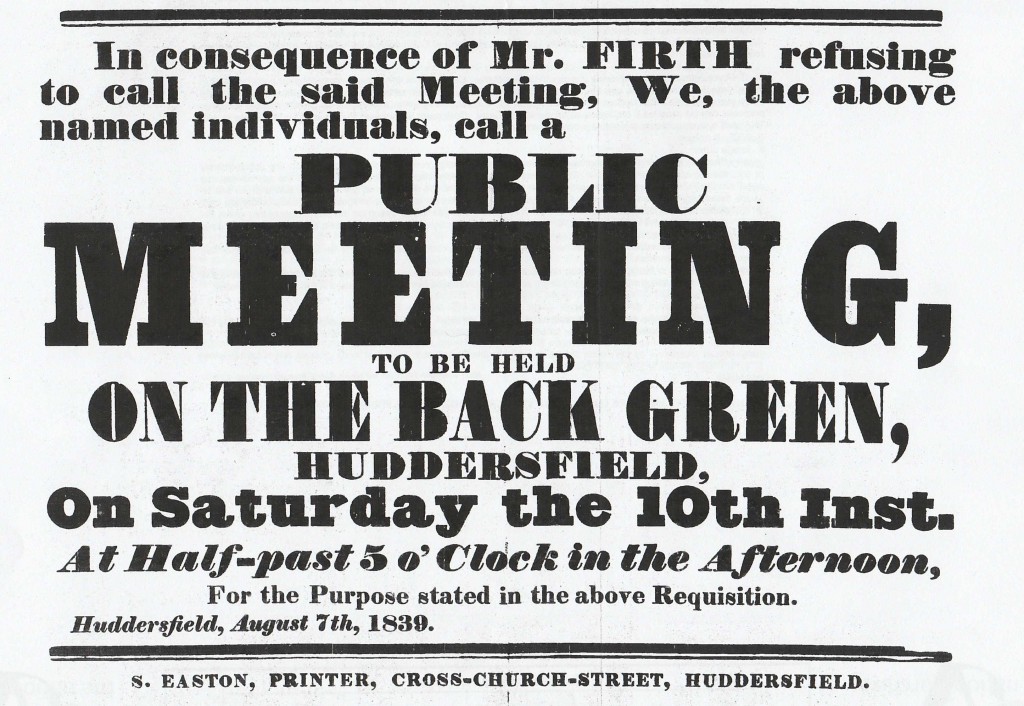

Outlying settlements were also a different type of edgeland. Caldewgate in Carlisle in Cumberland, Almondbury outside Huddersfield and Wibsey Low Moor outside Bradford in the West Riding, the industrial settlement of Charlestown outside Ashton-under-Lyne and the village of Royton in Lancashire, and the rapidly expanding townships along the Tame Valley on the border with Cheshire shared particular characteristics. These were ‘neighbourhoods’ with a mixed ethnic and immigrant population largely involved in the volatile textile trades and mining, on the outskirts of a town centre and thus to some extent independent of elite control or surveillance, but near major routes of communication with similar communities in other towns. These were distinctively outlier places that fostered continuity in political and religious dissent and a strong sense of trade and community independence. Working-men’s clubs, Chartist rooms and radical religious sects seem to have been more active in these places than in their nearest towns.[1]

[1] Oldham Archives, William Rowbottom diaries; Northern Star, 17 February 1838, 9 May 1839.

The outlying districts of towns offered a more hospitable and easily accessible (and indeed more private out of the intruding eyes of the authorities) site for radical and working-class collective activity and meeting. By the 1830s, urban in-filling and expansion had caught up with townships and villages that had previously been separated by stretches of countryside or scrubland.

Yet the sense of separation and no-man’s land remained, and fostered a sense of independence and militancy in these areas. Some of these villages and townships had long histories of radicalism and collective action. The villages and townships around Ashton-under-Lyne, for example, which had fostered Unitarian and millenarian congregations and radical political groups since the French Wars, offered their residents a local alternative to travelling to Ashton for organisation or meetings.[1]

The population of the formerly agricultural and weaving township of Dukinfield, on the border of Lancashire and Cheshire, had one of the largest percentage population increases in the whole of northern England: from around 1700 in 1801 to over 22,000 in 1841, the majority of whom were cotton workers employed in the factories along the river Tame. Yet the spirit of independence that its former Unitarian lord of the manor Sir Francis Dukinfield Astley had promoted in the earlier period, was maintained in this much larger community. Dukinfield produced its own radical association, which opened their own association room in March 1838, described as ‘a very commodious one, centrally situated, and is furnished with the Northern Star’.[2]

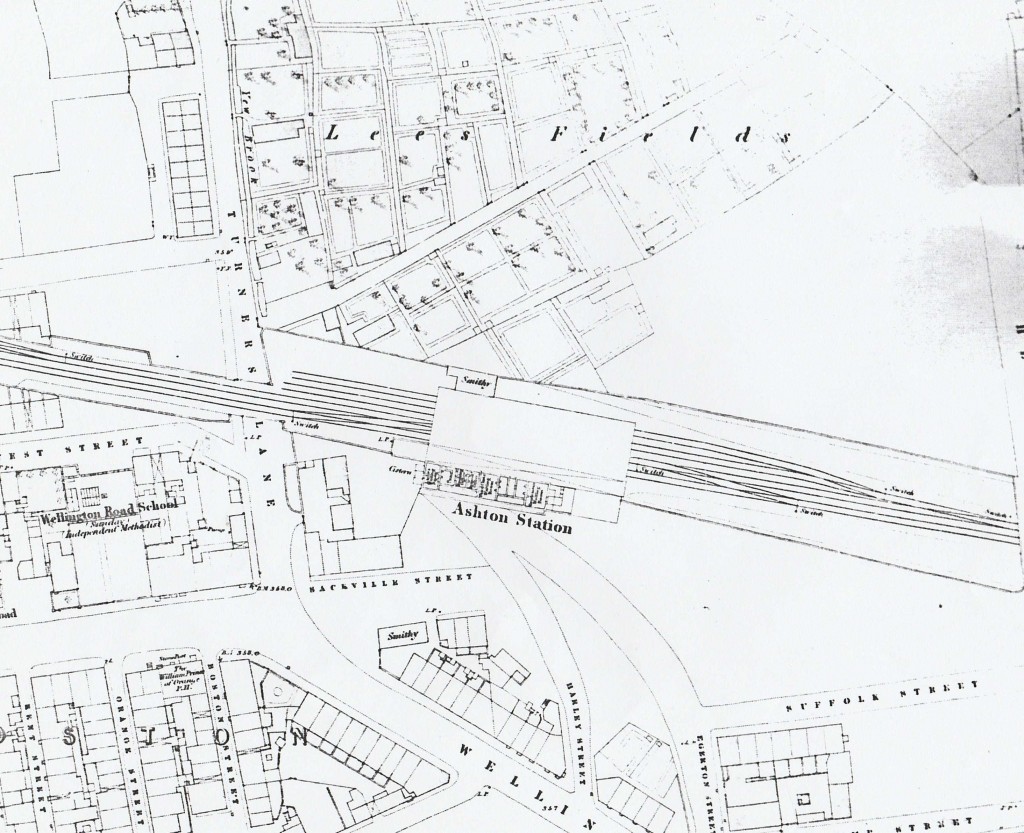

Ashton-under-Lyne and its ‘satellite’ industrial community, Charlestown, Lancashire, in Baines’s 1824 map:

Charlestown, the planned industrial settlement just north of Ashton, similarly fostered a long radical tradition that translated easily into the quick uptake of Chartism as well as active trades unionism among other movements. Female radicalism offered an educational sphere which was more informal and neighbour-based than the official meetings. The Chartist weaver and schoolmaster William Aitken of Ashton-under-Lyne recalled that his ‘earliest remembrances of taking part in Radicalism are the invitations I used to receive to be at ‘Owd Nancy Clayton’s’ in Charlestown on the 16th of August to denounce the Peterloo Massacre and drink in solemn silence to the ‘immortal memory of Henry Hunt’.[3] Clayton and her husband were Peterloo veterans and, as was an integral part of Chartist political formation, shaped collective memory of the massacre as a cornerstone of their own beliefs and to inform the new generation. It is significant that they were part of the artisan and weaving community of Charlestown. Hence this sort of familial, inter-generational radicalism easily took root in small satellites of industrial towns, such as Charlestown, Caldewgate in Carlisle and Almondbury in Huddersfield.

So domestic spaces such as ‘Owd Nancy Clayton’s’ were more familiar to the close-knit communities and were centres of political education and informal meeting. Aitken also gave an insight into Clayton’s defiance of authority, as she used her black petticoat worn to Peterloo as a flag, which she provocatively hung out of the window, together with a green cap of liberty. On 16 August 1838, the magistrates of Ashton-under-Lyne ordered special constables to confiscate these symbolic relics, but the women of Charlestown found out and ‘drew them in from the window and hid them’. The chief constable ordered a search of the house and confiscated the flag from under the bed.[4] They intruded into her domestic space, under the Six Acts’ prohibition of political emblems. The Northern Star boasted in December 1841 that ‘since Mr O’Connor’s visit to the town, the members of the NCA have increased to such a degree that their room in Catharine Street has become too small to hold them’, and so they took ‘a very large and commodious room in the Old Factory, Wellington Road, Charlestown’.[5]

[2] Northern Star, 24 March 1838.

[3] Ashton Reporter, 30 January 1869, cited in Dorothy Thompson, Outsiders: Class, Gender and Nation (London, 1993), p.84; Epstein, Radical Expression, pp.147-8.

[4] Thompson, Outsiders, p.85.

[5] Northern Star, 24 December 1841.

First edition OS map, 1852: (George Street going north on the eastern side of Baines’s map now meets the new Wellington Road):

When you look at stuff like this, it makes you grateful, but also reminds us that in many respects, we haven’t really moved on, have we?

https://youtu.be/hDG_hl_qZKw