Political Meetings Mapper:

I have mapped all Chartist meetings and lecture tours advertised in the Northern Star, 1841-44, for my winning entry to the British Library Labs competition, 2015: the website is http://politicalmeetingsmapper.co.uk

This is an original research article: please cite as K. Navickas, ‘New Political Sites of Meeting in the 1830s and 40s’, http://protesthistory.org.uk/halls-meeting-rooms

Chartist challenges over civic sites

Chartist opinions were increasingly represented in matters relating to civic patriotism, reversing the exclusion that working-class radicals experienced since the 1790s. This was achieved through sheer persistence and forthright challenges.

At Hull in December 1840, the mayor held a meeting in the town hall at eleven o’clock in the morning to draw up an address to the Queen, congratulating her on the birth of her daughter. Attendance was low, and Mr Healey, ‘a working man’, objected to the ‘unreasonable hour for which it was called, as it excluded almost all the working classes’. The meeting was adjourned to a Friday evening, and a committee was formed with the Chartists, Whigs and Tories having three members each. Again this indicated that the local elites had to take the Chartists if not seriously then at least on the same grounds as the other parties. The Chartists used the opportunity to bring up their other grievances, asking rhetorically, ‘if there are not 200,000 handloom weavers in a state of destitution? … Do we not see Union bastilles erected all over the country, and have they not inflicted upon the country a Rural Police force to mark the footsteps of the working classes, and to transmit to the Secretary of State every circumstance connected with their movements?’[1]

The mayor of Stockport had given his consent for Chartists to use the Court Room in December 1838, but when placards appeared announcing the purpose of the meeting was to elect a delegate to the National Convention, he withdrew his consent and the Chartists had to meet in the much smaller Association Room.[2]

In January 1841, the Northern Star reported that in Wigan, ‘for the first time in the history of this town, the working classes have had the use of the largest room in the place, namely, the Commercial Hall’ in support of the imprisoned Chartist leaders Frost, Williams and Jones.[3] The Chartists had previously attempted to use the Commercial Hall for a large meeting to support the Convention on 25 June 1839, but were forced to use the marketplace because, as the Northern Star alleged, ‘the shopocracy, who have possession of that place, on second consideration, determined not to allow the people to meet there’.[4] The paper thus repeated its common suspicion of the lower middle classes, whom they blamed for valorizing the exchange value of buildings rather than their use, and for weakening their cause by following the Anti-Corn Law League.

[1] Northern Star, 12 December 1840.

[2] TNA, HO 40/36/143, 145, 148, Pendlebury to Leach, 5 December 1838.

[3] Northern Star, 9 January 1841.

[4] Northern Star, 6 July 1839.

Market sites

The emergence of the grand Victorian covered market offered large spaces that were sheltered from the rain and smaller offices for committee meetings (and controlled by commercial interests more concerned about income than about the potential problems of allowing political meetings on their premises).

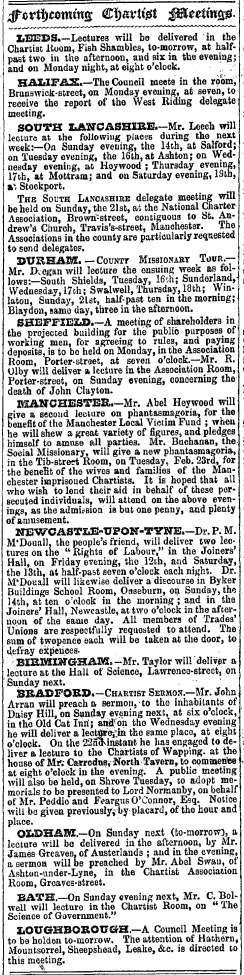

Leeds Chartists hired a room in the fish market, part of the Bazaar and New Shambles, funded by shareholder subscriptions in 1826. The main bazaar was an impressive 219 feet long, lit from the top, with a grand entrance portico of Tuscan pillars. The fish market was situated at the eastern end, and featured stone pillars taken from the old market cross on Headrow after its demolition.[1] The ‘Northern Union Room’ or ‘Association Room’ was in operation from autumn 1839, including meetings to elect radical members onto Leeds corporation, and a series of lectures to assist Bronterre O’Brien to establish the Southern Star newspaper. It was the Chartist headquarters during the election of June 1841.[2] It was the venue for the formation of the Women’s Radical Association on the evening of Tuesday 1 October 1839.[3]

The New Cross branch of Manchester Chartists took a former cheese room in Smithfield market, which subsequently served Richard Carlile as a radical chapel and then became an educational institution and then a temperance hall.[4] Smithfield was in the vicinity of New Cross and near to traditional heartland of radicalism in Ancoats – interestingly unlike in other towns, the lord of the manor desperately clung on to control – Sir Oswald Mosley refused a meeting of ‘the unemployed’ at the market in December 1842, which had to be adjourned up the road at St. George’s Fields, but after incorporation, with the loss of the lord of the manor’s control over the markets, the Chartists regularly held public meetings at the market during their last push for the Charter in 1848.[5]

Chartists in Halifax met in the Bazaar in March and April 1848.

[1] Annals of York, Leeds, Bradford, p. 300.

[2] Northern Star, 5 and 26 October 1839, 26 June 1841.

[3] Northern Star, 5 October 1839.

[4] Pickering, Chartism and the Chartists, p. 31; Champion, 18 November 1838.

[5] Manchester Guardian, 3 May 1843; TNA, TS 11/137/374, trials, 1848

Spaces for alternative education, economy and entertainment

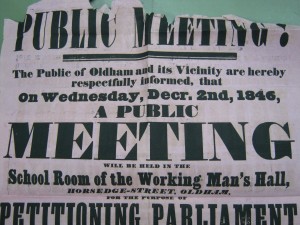

Prohibited from meeting in town halls and other civic sites, political movements hired and then began to build their own sites.

Owenite socialists, Chartists, trades unions and the other social movements that emerged in the 1830s hired or constructed detached buildings for their sole use. These sites of meeting functioned not just for immediate campaigns, but for longer visionary goals. These were spaces to enact an alternative economy, a freer religion, an egalitarian education and for entertainment.

Association rooms, working-men’s clubs and halls of science reflected a holistic view of how politics should shape communities and their everyday life. They offered a new definition of public space.

Education of children in politics, a concept that harked back to Catharine Macaulay and Mary Wollstonecraft, was the objective of female radical groups. The Elland Female Radical Association resolved at its foundation in March 1838 that ‘females in all ages have been the best advocates for liberty; for we give the first impulse in forming the infant mind’, and thus they sought ‘to give and receive instruction in political knowledge and to co-operate with our husbands and sons in their great work of regeneration’.[1]

[1] Northern Star, 24 March 1838; Chase, Chartism, p.28.

Map of meetings in halls of science, socialist halls, working men’s halls and radical rooms:

Owenite socialists used halls of science to challenge the dominant political economy of the elites and offered an alternative to the middle-class controlled mechanics’ institutes. Through the conviviality and mutuality of working men’s halls, the trades unions provided an alternative to the drudgery of factory work. The Chartists attempted to create a holistic way of life with entertainments, shopping and education in their own halls, shops, chapels and schools. The more radical Dissenting sects continued to look to this world and the next against the alienating class hierarchies of Anglican churches and the increasing conservatism of traditional Methodism.

In the Oldham socialist room in Albion Inn yard, almost as soon as it had opened in October 1841, the lecturer Mr Campbell of Stockport ‘delivered an address recommendatory of the building of a Hall of Science in shares of £1 each’.[1] So as soon as the socialists had found somewhere to meet, they immediately looked forwards to a new type of site.

[1] Oldham Archives, D-BUT F/75, Butterworth news reports, 1841.

Halls of Science

Halls of Science were constructed by Owenite socialists in the 1840s, partly to offer education for the working classes, but more generally as part of their utopian vision of building a new community.

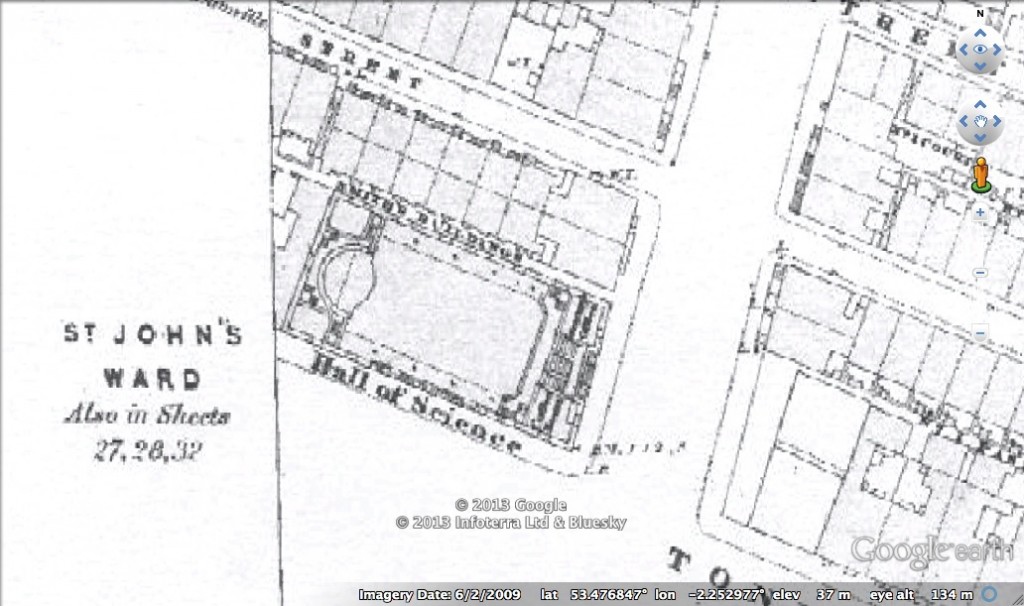

Zoom in to the first edition OS map (sheet 33) c.1849 to see the Hall of Science, just next to where the museum of science and industry now stands.

Owenite socialists sought a new truth that challenged the individualistic profit-motive of the developing ‘Manchester School’ of laissez-faire merchants and manufacturers, as demonstrated by their Free Trade Hall.

The main spaces within the new socialist and Chartist halls were designed around large lecture rooms and schoolrooms used for Sunday and evening schools, for adults as well as children. These were not just alternatives to but in direct opposition to the middle-class provision of education and religious teaching. Radicals believed that mechanics’ institutes taught a singularly technical curriculum fit only to make workers into controllable and efficient cogs within the industrial economy, as well as perpetuating a governance dominated by employers and upper-class subscribers as a form of paternalistic philanthropy.

These buildings were not intended as subversive statements, but rather as positive alternatives to the limited options available to the working classes.

Halls of Science and other new political meeting rooms were often built on the edgelands of towns, where building land was cheaper and more available.

Raising money and organizing the building of these new sites was in itself a political act. In the Oldham socialist room in Albion Inn yard, almost as soon as it had opened in October 1841, the lecturer Mr Campbell of Stockport ‘delivered an address recommendatory of the building of a Hall of Science in shares of £1 each’.[1] So as soon as the socialists had found somewhere to meet, they immediately looked forwards to a new type of site. Many groups sought to break their reliance on renting and the insecurities it entailed, as well as the issue of using hard-earned rent to line the pockets of rackmanish landlords, and followed their much bigger ambition to finance and construct their own buildings. The significant capital needed to build such sites was raised by share clubs and building societies. The halls of science in Manchester (a cost of £6000), Halifax and Stockport were financed in this way.[2]

Owenites in Liverpool formed a joint stock company to build their hall of science in Lord Nelson Street, and 148 subscribers took up 680 shares at a nominal value of £6 10s. The investments reflected the confidence in their success and longevity as well as a strong tradition of building societies as a form of mutual self-help and alternative economy (although more individualistic than strict Owenite economists would have liked in theory). John Finch (1784-1857), a successful iron merchant and member of Renshaw Street Unitarian Chapel (nearby) was the leading figure in promoting the construction of the Hall of Science in Liverpool. Finch had already planned a co-operative hostel for seamen with a savings bank, library, school and lecture rooms, and the name of his first Owenite society in 1832 was (as well as being the longest name for a society ever) indication of his committed utopian vision: the ‘Institution of the Intelligent and Well Disposed of the Industrious Classes for the Removal of Ignorance and Poverty by Means of Education and Employment, and for Promoting Union and Kindly Feelings Among All Ranks, Sects and Parties’. Finch also became a trustee and later governor of the Owenite communitarian experiment of Harmony Hall.[3]

The construction of the halls was faced with local opposition, and in Huddersfield for example, the Owenites faced difficulties securing the land for their hall, as almost all the land in the town belonged to the loyalist Anglican Ramsden family. They succeeded in completing the hall (in the ‘Bath Buildings’, Newhouse) in November 1839. Feargus O’Connor lectured to 1500 in the hall in aid of John Frost’s defence fund in the opening month, and Chartists continued to meet in the council room in the early 1840s.[4]

[1] Oldham Archives, Butterworth diaries, D-BUT F/75, Oct-Nov. 1841.

[2] Harrison, Robert Owen and the Owenites, p. 222.

[3] Harrison, Robert Owen and the Owenites, pp. 103-4.

[4] Edward Royle, ‘Owenism and the Secularist Tradition’, in Malcolm Chase and Ian Dyck, eds, Living and Learning: Essays in Honour of J. F. C. Harrison (Aldershot, 1996), p.203; New Moral World, 9 November 1839; Bradford Observer, 5 December 1839; NS, 3 August 1844.

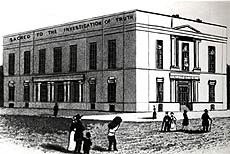

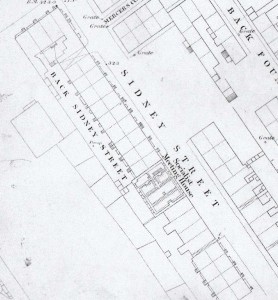

Here is the Socialists’ meeting house or hall of science in Bolton. The OS map shows how it was fairly isolated from the rest of the town, being built on the edge of the enclosed town moor to the south of the town.

Read about Huddersfield Hall of Science, whose building still exists, on Alan Brooke’s website: https://undergroundhistories.wordpress.com/huddersfield-hall-of-science/

The new buildings were a huge achievement for the political movements of the 1830s and 40s. They nevertheless ran into two problems: financial and legal insecurity, and attempts by the authorities to close them down. Working-class halls were built on financially precarious foundations. The standard one pound share was, even with the incentive of weekly instalments, a major ask of working-class supporters. The momentum waned as the movements struggled to deal with the financial and legislative problems and the sheer physical effort of organising a holistic alternative way of life in these buildings.

Nevertheless, Owenism, Chartism and other movements were able to reach the non-activist sections of the working classes more deeply and widely than their predecessors through the activities of everyday life. They offered opportunities for education, entertainment and consumption that sought to change the individual much more than occasional attendance at a mass meeting could.