- loyalist map

- Manchester: loyalist pubs

- intrusion and spies

- ‘Church and King’ violence

- list of loyalist elites

Loyalism framed a polarity between loyal and radical; it tarred all reformers with the same brush of extremism, inducing an attitude of ‘if you aren’t for us, you’re against us’. Loyalist principles and actions were as much shaped by elites’ constructed fear of this new radicalism and its potential to cause disorder among the working classes, as they were a response to actual attempts to change the political system.

Loyalism was expressed and enforced in practice by local elites creating spaces of exclusion. In the 1790s, prime minister William Pitt the Younger, his government, and indeed most governing elites, feared not merely the abstract ideas of philosophers debating the meaning of ‘liberty’, but also the emergence of working-class radical societies. Loyalist elites feared that mass collective action had revolutionary potential in Britain, especially as the Terror in France took hold. Local magistrates, clergy, mayors and other ‘principal inhabitants’ who formed the governing elite of towns were the loyalists who enforced and often went further than government repression of radicalism. They did so by seeking to exclude radicals from speaking and acting in public space, and increasingly intruding on politics in spaces regarded as ‘private’.

What John Barrell has termed ‘an atmosphere of suspicion‘ reigned in the 1790s. An atmosphere of suspicion arguably played a larger part in shaping the everyday lives of ordinary inhabitants, whether active or not in popular politics, than any edicts coming from Westminster. It involved the appropriation of civic ritual for loyalist ends. Loyalists sought to control civic and public spaces in order to exclude radical dissent in the 1790s. This process also involved defining what was constituted a public space. The atmosphere was fostered by local loyalist elites’ restrictions on political groups meeting on public sites and, more controversially, surveillance by spies into social spaces used by radicals. Though loyalists could never achieve complete hegemony over such spaces, radicals took more precautions to avoid detection, indicating that the fear of arrest shaped their actions and closed down the range of spaces in which they could meet openly.

Loyalist, patriotic and local government meetings, 1775-1815:

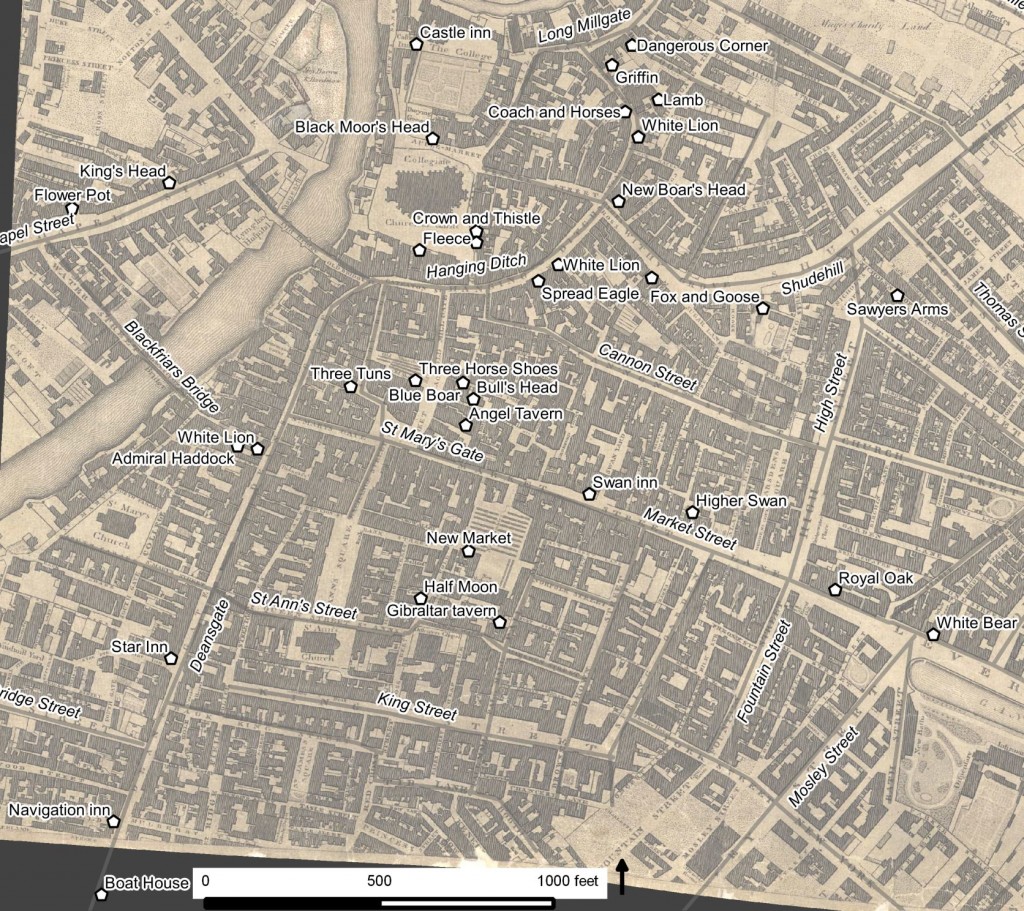

Manchester: the loyalist pubs

In Manchester, loyalists actively and to some extent successfully attempted to exclude political dissent from the ground up in reaction to radicalism. A case study of Manchester’s pubs exemplifies the closing down of arenas for discussion in the 1790s, in principle if not always achieved in practice, and the exclusion of radicals from the civic body politic.

A group of publicans held a meeting at the Bull’s Head, Manchester, on 12 September 1792. The radical Thomas Walker alleged that this was followed by ‘a tax gatherer and some other persons’ going round the town to ‘all the innkeepers and publicans, advising them, as they valued themselves, to suffer no societies to ours (the constitutional) to meet at their houses. The publicans thought their licenses of more value than our custom, and would receive neither the Constitutional, the Patriotic, nor the Reformation societies’.[1] The Manchester Constitutional Society were no longer able to meet at the Bull’s Head.

The newspapers published a list of publicans signing an address avowing they would not let radical clubs or societies to meet in their premises.[2]

The Manchester Chronicle and Oldham diarist William Rowbottom listed 228 innkeepers and victuallers signing the address. The first three pubs on the list were the biggest and most prominent in Manchester: the Bull’s Head at the top, then the Star Inn on Deansgate and the Swan Inn on Market Street; the others were also mostly clustered in the old part of town around Hanging Ditch, or along Deansgate. Most were large inns in prominent positions on main roads.[3] 228 pubs formed a relatively small proportion of the total hostelries, but the impact must have been greater in the smaller towns with fewer pubs, such as the townships around Oldham which signed the address, including Royton (7 pubs; population in 1801, circa 2700), Chadderton (7; c.3500) and Crompton (9; c.3500).[4]

The cumbersomely-named Manchester Association for Preserving Constitutional Order Against Levellers and Republicans (APCOLR) was founded on 12 December 1792 at the Bull’s Head as an umbrella institution to lead the various existing loyalist groups. Its committee included the boroughreeve and constables of Manchester, magistrates on the Salford bench, prominent merchants and manufacturers and most of the Anglican clergy from the High Tory High Anglican Collegiate Church.[5]

The committee issued a vote of thanks on 17 December 1792, ‘to the innkeepers of this Town for their laudable conduct in forbidding all seditious meetings to be held in their houses’.[6]

The publicans’ declarations cannot of course be taken as genuine evidence of complete loyalist control. Many of the pubs were listed in sequential order of location on the address. Thomas Walker made an allegation about coercion, which was probably accurate: the members of the loyalist associations must have gone round collecting signatures door to door. A face-to-face visit was likely to enforce collaboration with the address, as would the threat of a loss of their licence. During meetings to form loyal associations in late 1792, local elites in St Helens and Carlisle advised innkeepers to prevent meetings of any seditious club or society in their premises by pain of losing their licence.[7]

[1] Thomas Walker, A Review of Some of the Political Events Which Have Occurred in Manchester (Manchester, 1794), pp. 40-2.

[2] Ibid., p. 42; Craig Horner, ‘A Set of Infernal Miscreants’, Manchester Region History Review, 23.

[3] Oldham Local Studies, Rowbottom diaries; Wheeler’s Manchester Chronicle, 22 September 1792. The definite locations of 39 of these pubs can be plotted on Green’s map. The approximate location of 23 other pubs in Manchester and 15 in Salford can also be identified. Sources:1794 Green’s map, together with the 1797 Manchester Directory, 1800 Bancks’s Directory (and for the longer-surviving pubs, 1818 Pigot’s Directory and first edition OS maps). Also http://pubs-of-manchester.blogspot.co.uk/.

There are obvious problems with this approach which means that the locations of many pubs could not be identified: pubs changed their names and landlords frequently; directories were notoriously inaccurate; Green’s map only shows the largest pubs and the names of the courtyards of other pubs.

[4] E. Butterworth, Historical Sketches of Oldham, p.148.

[5] Chetham’s Library, Manchester, Mun. A.6.45, minutes of APCOLR committee, 1792-99.

[6] Manchester Mercury, 18 December 1792.

[7] Chester Courant, 1 January 1793; Cumberland Pacquet, 18 December 1792.

It was common to see pubs named after the local leading landowning family – e.g. Derby Arms, Strickland Arms, etc. There was also a trend to change the name of establishments to manifest current trends in patriotism: hence the proliferation of ‘Admiral Nelsons’ and ‘Duke of Wellingtons’ after 1815.

Later in this period, some pubs were able to name themselves overtly after their political preferences. James Vernon notes how during Henry Vincent’s tour of Lancashire in 1838, the Chartist orator was ‘amazed at the intensity of radical opinions’ which he gleaned from the ‘numerous public house signs’: ‘full length portraits of Hunt holding in his hands scrawls [sic] containing the words Universal Suffrage, Annual Parliaments, and the Ballot. Paine and Cobbett also figure occasionally’.[1] An O’Connell’s Arms opened in honour of the Irish repeal leader on Oldham Road, near the Irish districts of Manchester, in 1836. In nearby Great Ancoats, the old Spinners’ Arms was renamed the Lord Brougham in 1834 to celebrate the Whig leader.[2]

Nevertheless, most pubs were not so overt: publicans were anxious both to keep their licences and to appeal to as many patrons as commercially possible. Though the Spinners Arms or the Bishop Blaize reflected community and trade identities in cotton and woollen districts respectively, drinkers were usually likely to pop into the Red Lion, the Swan, or other such commonly named establishment, without thought for any political nomenclature.

[1] James Vernon, Politics and the People, p. 215.

[2] Robert Magee, Pubs of Ancoats, p. 32.

Intrusion and spies

Magistrates resorted first to policing working-class radicalism through intrusion into private spaces through complex but fickle networks of spies attempting to infiltrate radical groups. Initially the General Postmaster attempted to recruit informers from within radical ranks, including Joseph Gales of Sheffield, but with their obvious refusal, magistrates relied on a motley crew of mercenary individuals.[1] With their tendency to exaggerate in the hope of more commissions, however, the Home Secretaries often expressed their unease at having to shell out ever more money for ‘A’, ‘AB’, ‘C’ and the other spies employed by Colonel Ralph Fletcher of Bolton, William Chippendale of Oldham and other active magistrates throughout the 1790s and 1800s.[2] The Treasury Solicitor also employed local solicitors to act as agents in the provinces.

The loyalist purpose of these men was evident in their role as committee members of loyal associations in Manchester, Warrington, Halifax, Chester, and Stockport. The Chester agent claimed that the loyal association ‘had the good effect of stopping the sale of Paine’s works … and a seditious meeting was immediately dispersed’.[3] However, such surveillance rarely led to mass suppression or even to any action at all. The information provided by spies was too diffuse to be acted upon. The chairman of the loyal association in Selby, West Riding, admitted that although they had information about ‘a set of men in a neighbouring village’ who were attempting to ‘disaffect the minds of their Peaceful neighbours’, unfortunately ‘this information is not thought sufficiently strong to proceed upon’. The committee acted ‘with the greatest caution’ because they feared ‘the bad consequences which wou’d attend a Prosecution and failure in conviction’.[4]

It was difficult for the authorities to prosecute for sedition alleged to have taken place in more private arenas. Some rank-and-file radicals were charged with ‘uttering seditious words’ in pubs, although it is difficult to quantify how many. Few were brought to the quarterly assizes, as a trial required many witnesses and evidence, although more may have been brought in front of the weekly petty sessions but records for these (often held in a pub) are brief or incomplete. A Preston magistrate brought the case of George Latus, a husbandman from Myerscough, a village about eight miles north of Preston, to the assizes in March 1794 upon the information of a publican that he had drunk the toast ‘Liberty, Equality and the King behind’. Whether Latus intended the words, which indeed could be interpreted in several ways, or the fact he was drunk when he gave the toast, was irrelevant in the view of the court to his guilt.[1]

[1] TNA, HO 42/29/116, Shuttleworth to Home Office, 19 March 1794.

In November 1795, Johnson Atkinson Busfeild, magistrate in Bingley, questioned James Shaw, a shoemaker and ‘disciple of [John] Thelwall’ who had been sent up from London, but discharged him with a warning for lack of evidence. Shaw continued to give political lectures round the West Riding, and then resurfaced in the authorities’ radar in spring 1798, this time over the Pennines in Manchester. He allegedly helped to found a new Manchester corresponding society and, together with Thomas Walker, organised a large reform meeting at St John’s churchyard (Camp Field) off Deansgate, near to where Shaw lived.[1]

[1] TNA, HO 42/36/284, Busfeild to Home Office, 9 November 1795; HO 42/45/528, examination of James Dixon, 5 May 1798.

‘Church and King’ violence against radicals

Here is a transcribed report of the ‘Royton Races’, an attack on the ‘Jacobin Library’ at the Light Horseman pub, Royton, Lancs, in 1794:

Lancashire County Record Office, DDX 351/1-2 – depositions of George Shaw of Gorton Hall on the Royton races, 1794:

1 – I set out from home on Monday morning last (April 1794) to go to Royton in company with G.J. of L, J.L. of L. and several others, calld on Wm J of D – arrived at Royton betwixt 10 and 11 o’clock when we came to the chapel a man said he wou’d conduct us to a public house where we would be well used he tooke us to the Light Horsman we had not been there long before a great many people assembled before the Door in a Rude Manner pushing one agent another of any person went out of the house the were cicked and ill abused we seeing them behave in so riotous a manner we thought it best to get home as peaceably as we could so we concluded to go down staires in a boddy through the Landlords Garden when I was got over the garden edge I set of runninf I had not come above half way over the field befour I was knocked down by some persons who kicked me so long that I could with difficulty get my breadth when I got up, when I had recovered myself a little I set a running again as well as I could and before I got to the Brook at the bottom of the field I was overtaken by severall others when as I attempted to get over the Brook knocked me into it and when I got up I maid an attempt to get from them, they abused me very much, when I could not get up the side of the Brook, from then I offered to go up the Brook – the knocked me down in a Deep pool of water in the Brook which I expected to be drowned in, when I had got out some persons said Damn him in him with he has not got pistols whith that the got me down again and took a pistol out of my right inside coat packed and the tooke me up to Mr Pickfords at Royhton as the were taicking me up to Mr Pickfords some person or persons tore my Coate off my Back…when I caime into the yard I saw G.J. of L and J.L. of L both prisoners when I got into the yard I was verry glad as I expected nothing but Immediat Death from the Mob – the put us into the stable and kept us there five or Six hours while were in the stable we were insulted by the ? in very much we were examined before Justice Drake and Hantwistle when the examined the Whitness against me that tooke the pistol out of my pocket he said he took it out of my right waistcoat pocket I said it was in my right coat pocket. I was asked what maid me come to Royton I said by seeing a hand bill I was asked where I saw it I said Mrs Travis gave me one. I was took into Mr Pickfords Kitchin when G.J. and J.I. was when we had been ther some time we were tied together two and two G.J. of L. and myself – were tied together we were took in that posture to Rochdale attended by severall constables and soldiers drumming and fifing all the way when we arrived at Rochdale G.J. and myself were confined at the Spread Eagle when we arrived in the lock up roome we had the handcuffs put on when the brought us our supper the constable tooke the handcuffs off and we had them put on no more that Night we were attended all Night by Two Soldiers who were locked up with us – we were took before the Justices Drake and Hantwistle, I was inducted back to the Spreadeagle, the constable come to G and M, and told us if we would pay for a chaise the would take us in a private m? saying when we were got out of Rochdale we might be atten’d only be the constables we were Hundrifted when we were got into the chaise the soldiers attended us with drum and fife to Manchester shouting and aranging the Minds of their Propirlay againts us, when we arrived at the New Bayley prison G and me wair put into the lockup room till about 10 or 11 o’clock when we were each of us put into separate cells and must not see each other.

/2 – extended account – [different hand and better spelling]. On Monday morning last, April 21st 1794 I left Gorton Hall, the place of my residence with G.S. of L., J.S. of do and several others to go to Royton. As we going on the road J.S. of L lent me a pistol. At Droylsden we all called on Wm.S. […same as other account]

…the constables themselves putting their heads out of the chaise, pulling of their hats and shouting huzza and thus irritating the minds of the populace against us. We were conducted through some of the principal streets of Mancr to the New Bailey prison.

[discharged]

Historians can only scratch the surface of surviving evidence for individual ‘Church and King’ attacks on radicals, especially because the very atmosphere of loyalist suspicion made victims refuse to press charges. Furthermore, the authorities not radicals determined whether attacks were ‘violent’ or not.

In June 1798, B. Roberts, member of the Liverpool King and Constitution Club, wrote a long and verbose letter to the Home Secretary Henry Dundas describing his involvement in defending loyalist principles against the ‘Jacobins’. He claimed that a radical named Highfield addressed a crowd gathered to celebrate the king’s birthday in Williamson Square in Liverpool and allegedly ‘declared himself a republican and Jacobin [and] damned K— and constitution’. Roberts noted proudly that for this action, Highfield ‘got a hearty rubbing’ and was ‘dragged to the Bridewell by a Gentleman of our Club’. He thus interpreted the attack as rough but justified treatment. For Highfield on the other hand, it was clearly brutal violence.

During the disturbances, two other radicals were arrested. The men were brought before the mayor at the Exchange the next day; the mayor ‘intimated if the parties could settle matter amongst themselves, he would allow the charge [of assault and treasonable words] to be withdrawn. Henry Brown, deputy town clerk, disagreed with this out-of-court compromise, arguing for a proper investigation, but the mayor, perhaps fearing more disorder, discharged the prisoners without bail. A ‘night of universal rejoicing’ followed on the streets, with fireworks and display of radical symbols.[5]

[1] University of North Carolina, Gales papers, ‘Recollections’, p.92.

[2] TNA, HO 42/65/481, Fletcher to King, 31 July 1802, refusing to comply with the Home Secretary’s order to diminish the number of spies; see A. Booth, ‘Reform, repression and revolution: radicalism and loyalism in the north-west of England, 1789-1830′ (PhD dissertation, Lancaster University, 1979), appendix 3.

[3] Mitchell, ‘The association movement of 1792-3’, 65, 69, citing British Library, Add MS 16924, fo.90.

[4] British Library, Add MS 16924, fo.125, Martin to Moore, 22 January 1793.

[5] TNA, HO 42/31/118, Roberts to Dundas, 11 June 1798.

List of loyalist elites in Manchester, Salford & Bolton:

(taken from K. Navickas, ‘Redefining loyalism, radicalism and regional identity: Lancashire under the threat of Napoleon, 1798-1812′, Oxford University DPhil thesis, 2005).

Love to know exactly what Rowbottom’s diaries were.

https://youtu.be/qS9XUZLGUSc