This is an original research article. Please credit if using = Citation: Katrina Navickas, ‘Processions’, http://protesthistory.org.uk/processions/processions-marches

Processions

Processions and parades were politics on the move.

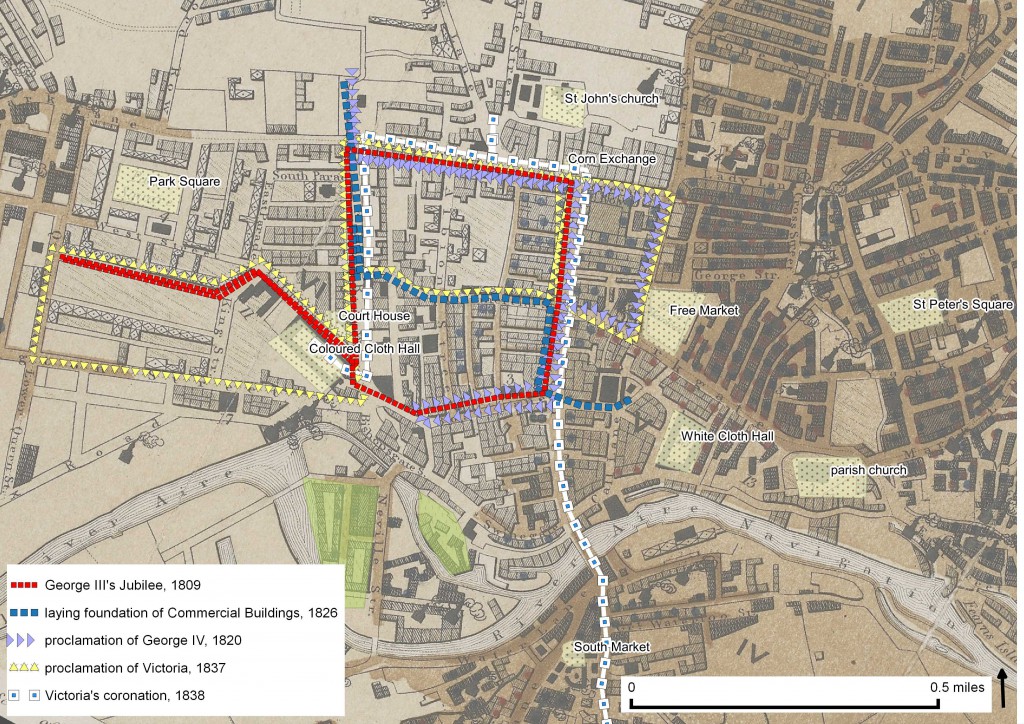

Processions were one of the central elements of popular politics in the early nineteenth century. Governing authorities and accepted corporate bodies used civic and patriotic processions to separate themselves from the inhabitants who were assigned the role of spectators, and echoed the customary practice of ‘beating the bounds’ in asserting their authority symbolically over urban space. Processions dominated civic and patriotic events that punctuated the yearly calendar of urban life. Celebrations of the king’s birthday were incomplete without a cavalcade of local notables, military and brass bands processing to and from the parish church or town hall. Civic bodies, together with freemasons and other associations, and hierarchical guilds and trades’ societies, Sunday Schools and church groups, all used the ceremonial procession to display and affirm their identity and authority. Processions were also integral to electoral politics, at the entry of candidates into a town, and chairing the Member once elected. The careful ordering of who marched where in the procession was a visual show of who was included and excluded in the civic hierarchy.

Processions demonstrated groups’ identity and solidarity as a body. Protesters used custom and ritual in bodily movements to shape a collective body. All processions, whether civic, military, electoral, trade union or radical, shared in a rich culture of symbolic expression: banners, clothing, music, mummery, and other rituals and symbols reflective of local and political identities. Custom also expressed local identities. The Pennine villages of Lancashire and the West Riding had distinctive forms of processing, most notably the practice of rushbearing at harvest time, when elaborately decorated rushcarts would be brought with much ceremony from the hills into the market towns. These different traditions and forms filtered into the processions that filled the civic and patriotic calendar celebrated in towns and villages across the country. They were especially prominent in processions and parades organised by radicals, Chartists, trade unions, and other groups in opposition to local elites.

Protesters created embodied spaces through choreography and performance, and used the body to shape new defensive spaces, as in picketing factories or loitering on the street. Trade union parading involved repetition of routes, whereas radicals tended to process from a to b, usually from political meeting room or various meetings points of different local areas to converge on ‘principal streets’ and then back out to open meeting place.

Radical and trade union processions, although in some senses similarly exclusive in their delineation of which groups could march and which order, nevertheless encouraged the crowd to challenge elite control over street space and symbolism. Radicals, trade unions and Chartists used processions to assert their collective identity as a body, challenge the routes and order established by civic elites, and gather support on their way to mass meetings.

The emergence of mass platform radicalism put processions on the centre stage of confrontational popular politics. The processions to the platform were huge, often involving thousands if not tens of thousands of participants (not including the masses of spectators). The scale of these events was so much harder to police than ever before and caused major disruption to the everyday life of the city. The route, form, and message of radical processions were the central part of demonstrations, rather than being merely an auxiliary way of getting from one place to another.

Grand entries

Another feature of the spectacle of street processions that was adapted and subverted by radicals was the grand entry. Grand entries were an established feature of electoral culture, and unrepresented areas thus mimicked electoral practice in staging their own grand entries for political figures. Grand entries confirmed the role of ‘gentleman leaders’, who were a key feature of reform movements throughout this period, bridging the local leadership of groups with connections in parliament.[1] As more radicals and independent candidates contested newly-enfranchised boroughs after 1832, the grand entry became a prominent way to mirror traditional electoral practices and command public space. It was also an opportunity to use flags and music legally after the 1819 legislation had prohibited such activity.

Welcoming leaders after their release from prison was the ultimate demonstration of the connection between movement and liberty.

This was evident at the release from prison of Joseph Hanson of Strangeways Hall, Manchester. Hanson had been imprisoned at the King’s Bench in 1808 for addressing a mass meeting of handloom weavers about their petition for a minimum wage. Upon his release in 1809, his Macclesfield supporters went five miles south on the road to meet him, taking the horses from his carriage to draw him through the town. A large body of Manchester weavers ‘went in procession from Ardwick Green as far as Stockport to meet him’, a distance of about six miles. At Stockport, Hanson was carried to the top of Manchester hill (a prominent meeting site for weavers’ demonstrations). The length of processions and length along the roads was important in demonstrating visually the extent of support for the leader. The Leeds Mercury notes that ‘the greatest assemblage … literally lined the road from Stockport and Manchester’, although Hanson did not permit himself to undertake a grand entry into his home town for fear of provoking another disturbance and his re-arrest.[2]

Henry Hunt

Henry ‘Orator’ Hunt was the head ‘gentleman leader’ in northern England, and therefore was instrumental in acting as figurehead for radical processions. He did not even need to be present for events to be organised on his behalf. On his release from prison in October 1822, in Leeds ‘the friends and admirers’ of Hunt assembled in Briggate with music and flags, and ‘marched in procession through some of the principal streets to the bonfire at Richmond Hill, which had been lighted in honour of Mr Hunt’s liberation’. A similarly scene was played out in Skipton, where the bonfires were lit in Caroline Square.

Commemorations of Peterloo had waned by 1822 but political unions revived the practice again during the push for the first reform act from 1830. Processions to and from St. Peter’s Fields, though by then more built up, linked the reformers and fight for Manchester representation with longer radical heritage using symbolic sites and ritual to revive and reshape collective memory. In Manchester in particular, it was the more radical Union of the Working Classes, rather than the moderate and middle-class political union, that took on this role. On 16 August 1830, Hunt was met at Pendleton by a band of music, and processed the two miles across Salford and Manchester to St. Peter’s Fields.[3] Hunt repeatedly visited the north from his base in London, especially from his crucial contest of Preston in December 1830 until he lost the seat two years later.[4]

Hunt’s return to Manchester on 3 May 1831 – at the height of the reform crisis – provided the occasion for another procession to bring him to St. Peter’s Fields. As usual, the crowds marked out the political map of the streets with groaning outside the officers of the both the Tory Manchester Times and the liberal Manchester Guardian, and outside Mr Birley’s house (again, touchstones of symbolism to keep alive the memory of Peterloo) before returning to the King William IV pub on Great Ancoats Street, ‘the house at which the committee of the working class’s union hold their meetings’. The route of this procession was repeated again on the anniversary of Peterloo on 16 August 1831.[5]

The effort that political unions put into the arduous task of organising such processions illustrates the importance they attached to the tactic. Hunt passed through Manchester again on his way to Preston during the election of November 1831. The Union of Working Classes responded with plans for a procession, but only 300 assembled at New Cross. They therefore sent parties out ‘in various directions in [police] districts no 1 and 2 with flags for the purpose of increasing the number’. At noon they returned to the committee head quarters, the King William IV inn, and processed the usual route to and from St. Peter’s Fields, picking Hunt up on his way from Stockport at Adrwick.[6]

On his entry into Preston on 27 December 1831, the political unions of Blackburn, Chorley and Leyland arrived in procession, assembling opposite Hunt’s lodgings in Lune Street awaiting his arrival, before processing through the main streets of the town. The next day, Hunt made a public entry into Blackburn, and the newspapers reported that ‘the people came in great numbers from all the neighbouring towns and villages and from miles along the Preston Road, the lane was completely filled with men and women’. Despite Hunt being late, ‘the multitude generally manfully stood their ground, notwithstanding the severity of the weather’.[7]

Hunt’s entry into Preston in August 1832 for the first election after the Reform Act was an elaborate affair involving the whole town and its neighbourhood. Hunt’s supporters processed ‘with flags and music’ from the Roast Beef Inn on Friargate to Walton Brow, two miles to the south, to meet him. The return procession with Hunt was headed by children and ‘probably tripled’ in size as it entered Church Street. Again customary items of electoral culture gained subversive symbolism: ‘a great number of flags and banners, amongst which were the tricolor was the most conspicuous’.[8]

[1] John Belchem and James Epstein, ‘The Nineteenth-Century Gentleman Leader Revisited’, Social History, 22: 2 (1997), 174.

[2] Leeds Mercury, 25 November 1809.

[3] Leeds Mercury, 21 August 1830.

[4] John Belchem, ‘Henry (Orator) Hunt (1773-1835)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http:///www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/14193]

[5] Manchester Times, 7 May, 20 August 1831.

[6] Manchester Times, 5 November 1831.

[7] Manchester Times, 1 January 1831.

[8] Preston Chronicle, 25 August 1832.

Chartism and the grand entry

The Chartists were the greatest exponents of the grand entry.

Their national coverage and network of famous itinerant speakers thereby gave them more opportunities to make a scene that would have wider impact. The liberation of arrested activists, especially if the Northern Star had made their cases nationally prominent, also heightened the role of the grand entry.

The Northern Star’s account of the Chartist rally in Manchester and Salford in August 1840 to welcome Peter McDouall and John Collins on their release from Chester gaol exemplified all the elements of previous oppositional processions combined into one great event. Everything was meticulously organised by different committees, and an impression of legality was paramount: ‘in order that there should be no pretence on the part of the authorities for interfering with their contemplated legal and constitutional proceedings’, delegates were deputed to wait on the head of the police, Sir Charles Shaw. The procession was headed by marshals on horseback, who wore ‘splendid green scarfs, trimmed with white, and green and white favours’, who were followed by ‘body after body … and banner after banner’.

The procession was thus highly organised and choreographed. The empty civic processions were now fully replaced and subverted by the parade of different branches of radical associations, trades groups including the Manchester Boiler Makers and the Council of the Dressers and Dyers of Manchester and Salford with a banner proclaiming ‘the Prosperity of the Working Classes is the Foundation of National Greatness’. The soundscape of civic patriotism was also subverted with odes to the gentlemen leaders: the Band of Old Forresters played ‘See the Conquering Hero Comes’ on arrival of the carriage of McDouall and Collins at Salford Crescent. Female participation, with echoes of their predecessors of 1819, was separate but distinctive, including ‘eight young women dressed in white wearing green and white favours and carrying garlands’ and the Manchester Female Radical Association near the front of the procession. Even more prominently, a carriage carrying a deputation of the Hulme Female Radical Association was driven alongside the carriage holding McDouall and Collins, and they presented the ‘patriots’ with a green scarf lined with white satin decorated with a white satin rosette, an updated version of the green caps of liberty presented to Hunt by the female radicals of 1819.

Finally, as with all Chartist processions in Manchester, the local leaders made sure to reaffirm their legitimacy and shape collective memory by overtly connecting the Chartists to the memory Peterloo. The banner of the Wigan association was inscribed with ‘To the memory of H. Hunt Esq’ and ‘O’Connor, Hunt’s successor’. The ‘operatives, six abreast’ marched with a large banner painted with a representation of the Peterloo Massacre on one side, and on the reverse, ‘Murder demands Justice’.[1] The route naturally followed the usual direction from Stevenson Square, along Oldham Street and down to St. Peter’s Field before crossing over the river to Salford to meet McDouall and Collins at Salford Crescent. The Northern Star emphasised the spectacle of the street:

The Crescent, which is a magnificent street, presented, as far as the eye could reach, a dense mass of human beings; while, as the procession went down Chapel Street, the windows, the roofs, the lamp posts, every point from which a view could be obtained, were seized upon with the greatest avidity.[2]

Salford Crescent had been built for wealthy merchants and the 1804 Manchester Guide describe it as ‘pleasant villas’ ‘upon a spot almost unrivalled for a beautiful, commanding prospect’.[3] By 1840, the area, like most former suburbs, had been choked with smoke and surrounded by working-class housing, but it maintained an ‘open and handsome’ outlook and status as one of the principal streets of the town.[4] Chartist supporters had transformed its genteel townhouses into a backdrop for their own triumph, commanding the topography of the streetscape and the views over the Irwell and Irk using the might of numbers.

[1] Northern Star, 22 August 1840; D. Thompson, The Early Chartists, pp. 139-40, 143.

[2] Northern Star, 22 August 1840.

[3] Joseph Aston, Manchester Guide (Manchester, 1804), pp. 274-5.

[4] James Bryce, Universal Gazeteer, (London, 1862), p. 550.

Lecture tours

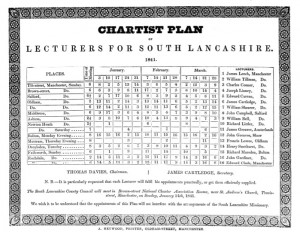

The Chartists developed a system of itinerant lecturing which they based on the Methodist circuit system of preaching.

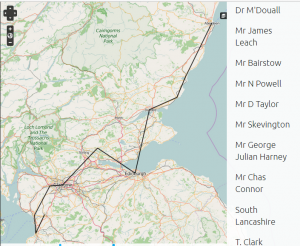

See for example this lecture plan for South Lancashire, which effectively borrows the class plan of Methodist circuits.

Janette Martin’s PhD thesis on Chartist lecturers (PDF): http://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/834/1/CORRECTEDthesis.pdf

Audiences were keen to walk an hour or so to hear a lecturer, and this served to strengthen their knowledge of and attachment to the political ‘neighbourhood’. In March 1842, for example, Bingley Chartists prepared the Mechanics Institute for an expected visit of the lecturer Mr Brophy, whose intended route had been wrongly advertised in the Northern Star. Upon his failure to arrive, they were ‘completely disappointed’, especially as ‘many persons came a distance of three or four miles to hear the lecture’, so they held a session of reading and discussion instead.[1]

[1] Northern Star, 5 March 1842.

Go to the map of Chartist lecture tours advertised in the Northern Star: http://politicalmeetingsmapper.co.uk/maps/neatline/show/lecture-tours

Go to the map of Chartist lecture tours advertised in the Northern Star: http://politicalmeetingsmapper.co.uk/maps/neatline/show/lecture-tours

The Chartist leaders spread the spectacle in their itinerant speaking tours.[1] In Leeds, the ‘liberated patriots George White, John Collins and Dr McDouall’ were met en route by women dressed in white and bearing wreaths of flowers.[2] At Ashton-under-Lyne, the Chartists organised a procession to escort him into town and offer a dinner at the Charlestown meeting house. ‘Previous to the day, the Committee for managing it waited on the authorities of Ashton and informed them of their intentions respecting the procession and dinner’.

Rumours circulated that the authorities were determined to prevent the demonstration and Mr Lord, the magistrate, ‘expressed the determination of the Magistrates to preserve the peace of the town’. McDouall’s entry was met by thousands from Ashton, Stalybridge and their surrounding villages, and the road was lined by spectators for a mile.[3]

On Christmas Day 1840, the grand entry into Manchester of the ‘liberated patriots Messrs Richardson, Butterworth, Doyle, Smith and Scott’ became a major spectacle. Chartist activists left at dawn to meet the men at Eccles, where they had breakfast. They then escorted the Chartist leaders the four miles to Manchester. The impact of this entry was amplified by the scale of the prior organization undertaken by local Chartists. Being Christmas Day, the working classes were free to participate: ‘The procession, according to announcement, formed themselves in Stephens [sic] Square at 12 o’clock. From the suburban villages, the principal streets, lanes, alleys, garrets and cellars issued persons of both sexes’.[4]

The arrival of the railways helped the most prominent Chartists to travel but they did not destroy the grand entry and traditional forms of procession. The high cost of train travel and the staggered rate of rail building meant that there was no sudden transformation. Feargus O’Connor made a triumphant visit to Bradford to celebrate his release from York gaol in August 1841. He arrived at Brighouse station by train on the Manchester-Leeds line, but then had to transfer to a coach for the last seven miles of the journey (taking an hour) for the entry into Bradford. Bradford was not connected to the rail network until the Leeds-Bradford line was opened five years later.[5]

[1] Janette Martin, ‘itinerant lecturing’ thesis.

[2] Leeds Mercury, 12 September 1840.

[3] Northern Star, 29 August 1840.

[4] Northern Star, 2 January 1841.

[5] Janette Martin, ‘Itinerant lecturing’ thesis, p. 66; D. G. Wright, The Chartist Risings in Bradford (Bradford, 1987), pp. 27-8.

Trade union marching

Parading and marching in line involved a defensive choreography, an explicit challenge to the normal uses of space. The repression of collective bargaining by the Combination Acts of 1799 and 1800 fostered among workers a sense of increased militancy. They expressed that belligerency through parading three or six abreast, using space to demonstrate the freedom to combine as well as to speak. They produced embodied space, in which their gestures and performances of solidarity charged the streets and roads in which they moved with class conflict.[1]

Parading took on more complex levels of organisation and visibility as trade unions developed in size and confidence. The first major development occurred as part of a major strike across the North West in July 1818 when cotton spinners began a campaign to reverse a large wage reduction that employers forced them to accept after the end of the Napoleonic war. The strike became a bitter struggle in which the Irishman John Doherty first proved his colours as the spinners’ union leader. Local authorities, especially those who were also industrialists, were especially concerned about the parading of the strikers because of the seemingly threatening level of organisation, particularly their military overtones.[2] James Norris, barrister and new stipendiary magistrate for Manchester, sent a long and detailed explanation of events to Home Secretary Lord Sidmouth on 29 July 1818. He first outlined the snowball effect of one trade striking after another, as the spinners inspired the bricklayers, joiners and carpenters to turn out, followed by the dyers. The dyers developed a form of protest choreography that drew on customary trade processional, but was nevertheless seen to be unusual and therefore threatening. The spinners followed suit.[3] The spy ‘B’ reported the twice–daily parades of the spinners around Piccadilly in Manchester: ‘The plan the[y] take is as follows, one man from Eich shop is chose by the People and he commands them he forms them in Ranks and attends them on the march and as the soal Command and the[y] obey him as Strickley as the armey do their Colonel and as little talking as in a Regiment’.[4] ‘B’ clearly viewed the activity within the framework of his previous experience reporting on the United English cell organization and Luddite drilling.

The trades marched in a restrained but firm manner to assert their legality and avoid arrest, to display their grievances and distress to the local inhabitants, and also to claim their right to use the streets, those symbols of the civic body politic. As the strike spread through a system of delegates, flying ‘picquets’ and the distribution of funds by committee, the authorities felt torn on how to put down the agitation. Laissez-faire and non-interference of the state in industrial relations, a principle already blessed by the government in the repeal of the statute of artificers, held some sway.[5] Norris claimed on 1 September, ‘my brother magistrates and myself did not think it right on this account to interfere in their practice in order that the lower classes might see that we kept aloof from any question between them and their employers as to the advance of wages’.[6] On 1 to 3 September, large bodies of weavers and spinners marched in military order into Manchester from the surrounding towns (following the routes that many would take to Peterloo the following year), and undertook guerrilla raids on the factories. On 4 September, the Manchester magistrates issued a public warning that they would arrest not just combinations of strikers but also anyone parading ‘down the Public Streets’.[7]

The performativity and gestures of parading hinted at the ‘mysterious brotherliness’ or ‘homosociality’ identified by historians of organised labour.[8] Indeed, during agitation in Cumberland in October 1819, when trade union and radical campaigns merged, the handloom weavers of Carlisle and the nearby village of Dalston offered a strong show of solidarity by parading ‘three abreast, and holding each others hands’ to a reform meeting.[9] Perhaps the journalist in this case mis-described the linking of arms as holding hands, but either way it was a powerful gesture of strength and unity. Parading was the default performance by trade unions, especially during the powerloom weavers’ major strike in 1826 and the spinners’ strikes of 1830-1.[10]

[1] See S. Low, ‘Embodied space(s): anthropological theories of body, space, and culture’, Space and Culture, 6:1 (2003).

[2] R. G. Hall, ‘Tyranny, work and politics: the 1818 strike wave in the English cotton district’, IRSH, 34 (1989); R. G. Kirby and A. E. Musson, The Voice of the People: John Doherty, 1798-1854 (Manchester, 1975), p.18.

[3] A. Aspinall, The Early English Trade Unions: Documents from the Home Office Papers in the Public Record Office (London, 1949), p.282; TNA, HO 42/179, Norris to Sidmouth, 29 July 1818; HO 33/2/58, Whitelock to Sidmouth, 5 September 1818.

[4] B. and J. Hammond, The Skilled Labourer, 1760-1832 (London, 1919), pp.99-100.

[5] J. A. Jaffe, Striking a Bargain: Work and Industrial Relations in England, 1815-1865 (Manchester, 2000), p.54.

[6] Aspinall, Early English Trade Unions, p.282, citing HO 42/179, Norris to Clive, 1 September 1818.

[7] Manchester Chronicle, 5 September 1818; Oldham Archives, Rowbottom diaries, 1818.

[8] Behagg, ‘Secrecy, ritual and folk violence’; K. Binfield, ‘Industrial gender: manly men and cross-dressers in the Luddite movement’, in J. Losey and W. Brewer (eds), Mapping Male Sexuality: Nineteenth-Century England (Cranbery NJ, 2000).

[9] Morning Chronicle, 15 October 1819.

[10] Manchester Guardian, 22 July 1826; TNA, HO 52/13/231, 8 January 1831.

London processions

The great processions to present the Charter to parliament were on a different scale from the civic processions in other cities and towns.

1848 Kennington Common

One thought on “processions & marches”