Original research article. To cite, please use: Katrina Navickas, ‘Oldham’, http://protesthistory.org.uk/places-maps/oldham

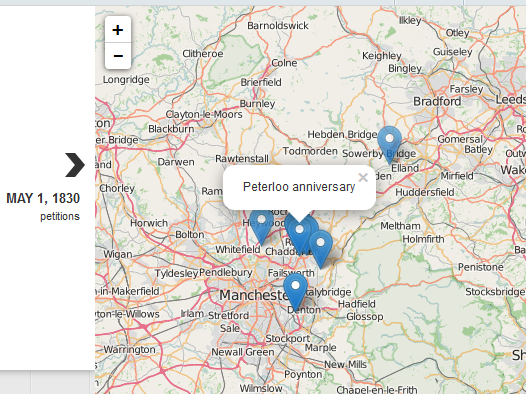

Map of political meetings in Oldham, 1792-1848:

Baines’ map of Oldham, 1823:

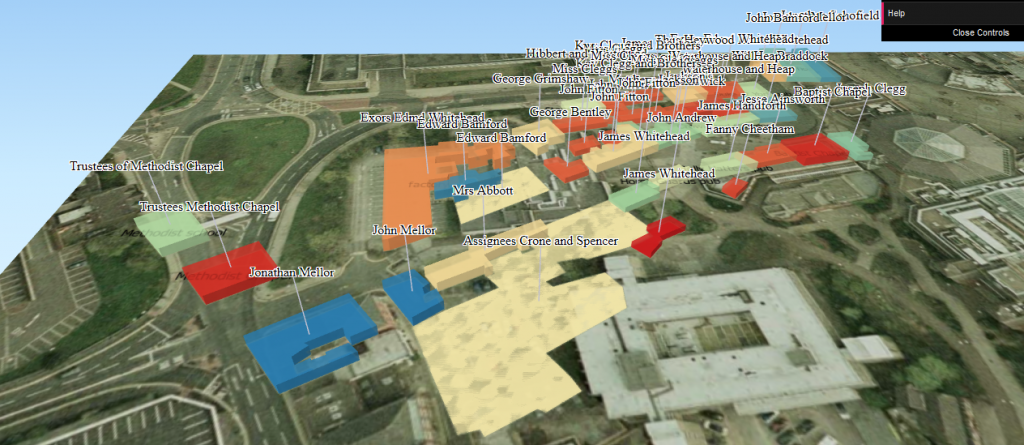

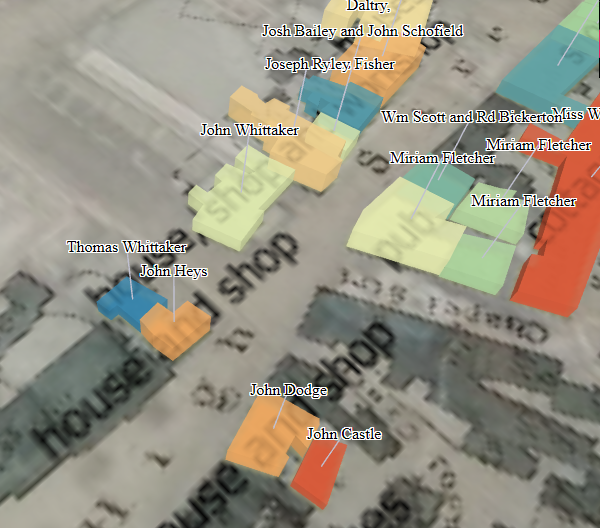

Link to a 3D model of buildings and their landowners on Dunn’s 1829 map of Oldham:

Instructions on how to navigate the map are in the ‘Help’ section. Click Ctrl + Shift and up and down keys to zoom in and out.

3D visualisation created with the three-js plugin for QGIS. Dunn’s map of Oldham landowners and occupiers is available in Oldham Local Studies, with an index.

Link to the map of landowners with Dunn’s 1829 map layered on top:

Link to timemapper timeline of Edwin Butterworth’s diaries:

Bankside Mills, 1834

The Bankside Mill trades’ agitation in Oldham showed how loitering and meeting in the streets and on moors had become explicitly political acts. On 14 April 1834, two police constables, newly appointed under the improvement act, entered the private space of the workers, that is, the trade union room in the King William IV inn. The incident sparked major rioting against both police and ‘knobstick’ spinners, culminating in an attack on the Bankside mills of the union-busting cotton manufacturer Thompson.

The riots and debate over policing were so severe that Edwin Butterworth wrote a detailed and extended narrative of ‘the most reckless and destructive outrages’. On Tuesday 15 April 1834, he reported that the whole town and neighbourhood were out, ‘vast bodies of people lined the streets all engaged in conversation upon the awful disturbances and their consequences’. The magistrates read the Riot Act and sent in the military to parade the streets. Despite this action, ‘from 2 o’clock to 5 o’clock the town continued to be filled with people discussing the news of the day, watching the operations of the military and inducing all kinds of workpeople – spinners weavers hatters colliers tailors shoemakers joiners etc – to have a general holiday’.

The next day, the combination of loitering, informal meetings, and strikes continued in an atmosphere of heterotopic holiday, mixed with an element with threat: ‘The town crowded [,] the public houses full [,] the country lanes swarming with factory lads and lasses rending the air with their frivolities and imprudence – Idleness and curiosity and loitering the order of the day’. On Saturday 19 April, Butterworth noted that the streets were no longer crowded, and he attributed this to ‘the Trade Union Committee having issued an order that all the members of their body should keep at home’.[1]

The topography of towns shaped the appearance and movement of protest. Oldham town centre has expansive views across the region, which enabled the Bankside Mill strikers to spot the oncoming arrival of troops and plan accordingly: Butterworth noted, ‘scouts it is said were placed on the tops of the mill and the rioters scampered away before they could have behold [sic] the plumes of the soldiery rising the brow from Manchester’. Notably the strikers held early morning meetings on Oldham Edge each day to plan tactics.

[1] Oldham Archives, D-BUT F/20, Butterworth diaries, April 1834.

During the Bankside mill riots, James Bentley, one of the workers, was shot. Edwin Butterworth recorded the account of his funeral in detail. On Sunday 20 April, he noted the thousands of people ‘pouring into the Town from all parts of the surrounding country for miles to attend religious worship – to render as imposing the Funeral of poor James Bentley’, and processing the three-quarters of a mile from the man’s house near Greenacres Moor to the new cemetery of Independent Providence Chapel on Regent Street.[1]

Chartist funerals continued the practice in a more elaborate and symbol-filled way, using the occasions (particularly of the funerals of Samuel Holberry and Ernest Jones but also local radical veterans including John Knight) to shape and construct the participants’ memory of the deceased’s legacy to bolster and legitimise contemporary political campaigns.[2]

[1] Oldham Archives, D-BUT F, 1834.

[2] A. Taylor, ‘Radical funerals, burial customs and political commemoration: the death and posthumous life of Ernest Jones’, Humanities Research, 10:2 (2003), 29.

You can see the originals of Edwin Butterworth’s diary entries here: Bankside Mill riots, 1834

Pubs

The Albion Inn on High Street and the Grapes Inn on Yorkshire Street were sites of continuity for political movements.

On Good Friday 1834, trade union members held a meeting at the Albion Inn to petition parliament about the Tolpuddle martyrs and on 30 December 1834, the members of the political union met there in February 1833 and 30 December 1834, though Butterworth described the attendance at the latter as ‘meagre’. Meetings to support the Ten Hours campaign were held there in February 1835 and February 1837, and radicals received John Fielden MP there in January 1837. In September 1837, a meeting of ‘shopkeepers’ heard Feargus O’Connor lecture in the inn, and the venue also hosted the committee of the working men’s association when they organized the funeral of veteran radical John Knight in September 1838. Chartists held a meeting of delegates to the National Convention there in May 1839.[1]

[1] Manchester Times, 2 March 1833; Poor Man’s Guardian, 5 April 1834; Manchester and Salford Advertiser, 30 June 1838; Oldham Archives, Butterworth diaries, D-BUT F/24, 26, 51, 56, 57; D-BUT F/4/1, 2; National Archives, HO 40/37/4/30.

The Grapes Inn was used regularly by trade unions, including the ephemeral National Union of Trades in 1830 and striking operative spinners in 1837. It also hosted the political union in November 1831, a radical dinner in celebration of radical veteran John Knight in November 1837, and the operative ultra radicals in August 1838.[1] On Good Friday 1834, trade union members held a meeting at the Albion Inn to petition parliament about the Tolpuddle martyrs. The members of the political union and the Ten Hours campaign were held at the Albion in the mid 1830s, and radicals received John Fielden MP there in January 1837. In September 1837, Feargus O’Connor addressed a meeting of shopkeepers in the pub, and the committee of the working men’s association used it to organise the funeral of veteran radical John Knight in September 1838. Chartists held a meeting of delegates to the National Convention there in May 1839. In October 1841, the Socialists opened a meeting room in Albion Inn Yard.[2]

[2] Oldham Archives, Butterworth diaries, D-BUT F/2, 3, 4, 41, 50, 53, 57.

Curzon Ground

Behind the Albion Inn was Curzon Ground. The site was also known as ‘Tommy Field’, and became the site of the market and wakes’ fairs. The landowner was Baron Curzon, later Earl Curzon-Howe, Tory lord of the bedchamber who voted against the reform bill.[3] Its sheltered but open and central position made it a chosen site, deliberately or not against Curzon, for meetings for radical reform during and after the Reform bill agitation of 1831–2. Butterworth noted in his diary that ‘the greatest meeting ever held at Oldham’ took place on Curzon Ground on Thursday 13 October 1831. The speakers took their positions on two waggons, while ‘a coach filled with spectators from Mill Bottom heightened the scene, which presented that of an immense assemblage of persons, thousands in number … greatly increased by the workpeople of many mills, which had ceased working on the occasion’.[4]

Curzon ground was also the venue for William Cobbett to address his potential new electorate in 1832, for operatives to discuss short–time working in 1833, for election hustings and demonstrations against the new Poor Law in 1837, and for Chartist meetings in 1838-9 and in the last push for the third petition in May 1848. Plug rioters met there every morning in mid–August 1842 before they set off to turn out factories and negotiate with their employers.[5] Weather was of course an issue in meeting outdoors and most of the open air meetings on Curzon Ground were held between the months of May and August.

Terrace Buildings

Many owners and landlords allowed groups of all political persuasions and memberships to rent their spaces, not least out of commercial interest. The Assembly Room in the Terrace Buildings on Church Street in Oldham, for example, was erected 1836 ‘by private enterprise’ by the druggist William Braddock. The operative conservatives held their public dinner there in January 1838, but the buildings also hosted a debate between the Methodist New Connexion and the Owenite Socialists in February 1839, temperance and science lectures and an anti-new poor law meeting in 1839, and Chartists held a meeting in the market hall to petition the Queen to recall the Welsh Chartists from transportation on Easter Monday, 20 April 1840. Yet in the same building there was a Sessions Room, used by the authorities to conduct a special petit sessions to appoint special constables during the Chartist agitation in May 1839. A meeting to consider the implications of the rural police act, attended by 200, on 2 January 1840 was followed the next day by John Fielden lecturing against the Corn Laws.[6]

[1] Oldham Archives, D-BUT F/2, 3, 4, 41, 50, 53, 57, Butterworth news reports.

[2] Manchester Times, 2 March 1833; Poor Man’s Guardian, 5 April 1834; Manchester and Salford Advertiser, 30 June 1838; Oldham Archives, D-BUT F/24, 26, 51, 56, 57, 75, Butterworth news reports; D-BUT F/4/1, 2.

[3] Lancashire RO, DP 477/1, Curzon account, 1812.

[4] Oldham Archives, D–BUT F/4, Butterworth news reports, 1831.

[5] E. Butterworth, Historical Sketches of Oldham (Oldham, 1856), pp.189, 200; Manchester Guardian, 29 June 1833, 29 May 1839; Manchester Times, 3 June 1848; Oldham Archives, D-BUT F/44, 47, 56, Butterworth news reports. The 1858 Oldham miners’ strike ended with a commemorative banquet on Tommyfield: http://www.mining-memorabilia.co.uk/OldhamMinersStrike.htm

[6] Oldham Archives, D-BUT F/53, 54, 62, 65, 67, 68, Butterworth news reports.

Links and further archives:

Oldham Historical Research group: transcriptions of William Rowbottom’s diaries: http://www.pixnet.co.uk/Oldham-hrg/archives/rowbottom/pages/000-pages-list.html

Spinning the Web site: Edwin Butterworth diaries: